On January 7, Saudi-backed forces established control over much of the former South Yemen, including Aden, its capital, reversing gains made by the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) in early December.

Meanwhile, the head of the STC, Aidarous al-Zubaidi, failed to board a flight to Riyadh for a meeting with other separatists: he seems to have fled to Somaliland and then to Abu Dhabi. The STC is a secessionist movement pushing for the former South Yemen to regain independence. The latest turn of events marks a major setback to the UAE’s regional ambitions.

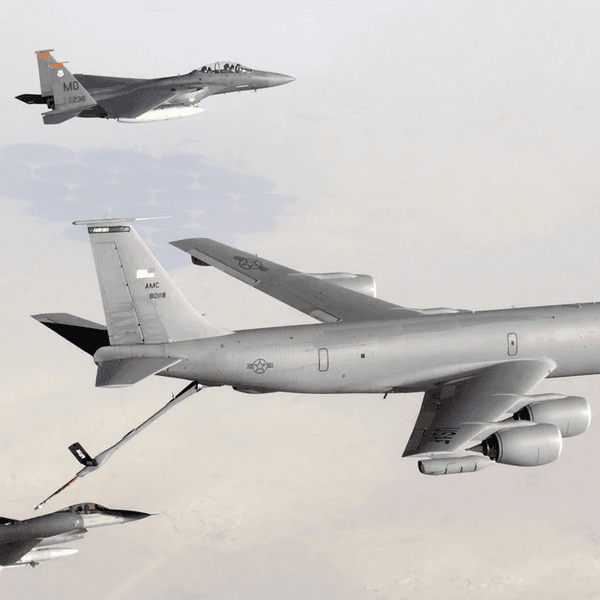

On December 30, Saudi Arabia bombed a Yemeni port to prevent an alleged Emirati weapons shipment from reaching the STC. The STC’s seizure of eastern Yemen in early December had appeared to consolidate its control over its envisioned state, a move that directly challenged Saudi authority and that of the Saudi-backed groups that oppose southern independence.

These fast-moving developments in Yemen demonstrate that Saudi Arabia will not tolerate Emirati-backed revisionism, and underscore the disconnect between Saudi and Emirati regional agendas.

Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are also pursuing incompatible outcomes across the Red Sea in Sudan where the Saudis financially support the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Emiratis provide weapons to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). The SAF have ties to the previous Islamist government of Omar al-Bashir, who was ousted in 2019, while the RSF grew out of the Janjaweed, the notorious militia that committed genocide in Darfur in the early 2000s.

The RSF, led by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, or “Hemedti,” established a parallel government in August to challenge SAF control. The violence in Sudan is driving the world’s largest humanitarian crisis, with the RSF in particular committing horrific atrocities against civilians, most notably in the city of El Fasher and elsewhere in Darfur.

In both Yemen and Sudan, the UAE supports groups that seek to fragment existing structures of state control. By backing non-state actors that undermine the security of existing states, the UAE appears to be pursuing the strategy that has earned Iran such strident criticism. What explains why the UAE would foment instability?

A significant factor in the UAE’s behavior in Yemen is to control important territory. By backing secessionist groups and other militias in Yemen, Emirati proxies until recently oversaw much of the southern coast of Yemen and islands along the strategic route. Saudi Arabia tolerated this until the STC seized territory in December along the Saudi border. That incursion, as well as the loss of al-Mahra, where Riyadh has long envisioned an oil pipeline, threatened core Saudi interests and precipitated a military response.

Another broader explanatory factor is the UAE’s opposition to Islamists. The Emirati leadership fears democratic pressure, of which political Islam, and specifically various offshoots of the Muslim Brotherhood, have been a major source.

This fear was amplified by the popular uprisings of 2011, when a group of 133 Emirati activists, academics, and lawyers — some of whom were members of the Islamist group Islah — signed a petition for democratic reforms. The government cracked down on all forms of dissent, including through mass trials, such as the UAE 94 trial in 2013, and the UAE 84 trial of 2024. Many of the original petitioners remain in prison to this day.

The Emirati leadership’s fear of political Islam has motivated its support for anti-Islamist groups in Libya, Egypt, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, and Somaliland. Turkish intelligence sources also assert that the UAE supported the failed coup against Turkey’s Islamist President Erdogan in 2016, when Ankara and Abu Dhabi supported warring sides in Libya. Qatari support for Islamist groups in the region after 2011 eventually motivated the UAE and Saudi Arabia to initiate their ultimately unsuccessful blockade of Qatar in 2017.

The eruption of armed conflict between Emirati- and Saudi-backed groups in Yemen and Sudan raises the specter of yet another serious Gulf rift, only this time between the two largest Arab economies. The leaders of both — Mohamed bin Zayed is the president of the UAE and the emir of Abu Dhabi, Mohammed bin Salman is the crown prince and de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia — were once seen as close allies, with MBZ having mentored MBS and supported his consolidation of power.

The two leaders were also allied in their offensive against the Houthi-led insurgency that devastated much of the former North Yemen.

Yet Saudi and Emirati interests have increasingly diverged, as MBS pursues the ambitious social and economic agenda of his Vision 2030, much of which competes directly with the UAE’s already well-established role as a regional hub for finance, tourism, and investment.

Although MBS has similarly assailed Islamists, blaming them for Saudi Arabia’s previously draconian interpretation of Islam, he is primarily interested in preserving regional stability, which is necessary to achieve Vision 2030’s ambitions. If partnering with Islamists in Sudan, Yemen, or elsewhere provides stability, he is prepared to do so.

Saudi monarchs once felt they had to uphold Wahhabi doctrine in order to maintain the clerics’ stamp of approval, whereas MBS’s policy of extreme repression has largely silenced those who would portray his social reforms as incompatible with Wahhabism. He appears confident that Saudi Arabia’s religious authority as the home of Mecca and Medina will prevail even as he transforms how the kingdom practices Islam. Therefore, Islamists do not pose a fundamental challenge.

The Emiratis, on the other hand, view the threat posed by Islamists as significantly greater than that of instability, such that they prefer to support anti-Islamist groups even if doing so risks provoking violence and chaos. In this, they are not unlike Israel, with which the UAE has developed an increasingly close strategic partnership, particularly since normalizing relations in 2020.

Israel also sees Islamists, and likewise democratization in the Middle East, as a possible existential threat. If Arab government policies actually reflected the will of their populations, in its view, relations would likely become much more hostile, as public opinion polls in the region have long suggested. The new government in Damascus, for example, is Islamist: Israel looks to undermine it by supporting the Druze and other separatist movements in Syria. The Netanyahu government likewise seeks regime collapse in Iran.

Like the UAE, Israel is not threatened by secessionists. Both Israel and the UAE have pursued relations with the breakaway state of Somaliland in order to gain greater access to the Red Sea: Israel last week became the first state to recognize Somaliland. Secessionists also appear to recognize this dynamic: the STC had promised that if South Yemen achieved independence, it would recognize Israel.

The UAE may believe that by working alongside Israel, Washington will give it free rein in the region. But the U.S. government generally prioritizes stability and views chaos as dangerous, a perspective shared by Saudi Arabia.

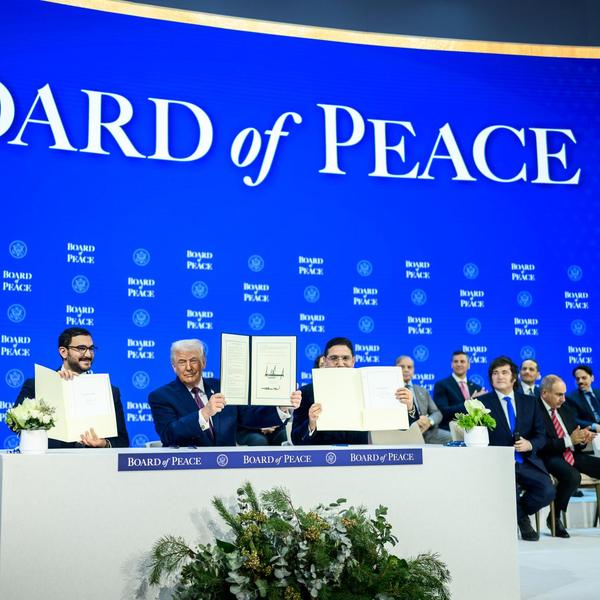

Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE are important U.S. partners; in his first trip abroad since his reelection,Trump visited both countries, along with Qatar. Open hostilities between Saudi and Emirati-backed factions in two different hot zones raise questions about how Trump will manage the increasingly fractious relationship between the two Gulf heavyweights.

On January 7, Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan visited Washington. Meanwhile, on January 5, an influential Emirati commentator seen as close to the leadership, tweeted about the situation in Yemen by acknowledging its deference, for now, to Riyadh: “The UAE realized its respected elder brother was seething with anger, and the UAE's wisdom led it to contain his anger, calm his feelings, and avoid provoking him with escalatory decisions.”

It seems that the UAE is not looking to escalate in Yemen at present, but the fundamental incompatibility between Saudi and Emirati/Israeli objectives will persist.

- Saudi leans in hard to get UAE out of Sudan civil war ›

- Saudi bombs will not thwart new UAE-linked 'South Arabia' in Yemen ›