In a recent interview, Pope Francis took stock of the war in Ukraine. “The strongest one is the one who looks at the situation, thinks about the people and has the courage of the white flag, and negotiates,” the pope told Swiss media.

The comment led to derision from Ukraine and its Western supporters, who saw in the pontiff’s message a call to capitulate. (We’ll leave aside the fact that, behind closed doors, some European diplomats are reportedly warming to the idea of a negotiated end to the war.)

Pope Francis offered an easy target for criticism by referring to a white flag, the traditional symbol of surrender. But one of his key messages actually was, “Don’t be ashamed to negotiate before things get worse.” Pope Francis has often referred to the Ukrainian people as martyrs in this war; suggestions that his words are a gift to Putin are misguided and confuse his anti-war instincts for support of Russia’s war effort.

Pope Francis noted that "the word negotiate is a courageous word.” Pierre Hazan, a senior adviser with the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue and author of a new book on conflict mediation, would probably agree. Hazan cut his teeth as a journalist covering the Bosnia War and other conflicts before putting down the pen to take an active role in armed conflict negotiations. One of these was the peace process in the Basque Country that led the terrorist group Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) to lay down its arms. In “Negotiating with the Devil: Inside the World of Armed Conflict Mediation,” the Swiss mediator mounts a strong defense of the importance of negotiation in the middle of a conflict.

Before extolling the virtues of talks, Hazan acknowledges the potential pitfalls. Among other things, negotiations risk being manipulated by one of the parties. The author provides the example of the Munich Conference in 1938, which became the antechamber of Adolf Hitler’s march on the European continent.

There is also the possibility that talks become a smokescreen for violence. Hazan mentions here the Norwegian-led mediation between the Sri Lanka government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a group of ruthless insurgents fighting for a Tamil state. When the Sri Lankan government wiped out the LTTE in a final offensive in 2009, it also killed around 40,000 civilians in the process.

On rare occasions, the problem is not that negotiations end up facilitating carnage but that there is simply no partner willing to talk. That is the case of ISIS or the extinct Shining Path in Peru, explains the Swiss mediator.

These difficulties notwithstanding, for Hazan, the key question remains whether “negotiating with war criminals—including the worst of them—might save lives.” To this, he replies that “with very few exceptions, the answer is yes, of course.” Those who mediate in armed conflicts are forced to consider possibilities that are far removed from ideals of justice in the search for the least bad option, argues Hazan.

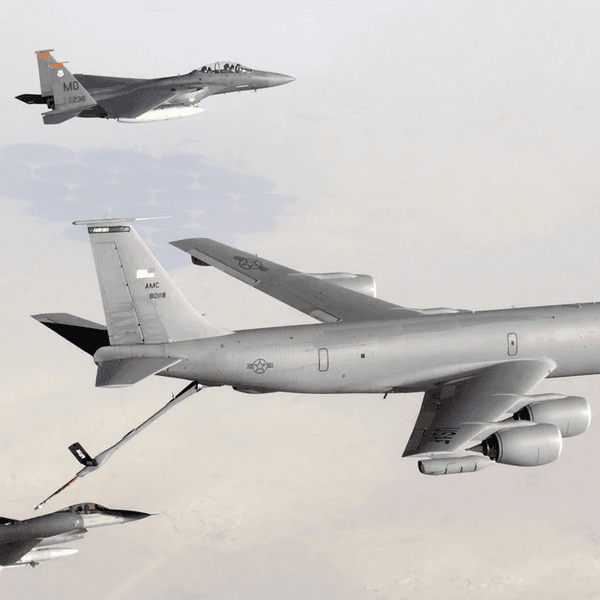

This became more complicated after the 9/11 attacks, when President Bush declared a “War on Terror,” and the room for negotiations with warring states, rebel groups, or terrorist organizations narrowed down dramatically. In this new context, remarks Hazan, “mediation, previously lauded, was pushed aside in favour of military solutions.”

If total victory over terrorists and rogue states was, as Bush suggested, both just and within reach, then there was little need for negotiation in this new world. If the goal was to export democracy and eliminate terrorism once and for all, Bush failed spectacularly on both accounts. By then, however, the world had already been defined in good-versus-evil terms. Thus, to conduct badly needed talks with the evil side of this simplistic equation (be it Iran, North Korea, or the Taliban) would have been seen as treason to our highest ideals. The U.S., with European countries often following suit, promoted a new paradigm according to which mediation was “perceived as an admission of weakness,” writes Hazan.

These dynamics can be observed in the case of former United Nations diplomat Álvaro de Soto, who resigned his position as envoy for the Middle East Peace Process in May 2007. After Hamas won the 2006 Palestinian elections, the international community halted direct funding to the Palestinian Authority. The rationale was that this would apply pressure on Hamas to recognize the state of Israel and renounce violence. The consequence was not a moderation in Hamas’ positions but a steep increase in poverty among Palestinians and a deterioration of public services.

De Soto opposed the aid blockade on Palestinians but had little room to maneuver, as the Peruvian diplomat himself explained in a secret report written before handing in his resignation. In the (subsequently leaked) report, de Soto argued U.S. pressure had "pummelled into submission" the U.N.’s role as a neutral mediator in the Middle East. As Hazan explains, one of the biggest obstacles for de Soto was that his superiors forbade him to continue talks with Hamas or the Syrian government.

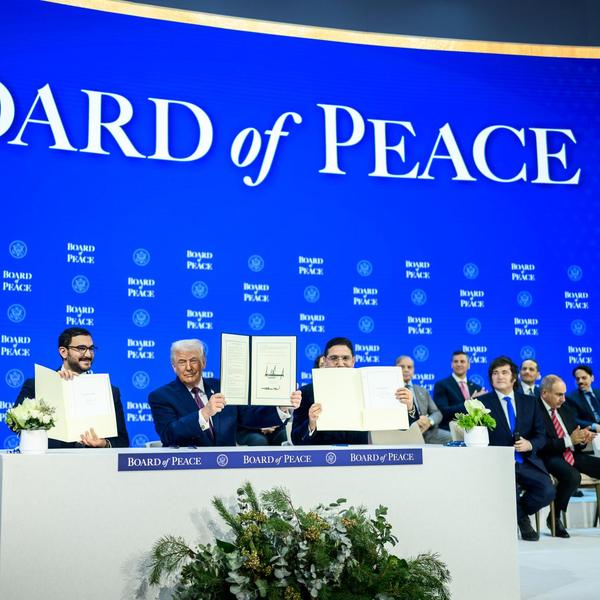

Hazan added a preface to the original French edition of his book to cover the events that followed Hamas’ attack against Israel on October 7, when the militant group killed 1,200 people and took 240 hostages. Since then, Israel’s military operation in the Gaza Strip has resulted in the death of at least 31,000 people. Hazan reflects on the Qatar-mediated ceasefire in Gaza that lasted for a week at the end of November 2023. The ceasefire, the author argues, was a historical development for at least two reasons. First, it was probably an unprecedented agreement, as hostages were directly exchanged for ceasefire days. And second, Qatar’s role exemplified “the end of Western hegemony over the international system.”

Whether Western hegemony will be followed by something better is up for debate. However, when Hazan points to Turkey’s role in the mediation of the grain deal between Russia and Ukraine, or to China’s diplomatic efforts leading to the resumption of ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia, it is easy to recognize a pattern towards a broader plurality in the mediation scene.

Hazan offered an interview last month discussing the latest developments in the Ukraine war, which are not included in the book. Hazan explained that he sees two main scenarios for a mediated solution in Ukraine. In the first one, a precarious calm would prevail and there would be a limited ceasefire with Russia and Ukraine technically at war for the foreseeable future. In the second one, what he calls the “Korean model,” there would be a demilitarized zone between the two sides with Ukraine obtaining security guarantees and NATO/European Union membership. A more robust mediation process and peace agreement will only happen “if the military or the political situation changes radically either way,” he argued.

Based on his long-time experience, Hazan notes that “peace is a messy, chaotic business, as is the road that leads to it.” There is no sense in negotiating only for negotiations’ sake, and mediation is fraught with dangers.

Yet experts should not be swayed by the supposed moral certitude of refusing to come to the table. Outright negation of the possibility of talks carries the risk of missing opportunities to settle for the lesser evil even as the greater good fades into the distance.