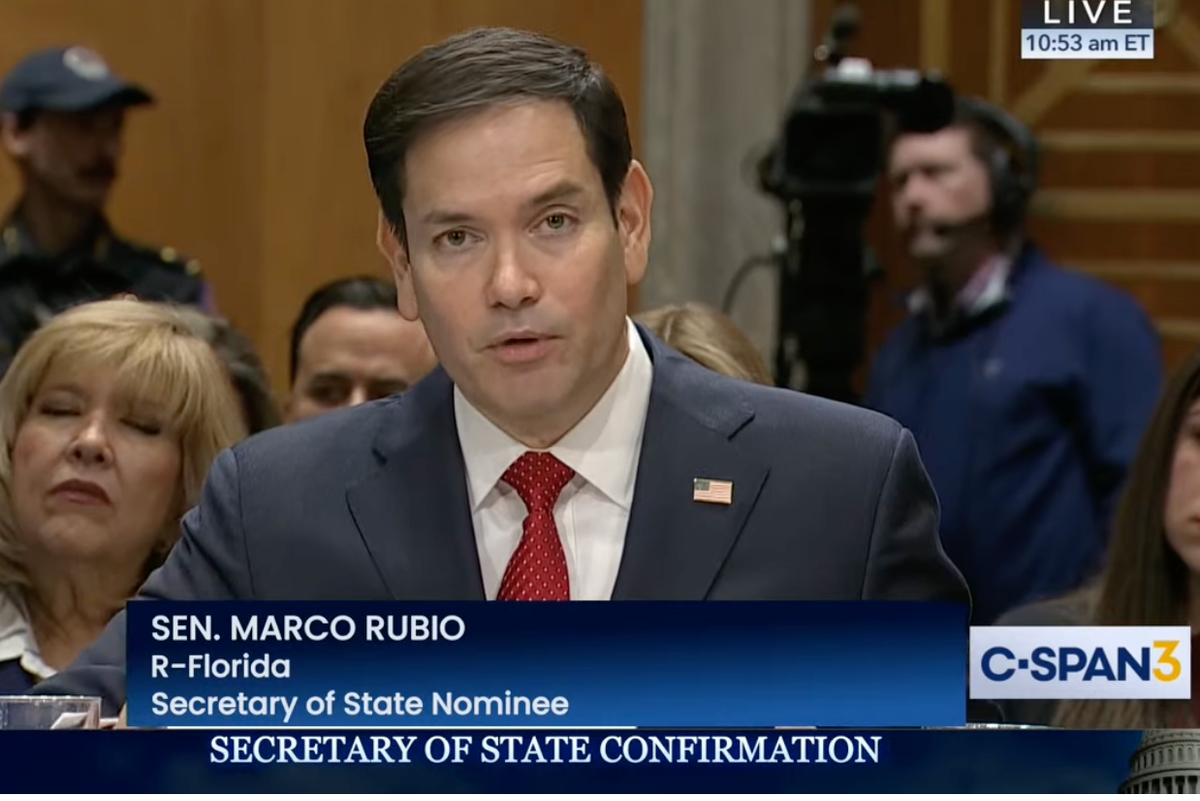

At his Senate confirmation hearing for secretary of state on Wednesday morning, Florida GOP Senator Marco Rubio called for an end to the war in Ukraine, including possible Ukrainian concessions to Russia.

Reflecting the views of his soon-to-be Commander in Chief Donald Trump, the Florida senator has become increasingly critical of the nearly three-year-long conflict in Ukraine, voting against a $95 billion Ukraine aid package in April of last year.

“I think it should be the official position of the United States that this war should be brought to an end,” Rubio said, while emphasizing the conflict’s collateral damages for Ukrainians. “The destruction that Ukraine is undergoing is extraordinary. It’s going to take a generation to rebuild it.,” he said.

“Millions of Ukrainians no longer live in Ukraine…how many of them are going to come back, and what are they going to come back to?” Rubio asked, noting that Ukraine’s infrastructure, especially energy infrastructure, has been decimated.

“The problem with Ukraine is not that they’re running out of money, but that they’re running out of people.”

Achieving an end to the war will not “be an easy endeavor… but it's going to require bold diplomacy, and my hope is that it can begin with some ceasefire,” Rubio said. “It’s important for everyone to be realistic: there will have to be concessions made by the Russian Federation, but also by Ukrainians.”

Interestingly, Trump national security adviser pick Mike Waltz recently pushed for the Ukrainian draft age to be lowered from 26 to 18, arguing Ukraine must be “all in for democracy.”

But if he was emphasizing peace in Eastern Europe, Rubio was pushing something altogether different with China, calling “the Communist Party of China…the most potent and dangerous near peer adversary the United States has ever confronted.”

“We have to rebuild our domestic industrial capacity” to counter China, Rubio claimed. “If we don't change course, we are going to live in a world where much of what matters to us on a daily basis, from our security to our health, will be dependent on whether the Chinese allow us to have it or not.”

- With Rubio, Waltz, a harder line on Latin America looms ›

- How can the war in Ukraine end? Let's count the ways. ›

- Diplomacy Watch: Here comes Trump | Responsible Statecraft ›

- What Rubio said about multipolarity should get more attention | Responsible Statecraft ›