Toxic exposure during military service rarely behaves like a battlefield injury.

It does not arrive with a single moment of trauma or a clear line between cause and effect. Instead, it accumulates quietly over years. By the time symptoms appear, many veterans have already changed duty stations, left the military, moved across state lines, or lost access to the documents that might have made those connections easier to prove.

For decades, this gap between exposure and recognition has defined the experience of many veterans. Illness emerges long after service, while the places where that exposure occurred fade into memory or paperwork archived beyond reach. In the absence of clear acknowledgment, veterans are often left to reconstruct their own histories, searching for evidence that what happened to them was not coincidence.

Today, many veterans rely on public environmental data to fill those gaps. State water testing results, federal cleanup records, Environmental Protection Agency databases, and installation level assessments have become critical sources for understanding what was present in the air, soil, and groundwater at military bases. These records help bridge the distance between lived experience and the official record. Yet for most veterans, the information remains scattered across agencies, buried in technical documents, and difficult to interpret without specialized knowledge.

That fragmentation has long been a barrier to accountability.

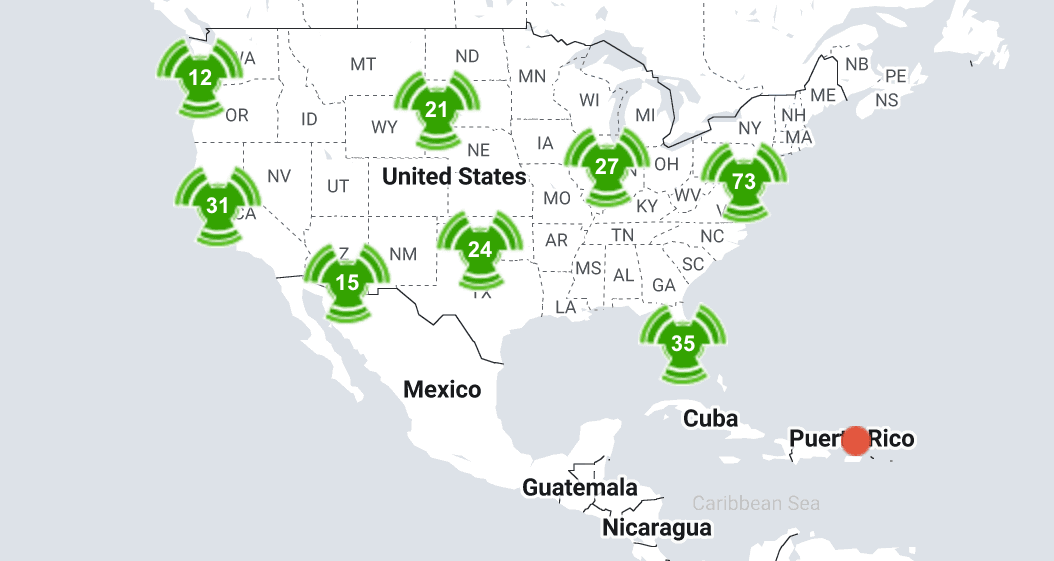

This is why our firm, Hill & Ponton, developed the Military Base Toxic Exposure Map. The tool aggregates publicly available environmental data tied to hundreds of military installations across the United States and abroad, placing it into a single, searchable platform. Veterans can look up bases by name or state and see whether documented contamination has been recorded at locations where they served.

The map draws on existing public sources, including base cleanup histories, PFAS detection reports, groundwater monitoring data, and environmental assessments. It does not speculate or create new findings. Instead, it organizes what is already known and makes it accessible to people who have the most at stake in understanding it.

In that sense, the toxic exposure map follows a familiar model. Hill & Ponton previously developed a Blue Water Navy ship position map used by veterans seeking recognition for Agent Orange exposure. That earlier tool allowed sailors to verify whether their ships entered waters known to be contaminated, using declassified ship logs and official records. The new mapping effort applies the same principle to land based service, allowing veterans to locate installations where they served and see whether those sites have documented environmental hazards.

What these maps provide is not a diagnosis or a legal conclusion. They provide transparency. For many veterans, transparency is what has been missing for years.

Environmental exposure on military bases has often been treated as an administrative problem rather than a policy failure. Contaminated water systems, industrial solvents used in maintenance operations, fuel spills, and open burn practices were frequently normalized as part of military life. Oversight lagged. Monitoring was inconsistent. Records were incomplete. When contamination later came to light, responsibility was diffused across agencies and decades.

The consequences of that approach did not disappear when service members left the military.

Although the PACT Act expanded benefits and presumptive coverage for some toxic exposed veterans, many cases involving base contamination still fall outside those categories. Veterans who served decades ago, rotated through multiple installations, or developed conditions not yet formally recognized must still prove where they served and how those exposures relate to their current health. Without accessible documentation, that burden can feel insurmountable.

Mapping does not solve that problem on its own. But it changes the starting point.

By consolidating environmental data tied to specific locations and timeframes, the toxic exposure map allows veterans to bring concrete information into conversations with healthcare providers and the Department of Veterans Affairs. It helps establish exposure timelines and grounds claims in documented environmental conditions rather than memory alone.

This is not a question of expanding benefits indiscriminately. It is a question of aligning policy with reality.

The United States maintains one of the largest military infrastructures in the world. That footprint includes environmental consequences that do not end when a base closes or a service member discharges. Ignoring those consequences shifts long term costs onto veterans and their families, while eroding trust in the institutions responsible for their care.

Mapping toxic exposure is a modest step, but an essential one. It acknowledges that environmental harm leaves records, even when recognition lags behind. It gives veterans a way to see whether the places they served have documented histories of contamination and to ask informed questions about their health.

Most importantly, it reframes toxic exposure not as an unfortunate anomaly, but as a governance issue with lasting human consequences. Veterans upheld their obligations in service. Transparency and accountability after service should not be optional

- Military slammed by new mold revelations in military housing ›

- Left behind, Afghanistan is now an environmental hellhole ›

- DOD has money for boondoggles but not clean water for bases? ›