Mexico and Chile’s recent referral to the International Criminal Court (ICC) for an investigation on crimes against civilians in Gaza during the current Israeli campaign (and the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks inIsrael) is another sign of increasing support in the Global South for an international legal route against the ongoing war and siege of Gaza.

The question of whether Israeli troops are committing war crimes in a continuing and devastating war has been met with deep resistance and anger in Israel and among its supporters in the United States. As the core backer of Israel’s war, there are reputational implications for the United States here, too.

Several developing countries have explicitly come out in support of South Africa’s case (or “application”) against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in late December 2023 on the even more serious charge of genocide, while others have done so indirectly, as a part of resolutions passed by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and the Arab League.

And in November, South Africa, Bolivia, Bangladesh, Comoros, and Djibouti made their own referral to the ICC on possible crimes committed against Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza strip.

There is also another case making its way through the ICJ on an advisory opinion “in respect of the Legal Consequences arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem.” The case is the outcome of a UN General Assembly resolution asking for such an opinion adopted on December 30, 2022. Indonesia has recently announced that the foreign minister herself, Retno Marsudi, will fly to the Hague to make oral arguments backing Palestine in this case.

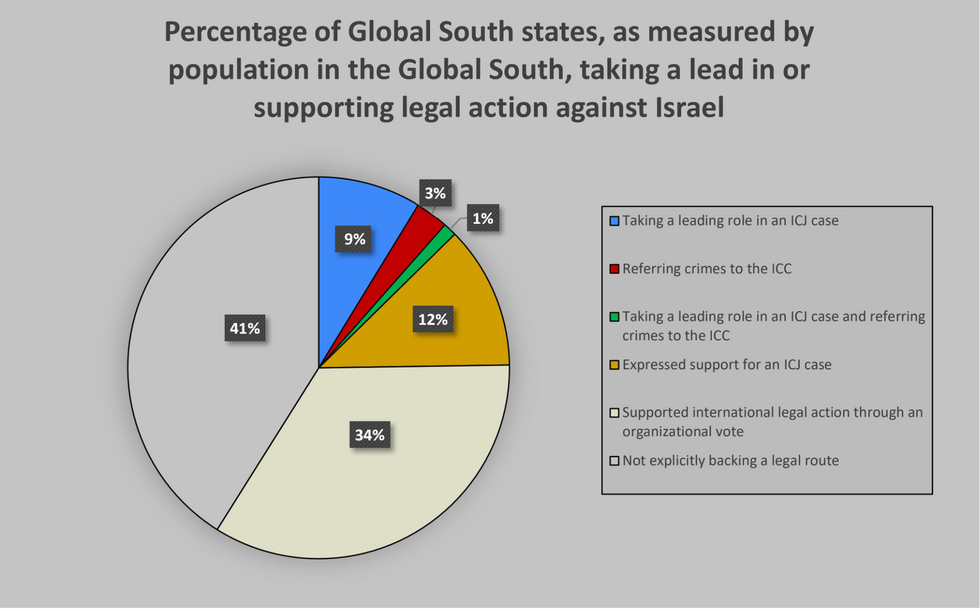

Mapping the increasing recourse to international legal action by Global South states against Israel’s actions in Palestine is revealing, indicating that time does not seem to be on Israel’s side when it comes to winning friends in this space. States either leading or supporting such actions span across almost all of the Global South, including Latin America, Africa, West Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. And the actions initiated by South Africa, Mexico, and Chile, and the wide support for the UNGA resolution of December 2022, shows that this sentiment extends well beyond Arab or Muslim-majority states.

When tallied by the populations of these states, about 59% of the Global South has now led or backed international legal action against Israel. Moreover, as our mapping of the UNGA resolution of December 12 showed, a vast majority of Global South states have gone on record supporting an unconditional humanitarian ceasefire in Gaza.