Reading a book in which you essentially follow bread crumbs to a seminal historical event, it’s easy to spot the neon signs signaling pending doom. There are plenty of “should have seen that coming!” and “what were they thinking?” moments as one glides through the months and years from a safe distance. That hindsight is absurdly comforting in a way, knowing there is an order to things, even failure.

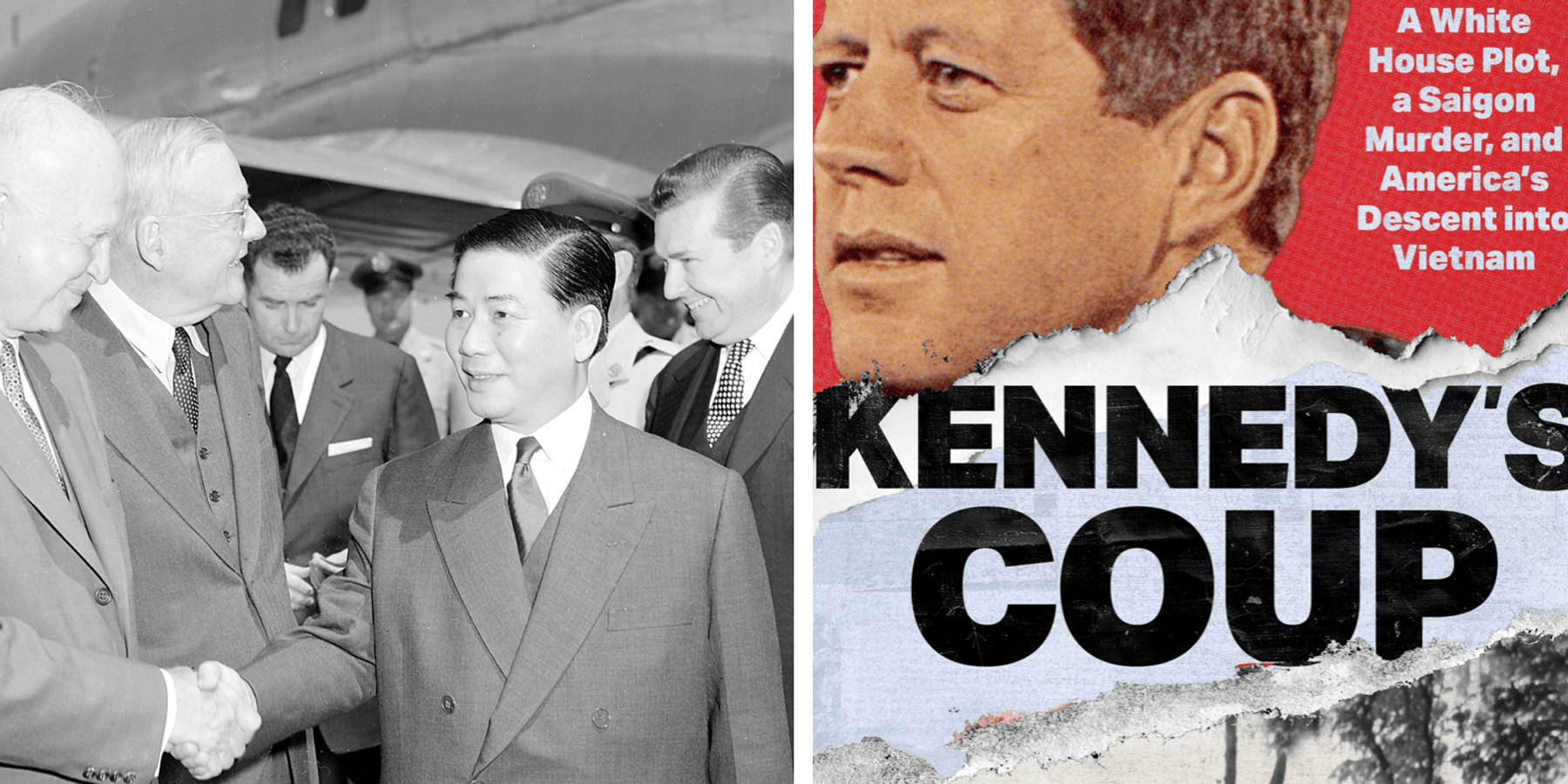

But reading Jack Cheevers' brand new “Kennedy’s Coup: A White House Plot, a Saigon Murder, and America's Descent into Vietnam” just as the Trump administration is overthrowing President Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela is hardly comforting. Hindsight’s great if used correctly. But the zeal for regime change as a tool for advancing U.S. interests is a persistent little worm burrowed in the belly of American foreign policy, and no consequence — certainly not the Vietnam War, which killed more than 58,000 U.S. service members and millions of Vietnamese civilians before ending in failure for our side — is going to stop Washington from trying again, and again.

Assiduously compiled from new material gleaned through Freedom of Information (FOIA) requests and recently declassified documents and years of research and interviews, Cheevers' book is an exhaustive history of the period just before the U.S. officially went to war in Vietnam in 1965. During this time, beginning in the mid-1950's (following Vietnam’s independence from the French), Washington was deploying military advisors (and lots of hardware) via Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) to work with the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) against the communist North Vietnamese-backed Viet Cong in South Vietnam.

At the center of this story is Ngô Đình Diệm, the independence leader turned head of the new South Vietnamese republic. He is from an old and noble Catholic family subordinated by French rule but powerful enough in stature and wealth to pursue a nationalist rebellion first against the French, and then the Vietnamese mafia running Saigon. He is complex, enigmatic, at times sympathetic, other times frustratingly tedious and unaware. His relations with the growingly powerful Buddhists are tense and become a major aggravating factor in his demise.

We are brought into the “present” in 1960. As Diem, along with his right hand political advisor/brother Nhu and Nhu’s wife Madame “dragon lady” Nhu become increasingly isolated and despotic, we are introduced to a cast of American characters who will play some role in the advancing the Nov. 2, 1963 coup and assassination of Diem and Nhu — either as active participants in the conspiracy, or as the skeptics, more understanding of Diem’s position and concerned that he was the only one keeping the restive political factions in Vietnam together. The latter included U.S. Ambassador “Fritz” Nolting, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Maxwell Taylor, and General Paul D. Harkins, who was commanding MACV at the time.

The active participants consisted of, but certainly were not limited to, U.S. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., who replaced Nolting in 1963, CIA agent Lucien Conein, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, and Roger Hillsman, foreign policy advisor to President Kennedy and drafter of the now infamous “Green Light Memo,” dated August 24, 1963. This memo made it official that the U.S. was prepared to support Diem’s generals in a coup if Diem did not accede to Washington’s stated demands, primarily, that he toss his brother Nhu aside.

Cheevers also charts the contributions of the American press corps in Saigon, a fascinating orbit of outsized personalities like David Halberstam, Peter Arnett, and Neil Sheehan, who were ambitious and indefatigable, if not at times self-righteous and rigid in their commitment to reporting the flailing ARVN operations against the Viet Cong (and to the idea that the Kennedy people and U.S military brass were sugarcoating it). Unlike today, these reporters were able to hitch rides with lower ranking military officers on helicopters and spend time with American units and soldiers who spoke freely from the battlefield. They also crossed swords with Diem’s supporters in the American diplomatic corps, which thought the men were sensationalizing the Buddhist monk protests (many were self-immolating in the streets during this time) and over-dramatizing Diem’s crackdowns and the weakening state of his rule to sell papers.

Ironically, their reporting helped Lodge, Hilsman & Co. build a political case for a coup and led to a souring on Diem back home, but did not ultimately stop an expansion of the war.

Then there is Jack Kennedy, who appears thoughtful but indecisive to a fault, who conducts national security meetings like socratic seminars leaving most participants either failing to be heard, bullied by the bigger personalities in the room, or left not knowing where the president really stands. Kennedy is the American tragic figure here. From all accounts he was badly shaken by Diem’s killing — somehow he was assured it wouldn’t happen — and makes some of the most chilling statements in the book afterward, telling pro-coup advisor Michael Forrestal that he wanted a “profound review” of the U.S. in Vietnam and “whether or not we should be there.” He also reportedly told close confidant and White House appointments secretary Kenneth O’Donnell that he wanted a landslide victory in 1964, which would give him the political capital to pull U.S. troops out of the war. Days later on November 22, 1963, he lay dead, assassinated in Dallas.

As Cheevers, a career journalist who worked for the Los Angeles Times for years before retiring to become a historical writer, points out, the coup was the catalyst for what we now know as the Vietnam War. No one knew quite how to replace Diem — as dysfunctional, corrupt and despotic as he was — in order to rebuild a better, more democratic system. Coup promoters like Lodge fled like rats off a sinking ship if not physically but mentally. Lodge, who remained working for the successor Johnson administration, seemed “puzzled” and “remote” when the junta asked the Americans for help. In fact, as Cheevers points out, he was more interested in pursuing his own presidential run in 1964.

There were two more military putsches after 1963. The battlefield situation deteriorated badly. The VC was “seizing the initiative” in key provinces and their attacks became more brazen. President Lyndon Johnson appeared to have the same aversion to quagmire as his predecessor, but soon found himself in the same position as Kennedy when the VC started targeting U.S. military in the region in 1964 and the pressure was on to attack North Vietnam in a major strategic bombing campaign. Operation Rolling Thunder was launched in March 1965 and tens of thousands of young Americans were called up for deployment into Vietnam, sealing Johnson’s own political fate. The rest is history.

The obvious lesson — “be careful for what you wish for” — is an oft-used argument against U.S. regime change fantasies today. It is rarely heeded. But what Cheevers presents here is much more nuanced and critical to our understanding of what happened. Diem’s supporters in Saigon, like Nolting and Taylor and Harkins, were willing to ignore or minimize the VC’s growing superiority on the battlefield and Diem’s weakening position because they wanted the U.S. to stay, they believed the domino theory and that America was there to do good. Those pushing the putsch were myopically anti-communist too, they thought replacing Diem would help win the war against the North and prevent a communist sweep regionally. Many of these people, from both camps, went on to convince Johnson — Robert McNamara, Maxwell Taylor, William Bundy, etc. — that the war needed to be expanded.

There was no one looking at withdrawal. “Nuetralization” — an idea pressed for years by France’s Charles de Gaulle that would, through intense negotiation, hammer out a deal in which both North and South would commit to no outside military alliances in service of a future reunification — was roundly discarded by both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. Thirty years later McNamara admitted “we erred seriously in not even exploring the neutralization option.”

Twenty years after Iraq, Washington’s policy establishmentarians offer up such musings on that war too. Cheevers' immense contribution here is to show how power dynamics in war work, how the Cold War mentality ate the brains of our best and brightest and then ate our memories too, as we skipped like eager school children into another regime change war in 2003. Who are the McNamaras, Hilsmans, Taylors, Lodges and Bundys today? What new fresh hell will they deliver up next? We can only look at the present power dynamics and hope someone is heeding the neon signs on the inside.

Join RS's Kelley Vlahos, author Jack Cheevers, and Cold War researcher Arturo Jiminez-Bacardi in a special webinar to discuss "Kennedy's Coup" and its imprint on US foreign policy, on Tuesday Feb. 17 at 1 p.m., link here.