The U.S.-China relationship has emerged from one of its lowest points in decades and successfully entered a new, albeit cautious and uncertain, phase of renewed dialogue and cooperation, verging on a delicate detente.

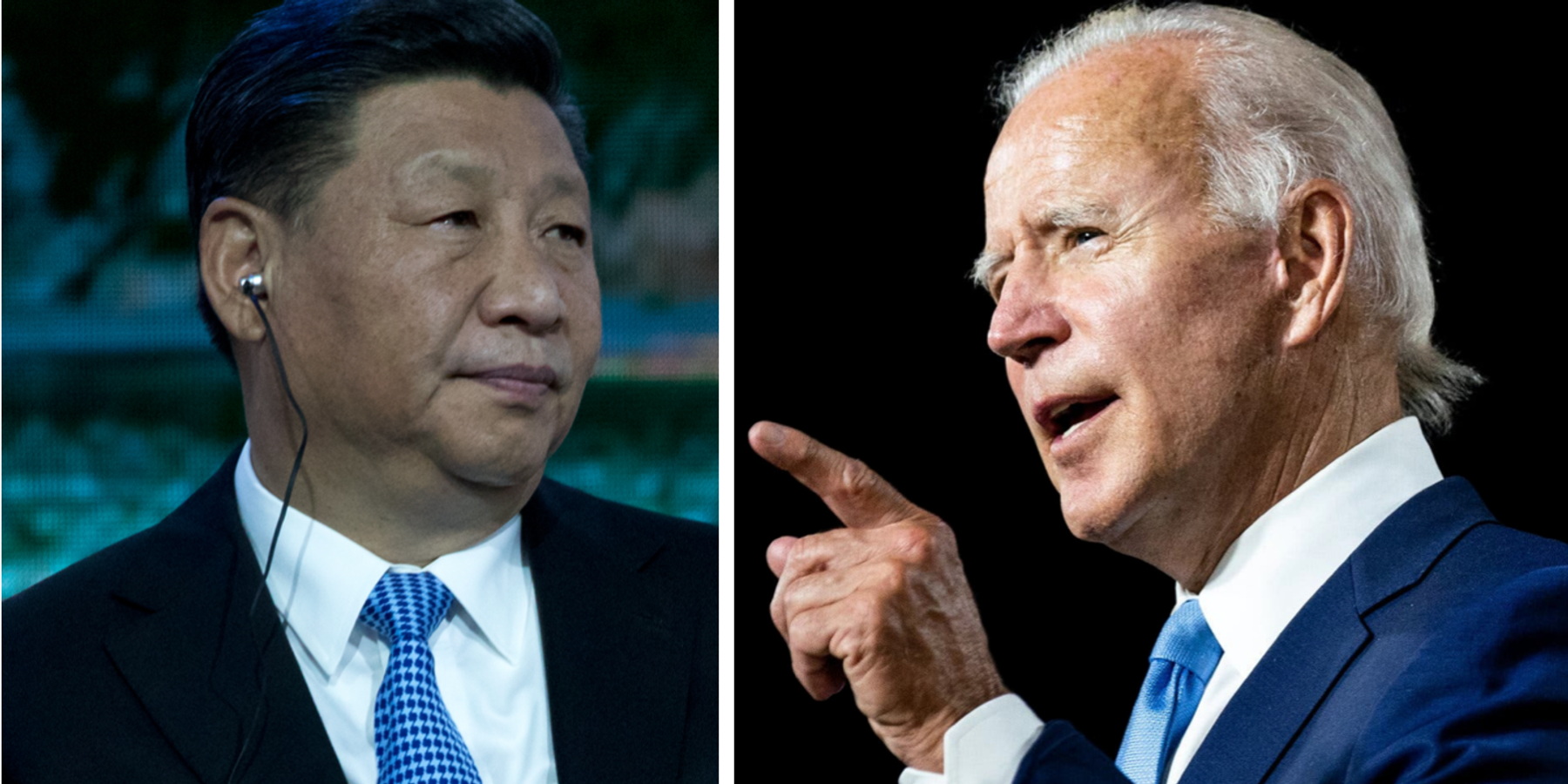

Months of high-level meetings and diplomatic signaling have paved the way for a summit between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping in San Francisco tomorrow, marking Xi’s first visit to the United States since 2017. Among the substantive agreements the two may reportedly announce are a pledge limiting the use of artificial intelligence in nuclear command and control systems as well as autonomous weapons such as drones, and a deal to limit the flow of fentanyl from China to the United States.

Even absent such agreements, the summit broadly represents an affirmation of the Biden administration’s approach to China: “intense diplomacy” is possible amid “intense competition.” But it also exposes this approach’s fatal flaw: managing tensions through dialogue will, in the long run, not be enough.

Sustainable peace and stability ultimately requires getting at the root causes of those tensions, and must be built upon a foundation of genuine negotiation and compromise to slow down the escalating military competition and arms race between the two countries. Washington has yet to wake up.

To start, this is a detente deferred. The Biden-Xi summit comes nearly a year to the day since the two met in Bali, Indonesia, seeking to mend the rupture caused by then-Speaker Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan last August, and laying the groundwork for wide-ranging diplomatic engagement in the months ahead. This was to include a trip by Secretary of State Antony Blinken to China in February, the first by a member of Biden’s Cabinet, but that was canceled amid the diplomatic fallout over the Chinese spy balloon. The relationship came to a sudden, grinding halt, but channels gradually reopened in the subsequent months, driven in no small part by China’s own economic woes.

The two sides now have a chance for redemption. A sign that this time is different would be Xi agreeing to Biden’s longstanding request to reopen military-to-military channels that were shuttered following Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan and have remained closed. If the summit produces this or other tangible outcomes, and contributes to a sustained lowering of tensions and further rounds of high-level dialogue, this would represent a powerful affirmation of the Biden administration’s overall approach to China from the beginning.

In its first few years, the administration spoke of placing the United States in a “position of strength,” by repairing and revitalizing its alliance system, coordinating with those allies to increase economic and geopolitical pressure on China, and “getting our own house in order” by overcoming the Covid-19 pandemic and implementing economic and political reform at home.

From this position of strength, the administration then moved toward creating a new status quo in the relationship, setting new terms and norms that would mark a clear and final departure from the decades-long era of “engagement” and the true start of the era of “competition.” Whereas Trump took a sledgehammer to the foundations of engagement, Biden has sought to build a comprehensive and coherent approach out of the rubble, one designed to last for the decades ahead.

The “new terms” of the relationship are that the United States and its allies will adopt aggressive, and sometimes unprecedented, military, economic, and diplomatic policies to secure their interests, but that dialogue and cooperation on common challenges would continue for their own sake, and in fact would serve as a release valve for the tensions and pressures of competition.

Speaking on background to the press, a senior White House official stressed that “our China policy has not changed.” Indeed, the Biden-Xi summit represents the logical evolution and maturation of the administration’s approach, exemplifying what “responsible competition” means in practice. “Intense competition requires and demands intense diplomacy to manage tensions and to prevent competition from verging into conflict or confrontation,” the official said.

A key pillar of “intense diplomacy” is “guardrails,” particularly military-to-military dialogue and crisis management mechanisms meant to ensure that aggressive maneuvers from both sides do not cause an accident that inadvertently sparks a crisis which metastasizes into a wider war neither seeks.

This is where the Biden administration’s vision goes wrong. Even if there is a re-opening of some military channels, Beijing has a history of not picking up the phone. In its view, “guardrails” of this sort serve as a source of moral hazard, creating a safety net that only incentivizes and encourages the United States to engage in military activities that Beijing sees as anathema to its interests, security, and prestige.

Throughout the current thaw, Beijing has demonstrated its conviction to maintain an assertive military posture, instigating tensions with the Philippines in the South China Sea, threatening Taiwan with a record number of aircraft incursions, and repeatedly harassing U.S. and allied forces conducting patrols in the region. Last month, the Pentagon declassified evidence demonstrating that the PLA Air Force had engaged in more “coercive and risky” actions over the past two years than in the entire decade prior.

At a CSIS event last week, Congressman Raja Krishnamoorthi, ranking member of the House Select Committee on China, asked matter-of-factly: “Wouldn’t it make more sense for us to open a military-to-military communications channel right now, when just the other day, a bomber, one of our bombers, was approached within 10 feet by a J-11 fighter of the People’s Liberation Army, and almost had a collision? Imagine what would have happened if there’s a fatality.”

This question reflects either a basic misunderstanding of the strategic dynamics between the two sides, or a deliberate, willful ignorance: for Beijing, the risk and uncertainty is the point.

As the Stimson Center’s Yun Sun wrote in July, “Beijing thinks that such dialogue serves as a guardrail or a safety net that allows the United States to keep conducting military activity in the western Pacific without fear of repercussions,” and that answering crisis hotlines is “a sign of weaknesses and an indication that it is willing to deescalate, which defeats the entire purpose of brinkmanship.”

“Beijing wants Washington to worry about China’s provocative military acts, to ask for reassurance, and then not receive it,” Sun continued. “Ultimately, to manage crises and prevent conflict, China believes the United States must stop talking and start eliminating what Beijing sees as the source of tension: Washington’s presence in the western Pacific.”

The Biden-Xi summit is, of course, an unmitigated good. But the Biden administration’s China policy will ultimately have amounted to a tragic failure, for it has failed to grapple with the fundamental contradiction at the heart of the relationship: the United States’ primary tool for maintaining the status quo and responding to military tensions with China — military power, pressure, and deterrence — is, from Beijing’s perspective, the underlying structural cause of those tensions.

Sun further observes that “within China, there is an increasingly popular (if fatalistic) view that a military crisis may be inevitable, and perhaps even desirable,” as “Beijing and Washington need to reach an impasse akin to the Cuban missile crisis of 1962… before they can sit down and negotiate the terms of their coexistence,” including establishing “ground rules the United States will follow when operating in China’s periphery.”

Unfortunately, history is likely to remember Biden as the president who only set the stage for the crisis that eventually forced such a reckoning, rather than the one who had the political courage, strategic foresight, and diplomatic acumen to face down this reckoning himself.

- The US is making a very big deal over Chinese 'interceptions'. Why? ›

- Lots of talking produced Xi-Biden meeting. Now, action? ›