The election of Bola Tinubu as Nigeria’s new president offers a minimal window for the United States to pursue a more dynamic relationship with Nigeria. But Washington should not delude itself: the prospects for deep reform under Tinubu are slim, including when it comes to Nigeria’s grim human rights record.

U.S. engagement with Nigeria has long emphasized security, democracy, and the economy, but on each of those fronts there is limited hope for progress currently and in the medium term. The most serious opening lies in attempting to convince Tinubu to reassert Nigeria’s diplomatic leadership in West African affairs.

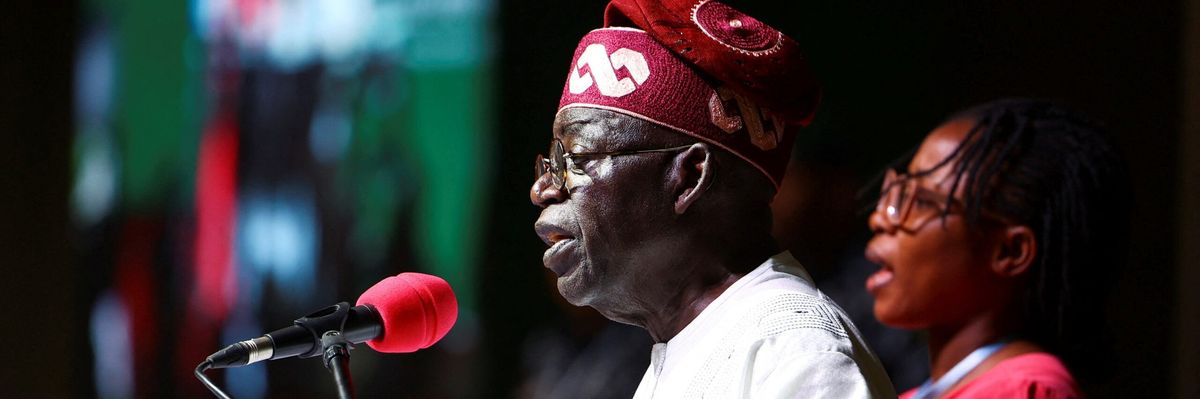

Nigeria held its elections on February 25, and Tinubu — the ruling party’s candidate — was declared the winner on March 1. Tinubu has won the election under a cloud: violence, intimidation, and delays marred the voting, and the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) has been severely and justifiably criticized by Nigerians and international voices for its messy and opaque tabulation process. Flawed elections have occurred before in Nigeria, but this year’s problems stand out even more starkly because this election featured unprecedented levels of support for a third-party candidate, Peter Obi.

Obi became the bearer of hopes for many youth as well as for many reform-minded, business-oriented citizens; tellingly, he just barely won Nigeria’s most populous state and commercial epicenter Lagos, according to official results, and his actual margin there may have been far higher. Obi’s candidacy was always a long-shot, and it is doubtful that his presidency would have lived up to the hype. Obi’s political career prior to his self-reinvention in 2022 was quite conventional. Yet hopes were high, and the ensuing disappointment and anger are profound.

Amid the opposition’s allegations that the ruling party and INEC were rigging the election on behalf of Tinubu, who is the first candidate since 1983 to win a Nigerian presidential election with less than 50 percent of the vote. Obi is heading to the courts to mount a challenge, although precedent (at least at the presidential level) suggests that legal challenges have little chance of overturning the results.

Assuming the results hold, Tinubu will take office in May and succeed Muhammadu Buhari, a former military ruler-turned-two-term president. Buhari came into office in 2015 as the bearer of high hopes when it came to reversing insecurity and tackling corruption. The United States invested considerable diplomatic capital into the effort to ensure a clean and fair election in 2015, with senior Obama administration officials speaking publicly and privately in the runup to that contest.

U.S. diplomacy perhaps played some role in what turned out to be a widely lauded election and the first (and so far only) electoral transfer of power from one party to another in Nigerian presidential history. Yet since then, the U.S. and the U.K. have retreated somewhat from prioritizing democratization, instead emphasizing security cooperation. Eight years later, Buhari is leaving behind a country that is worse off in almost every respect. Recurring violence now afflicts many parts of Nigeria, inflation is roaring, and policymaking appears disconnected from ordinary people’s realities — a recent rollout of new banknotes, for example, has caused chaos and hardship.

U.S.-Nigeria relations have been functional in the past decade but seldom warm. Nigerian leaders do not want to be lectured or condescended to — and understandably so, given Nigeria’s vast population, resources, and regional importance. U.S. policymakers have struggled, meanwhile, to balance priorities for Nigeria, realizing that they cannot ignore sub-Saharan Africa’s most populous nation but often feeling that Nigeria is underperforming economically, militarily, and diplomatically.

Security assistance has been a key source of dilemmas for the United States, particularly when it comes to Nigeria’s struggle with Boko Haram and its offshoots. Ultimately, as a recent Reuters investigation found, the U.S. (and the United Kingdom) have prioritized continued counterterrorism cooperation and military assistance over human rights concerns.

This is the wrong approach; under the past several Nigerian administrations, U.S. military assistance and sales yielded no meaningful influence over Nigeria’s brutal and largely unsuccessful campaign to stamp out various domestic insurgencies. As part of its investigation, for example, Reuters revealed a campaign of forced abortions inflicted by the military upon women who had lived under Boko Haram rule; these abortions took place on a wide scale under both Buhari and his predecessor, Goodluck Jonathan. Abuses proceed with the knowledge, and seemingly the encouragement, of an array of military and civilian authorities, regardless of who holds the presidency.

From 2017 through early 2022, Nigeria purchased roughly $500 million in hardware and services under the U.S.’ Foreign Military Sales program, while the U.S. provided some $150 million in “train and equip” programs — essentially treating Nigeria as a customer. Such assistance can always be justified in Washington by invoking the specter that competitors such as Russia and China will step into fill any vacuum left by the U.S., but in practice the U.S. directly abets an abusive, deeply entrenched, and counterproductive security culture in Nigeria. The U.S. should pull back on sales and assistance, recognize its limited influence over Nigeria, and instead think creatively about potential partnerships.

If Tinubu’s election offers an opportunity for Washington, it lies first and foremost in convincing Nigeria to reinvigorate its role in West African diplomacy. Not far from Nigeria are two of the region’s worst conflict hotspots, Mali and Burkina Faso — both of them under military rule, and both navigating shaky transitions before scheduled elections in 2024. Nigeria, as the seat of an important bloc called the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), has already been involved in the effort to persuade military juntas to return power to civilians, and former President Jonathan is ECOWAS’s mediator for Mali.

Yet ECOWAS has had limited leverage over the juntas, and there is a strong possibility that, particularly in Mali, military authorities will find pretexts for prolonging their rule beyond 2024. The U.S. should engage Tinubu early and often on the question of what more Nigeria can do to pressure its West African neighbors to end their experiments in military rule — as bad as Nigeria’s security situation is, it could always get worse, especially if Malian and Burkinabe instability contributes to a coup or to further insecurity in Niger, Nigeria’s neighbor to the north. Predictions that all of West Africa will soon fall to jihadists are overblown, but Washington can and should stress to Nigeria that the Sahel region’s problems are already at Nigeria’s doorstep.

The election’s outcome — not necessarily Tinubu’s victory, but the way it unfolded — is a profound disappointment for Nigeria and indeed for all of Nigeria’s partners, including the United States. If there is a silver lining, it is that Tinubu is a talented politician; his rise to the presidency has been more than 30 years in the making. If his health holds (there were rumors of ill health during the campaign), he may prove to be a far more active and engaged manager than Buhari was. (Buhari faced recurring criticisms for slow decision-making and aloofness.) Reform is unlikely, but perhaps a president with greater bandwidth than Buhari can contribute something to the challenging picture in West Africa as a whole.