For the U.S. and Europe, opposing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been a moral crusade. However, to the shock of Western leaders, the Global South — bigger in population and growing in economic strength — has rejected the West’s entreaties to join the battle.

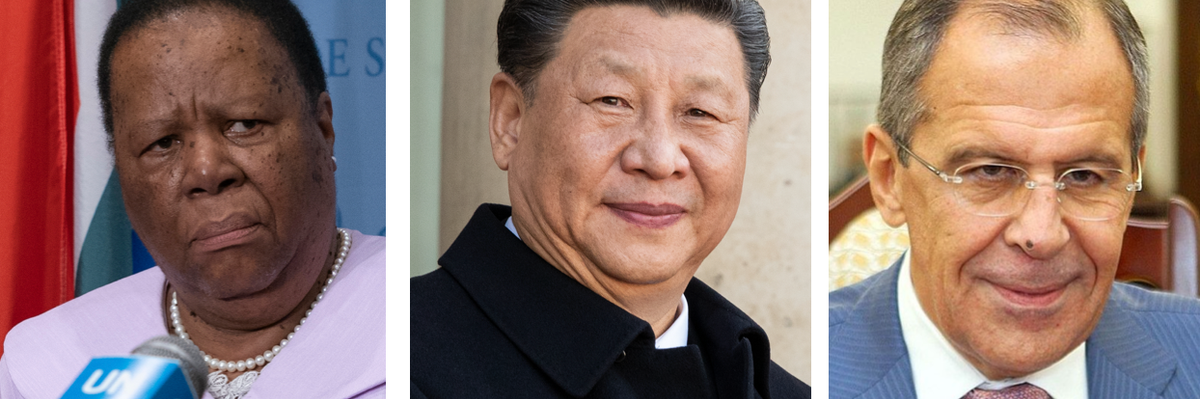

The allies’ sanctimony holds little attraction in capitals bullied by Western governments. South African Foreign Minister Naledi Pandor has claimed that planned military exercises with both Russia and China from Feb 17-24 off the coast of her country were the “natural course of relations” with “friends,” in obvious contrast to joining Washington and Brussels against Moscow militarily.

South African officials now say they want to be neutral on Ukraine, and have even talked about serving as a mediator between Moscow and Kyiv.

Indeed, Pandor indicated that Pretoria no longer urges a unilateral Russian withdrawal, a position that would be “quite simplistic and infantile, given the massive transfer of arms [to Ukraine] ... and all that has occurred [since].”

Furthermore, according to Reuters, Pandor has “accused the West of condemning Russia while ignoring issues such as Israel's occupation of Palestinian territory.”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was criminal and unjustified but should not have shocked allied capitals across the West. Although Vladimir Putin is responsible for choosing war, the West bears substantial culpability for ignoring manifold warnings regarding its dangerous course from even its own analysts.

Like prior wars, there has been little room for dissent. The conventional wisdom is not reasonable, measured support for Ukraine and sanctions on the Russian government, but increasingly all-in on a proxy war against Moscow, almost irrespective of the risk of escalation and retaliation.

This arrogant certainty and escalating irresponsibility has left unease in America and Europe, but as in the buildup to the Bush administration’s 2003 invasion of Iraq elite certainty has swept aside even hints of skepticism and wisps of opposition. Scarcely an editorial is written, webinar shown, speech given, or interview conducted in the nation’s capital that does not urge, indeed, demand greater support for Kyiv. What was once unthinkable — most recently provision of sophisticated Abrams tanks, for instance — has become inevitable.

Similar is the atmosphere in Europe. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s concerns were automatically, if perhaps understandably, dismissed. Yet economic dislocations and energy shocks also triggered popular protests, such as in Prague last fall. A substantial number of Czechs, 42 percent, recently voted for the Euro-populist candidate for the Czech presidency, Andrej Babis.

Indeed, in Europe, at least, many of those backing Ukraine favor a speedy end to combat, an implicit rebuke to the Western mantra that only Kyiv can decide when negotiations should begin. A survey of 10 countries last year, reported the Guardian, “found that despite strong support across Europe for Ukraine’s bid to join the EU and the West’s policy of severing ties with Moscow, many voters in Europe want the war to end as soon as possible—even if that means Ukraine losing territory.”

Continuing schisms were evident in the browbeating suffered by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz over the transfer of Leopard tanks to Ukraine. It was difficult to find a single voice in Washington or Brussels which did not denounce as penurious and lethargic the German response, despite the radical departure from Berlin’s established policy. European and American analysts were as insistent as Ukrainian government officials on action.

Even more notable, however, outside of the U.S.-European axis, plus as few of America’s Asian allies, is the lack of enthusiasm for the West’s crusade. Indeed, of the world’s ten most populous nations, only one, the U.S., sanctioned Moscow. Few were surprised that China refused to declare economic war on its partner Russia. However, India also availed itself of cheap Russian oil. Indonesia maintains its nonaligned course and invited Moscow to the G-20 meeting. Pakistan, Brazil, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and Mexico also refused to join the allied parade.

Indeed, the latter’s president declared that “We do not consider that [this conflict] concerns us.” Also close to home, Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia refused to transfer to the U.S. weapons previously acquired from Russia in exchange for American arms.

Of course, none of these countries formally support Moscow’s war. Some criticized Russian aggression and nuclear fearmongering. But providing an alternative market for banned goods, most importantly oil and natural gas, has kept the Russian treasury flush with cash. Turkey, which is currently blocking the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO, has allowed Russian air service with American-made planes and facilitated Russian acquisition of fuel and spare parts for them. The United Arab Emirates is another aerial windpipe for Russians, especially the privileged and wealthy. Saudi Arabia, too, has tightened relations with Moscow. Such newfound commercial partnerships also likely provide opportunities for sanctions evasion.

Far from joining the general Western diplomatic and economic offensive against Moscow, members of the Global South reached back to their roots in the Non-Aligned Movement during the Cold War. Ewa Dabrowska observed: “As the war against Ukraine has revitalized both the psychology and the geopolitics of the Cold War and the conflict between Russia/the Soviet Union and NATO, India and South Africa have also invoked narratives from that period.”

However, more than simple neutrality is at issue. Alvin Botes, a deputy minister in South Africa, sees creation of a countervailing bloc: “For as long as you have a constellation of interests that is driven from the big powers — sometimes being completely oblivious to the interests of the underdeveloped South — there is a need for the nonaligned movement.”

Western pressure is only likely to strengthen resistance from the Global South. The latter’s current position, according to the Quincy Institute’s Sarang Shidore: is “much less institutionalized, less ideological, and based more on national interests. This makes it more durable and harder to counter through tools that the United States has traditionally employed.” After all, in recent years the West has lost its reputation for both principle and competence.

Developing states see the world as multipolar rather than bipolar, emphasize economic development, have few serious disputes with Moscow (and China), and do not want to choose between Russia and America. Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi explained simply: “we refuse to be a pawn in a new cold war.” Critics of the West can be forgiven for believing that the oft-cited rules-based liberal international order is neither liberal nor rules-based, with its strictures broken whenever Washington chooses.

The Ukraine war has had many lessons, including that Western predominance continues to fade.

South Africa's willingness to conduct military exercises with Russia and China, along with Global South’s resistance to the allies’ proxy war against Russia, suggests that the 21st century might be neither the American nor the Chinese century, but something much more complex.