Recent Ukrainian victories made the Russian government’s declaration of partial mobilization a military necessity from Russia’s point of view. Without this, Russia could not sustain the war in the long term.

The fact that Putin hesitated for so long before doing this — and that the mobilization is still only partial — is a sign of how much he fears the public reaction in Russia. Wednesday’s mass protests against conscription and the huge increase in people trying to leave Russia indicate that he was right to fear this.

It also suggests that the Russian government recognizes the extent of its strategic failure. This, and the fact that in his speech Putin made a positive reference to the peace proposals issued by the Ukrainian government last March, suggest that Russia may now be ready for negotiations, as long as they achieve at least some of the Kremlin's initial goals. But how long will this moment be in our grasp?

The mobilization, of course, is a significant act of escalation in itself (though also a predictable response to recent Ukrainian battlefield successes). What makes it truly dangerous, however, is that this was announced in tandem with Putin’s endorsement of planned votes in Donbas and other Russian-occupied areas in Ukraine over whether those regions will join the Russian federation.

If these areas are annexed by Russia, this will make any peace settlement in Ukraine much more difficult for a long time to come.

The very best that we could then hope for would be a situation like that of Kashmir over the past 75 years: unstable ceasefires punctuated by armed clashes, terrorist attacks, and occasional full-scale war. Along with all the other dangers and suffering caused by such a long-term semi-frozen conflict, it would make it nearly impossible for Ukraine to achieve the sort of progress necessary to join the European Union.

If on the other hand Ukraine looked as if it was going to reconquer these territories, then nuclear war would become a real possibility. In recent months, former Russian officials have told me that the only circumstances in which they can imagine Russia using nuclear weapons (as hinted in Putin’s speech) would be if Ukraine seemed on the point of capturing Crimea — “because Crimea is Russian land, and in the last resort our nuclear deterrent exists to protect Russian land.” If Kherson and the Donbas also become “Russian land,” then presumably the same applies to them.

The window of opportunity for a peaceful settlement in Ukraine is therefore narrowing fast. It does however still exist. This is because Putin has not yet declared that Russia will officially recognize the “results” of the referenda and annex these areas to Russia. It should be recalled that the Donbas separatist republics declared their independence from Ukraine in 2014. However, while Russia supported them militarily, it did not recognize their independence until eight years later, on the eve of the Russian invasion of the rest of Ukraine in February.

This Russian delay was because, in the interim, Russia was engaged in a negotiating process with the West and supported the idea of these areas returning to Ukraine in return for a guarantee of full autonomy. This plan was incorporated in the Minsk II agreement of 2015, which was brokered by France and Germany and accepted by the United States and United Nations. Russia’s progressive loss of faith over the years that Ukraine would ever in fact grant autonomy, or that the West would make them do so, was one key element in Putin’s eventual decision to go to war.

In other words, the possibility still exists that Russia will pocket the “results” of the referendums as bargaining chips for negotiation but will not move to immediate annexation. This will therefore still leave open the possibility of peace talks. We do not know how long this possibility will exist, but given that time may be extremely short, Washington would be wise to urgently explore it. Western governments need to recognize that “deterring” Russia is no longer enough: Ukrainian courage and Western weapons have already defeated Russian plans to subjugate the whole of Ukraine. Instead, we are now in an escalatory spiral with appalling potential dangers for all sides, which it is urgently necessary to break.

Any peace initiative will have to come from the United States. France and Germany are too weak to act independently from Washington. The Ukrainian government’s ability to negotiate is crippled by (understandable) fury at the Russian invasion and Russian atrocities; by pressure from Ukrainian hardliners, especially in the military; and, increasingly, by the government’s own rhetoric, which is committing Ukraine to goals (like the recovery of Crimea) that could only be achieved by total military victory over Russia.

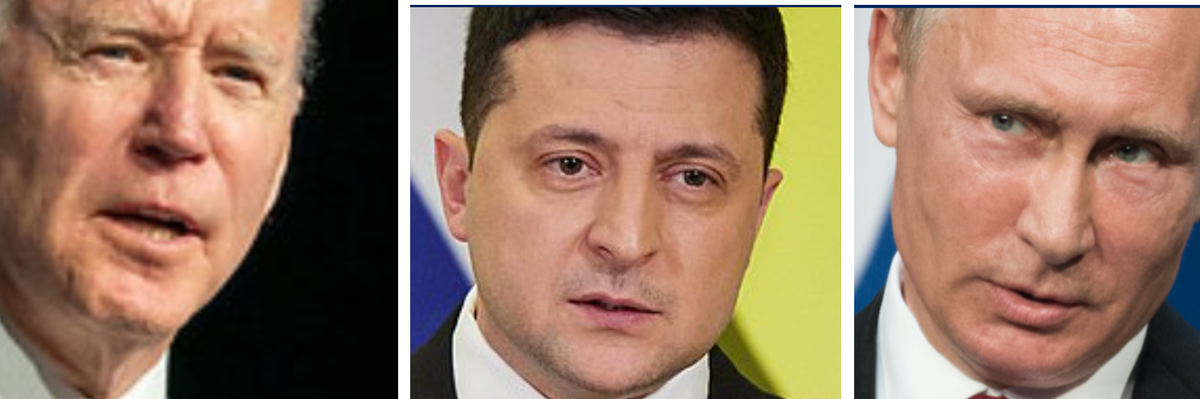

To date, the Biden administration’s position has been that peace negotiations are purely a matter for Ukraine. Together with Russian actions, this stance contributes to making a peace process virtually impossible. It is also both politically and morally wrong. The United States has given military assistance (including intelligence assistance in the killing of Russian commanders) that have made America very nearly a co-belligerent in this war.

This and U.S.-led sanctions against Russia have caused Americans serious economic loss and involved the United States and its citizens in grave risks. The impact on Washington’s allies in Europe and on the world economy has been even worse, threatening key Western partners with food shortages and internal revolt. In the very worst case, America could face the possibility of annihilation in nuclear war.

In these circumstances, to say that the United States has no right to engage in negotiations and put forward its own proposals for peace is an abdication of the Biden administration’s moral and constitutional responsibility to the American people. Moreover, the involvement of third parties in brokering peace settlements and proposing their terms is entirely legitimate in terms of international tradition and America’s own past policies elsewhere.

A peace process cannot be initiated unless both sides abandon preconditions for talks that are completely unacceptable to the other side. A good starting point for talks could be the proposals made by the Ukrainian government itself back in March, which met Russian demands on certain key issues including neutrality. The fact that Putin explicitly and favorably cited Ukraine’s peace proposal in his speech announcing Russia’s partial mobilization may offer a glimmer of hope for diplomacy.

If the Biden administration does not explore this potential chance of peace, the consequences of a continued escalatory spiral could be disastrous for all concerned. Russia has shown that it retains considerable potential for escalation, both in terms of mobilization and the massive targeting of Ukrainian infrastructure and the Ukrainian government — something that is also very likely to lead to casualties among U.S. advisers in Ukraine.

China too has the capacity to greatly strengthen the Russian war effort. So far, China has been extremely cautious and has given signs of unhappiness with the war. At the same time, China has been alarmed and infuriated by U.S. statements (like the latest from President Biden) changing Washington’s position on Taiwan.

For Russia to be gravely weakened by outright defeat in Ukraine would be a severe blow to China’s geopolitical interests, which it is logical to assume that Beijing will try very hard to prevent. American officials should ask themselves whether Putin would have taken these latest steps without at least some agreement from Xi Jinping at the summit in Samarkand last week and what this says about the likely future balance of forces in Ukraine.

War is a highly unpredictable business, and the course of the Ukraine war has defied the expectations of most analysts, myself included. So far, it has done so to the advantage of the Ukrainians. That will not necessarily always be the case. To seek peace and break the present escalatory spiral is in the interests of Ukraine itself, as well as those of America and the world.