“The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia pledged $500 million towards the humanitarian relief effort in Yemen,” proclaimed a June 5, 2020 letter sent to staff of the powerful House and Senate Armed Services Committees by Ari Zimmerman, a lobbyist working for Saudi Arabia. This will help “alleviate the suffering of the Yemeni people,” according to Zimmerman and adds to the more than $16 billion the Kingdom has given to Yemen, making it “the single-largest donor to the country.”

Unmentioned in the letter is that the $500 million donation was the exact same amount Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman spent on his personal yacht, or any reference to Saudi Arabia’s abhorrent track record in the Yemen war. As UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres once put it, “this country is giving money to repair what it is destroying.”

Zimmerman also didn’t mention that he knew many of the letter’s recipients personally, as they were his former colleagues. Before becoming a Saudi lobbyist, Zimmerman was a professional staff member for the House Armed Services Committee. In fact, not even three weeks passed between the time Zimmerman left the Hill — where, according to his official profile at the lobbying firm Brownstein, Hyatt, Farber, Schreck (Brownstein), he was “part of a small group of senior staff” tasked with carrying out the Committee Chair’s agenda — and when he registered as a foreign agent for Saudi Arabia.

While it might be shocking that a congressional staffer who helped shape our national security policy so quickly began working on behalf of an authoritarian regime after leaving Congress, stories like this are not at all uncommon. This so-called revolving door, where former congressional staffers and other government officials transform into lobbyists, is rotating at top speed.

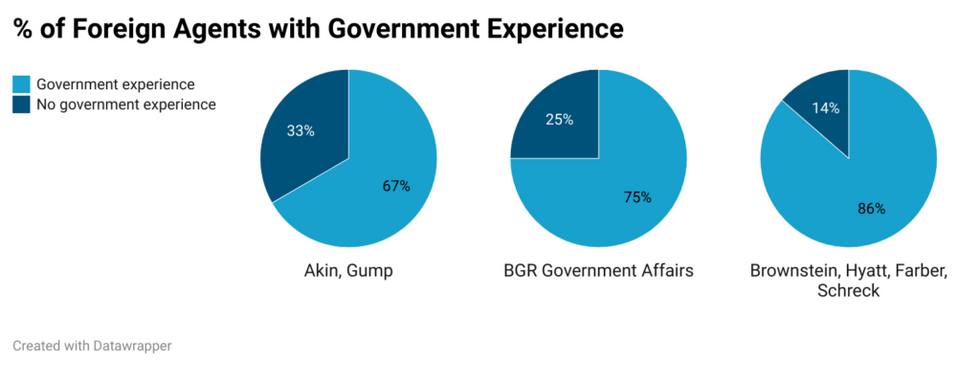

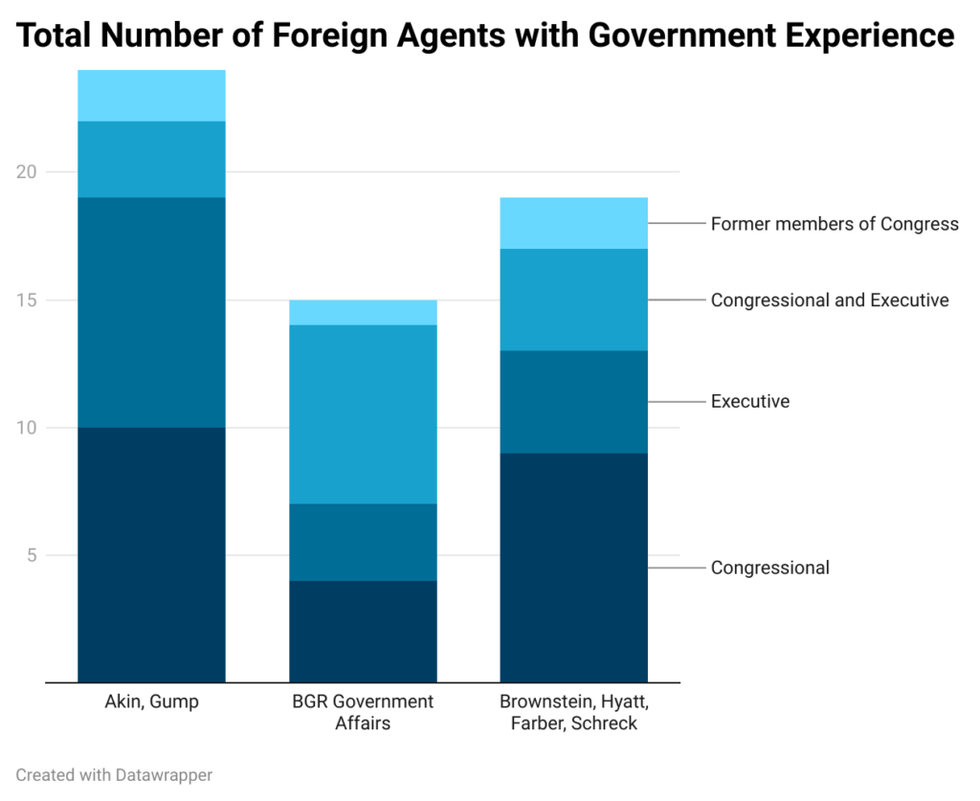

New Quincy Institute research reveals how pervasive this phenomenon is. We analyzed Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) filings of the three highest-earning lobbying firms from 2021 — Brownstein, Akin Gump, and BGR Group — and found that the vast majority of their current registered foreign agents have experience in the executive branch and Congress or, in some cases, were members of Congress themselves.

These government officials-turned-lobbyists come from a range of executive branch departments and agencies, and have often worked in more than one throughout their careers, including the White House. It puts them in a most auspicious position from which to advocate on behalf of a foreign government. For example, State Department veteran Samantha Carl-Yoder, now at Brownstein, contacted her former employer an astounding 56 times in a six-month period in 2021 as a representative of the government of Egypt, either via emails, phone calls or meetings with senior officials. Carl-Yoder inquired multiple times about the status of an attack helicopter sale to Egypt, and even facilitated an in-person meeting in Cairo between herself, former lawmakers-turned-lobbyists Rep. Ed Royce (R-Calif.) and Senator Mark Begich (D-Alaska), and embassy staff.

Many of these government officials-turned-lobbyists also served as staffers for high-ranking members of Congress and on key congressional committees. Far from being shunned by their former colleagues, they’re often welcomed back as lobbyists. As Jeff Hauser, director of the Revolving Door Project, told Politico, they’re “hardly social pariahs to their former colleagues when they leave the Hill for lobbying gigs.”

Between them, approximately half of the foreign agents of Brownstein, Akin, and BGR have experience in the legislative branch, including top staffers for Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.),and Bob Menendez (D-N.J.). Perhaps most notably, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s former chief of staff, Nadeam Elshami, now works at Brownstein where he lobbies the United States on behalf of the government of Egypt, which has arrested tens of thousands of government critics and dissidents, including several American citizens. A former Democratic House aide told the Hill in 2019 that “Pelosi staff who go downtown (to lobby) are hired because they are super smart and know how things work, not because they have special access to her.” Yet, at Brownstein, Nadeam has lobbied Pelosi on numerous occasions, while also making several political contributions to his former boss.

And, it’s not just congressional staff who are churning through the revolving door, members of Congress themselves are cashing in on lucrative work for foreign powers. As we previously wrote for Responsible Statecraft, at least 90 members of Congress have lobbied on behalf of foreign governments between 2000 and today And, all three of the firms analyzed here count former members of Congress among their stable of foreign lobbyists. Brownstein and Akin Gump even boast two former chairs of the House Foreign Affairs Committee in Royce and Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-Fla.), who went on to represent Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, respectively.

In one FARA filing, Ros-Lehtinen even admitted that when she entered Congress she was an outspoken “skeptic” of the UAE, explaining her about-face by declaring that she eventually "fully appreciated the importance of the UAE to U.S. interests in the region.”

As Royce and Ros-Lehtinen’s work would indicate, many of these government officials-turned- foreign-lobbyists are working for authoritarian regimes, and the firms they work for are being paid handsomely by these autocrats. In fact, according to OpenSecrets, the most lucrative FARA client for each of the three firms in 2021 was a Middle Eastern autocracy. Specifically, BGR earned over $1 million representing Bahrain, Brownstein took in $1.35 million to represent Saudi Arabia, and Akin Gump was paid a whopping $4.5 million to represent the UAE.

The experience, knowledge, and connections that these former government officials amassed were not hidden from their clients — they were the main selling points. These and other lobbying firms are all too eager to boast of their lobbyists' government connections to attract clients.

For example, when Brownstein hired Timothy Keating in December 2021, they touted his “over three decades of high-level legislative and political experience,” including in Congress, the White House, and as a lobbyist for Honeywell. Three months after joining Brownstein, he was lobbying on behalf of the Pakistan Embassy.

While it is perfectly legal for countries to dish out millions to firms with well-connected former officials to represent them before the U.S. government, it is worth asking if this undermines democratic debate. After all, these former officials are often lobbying their former colleagues, giving them an instant advantage in influencing policy favorable to the country they are representing.

This incentive structure may also work to encourage them to audition for their future foreign clients while serving the American people, as it’s not uncommon for lobbyist recruiters to headhunt current members and staff while they’re still working in Congress.

In addition, there are national security concerns at play, as many of these former government employees-turned-lobbyists previously had access to top secret information.

“We are allowing members of our government who are privy to sensitive and classified information with political knowhow on how our government works to then use that as guns-for-hire for foreign governments,” Raed Jarrar, the Advocacy Director at Democracy for the Arab World Now, or DAWN, the think tank co-founded by Jamal Khashoggi, told Responsible Statecraft.

Fortunately, some in Congress are well aware of the dangers posed by the revolving door and have taken measures to stop it. Recent bipartisan legislation introduced by Reps. Golden (D-Maine), Porter (D-Calif), and Gosar (R-Ariz.), for example, aims to barsome former government officials from lobbying on behalf of foreign governments. The Fighting Foreign Influence Act would “impose a lifetime ban on former senior U.S. military officers, presidents, vice presidents, other senior executive branch officials, and members of Congress” from lobbying for foreign interests.

While the Fighting Foreign Influence Act is not a broad ban on government officials writ-large — congressional staffers, for instance, are absent from the legislation — it is a vitally important step in the right direction.

“Asking government officials to deny themselves the opportunity to earn millions of dollars lobbying for foreign governments is almost like Mission Impossible,” said Jarrar. “But a lifelong ban on at least some of them is extremely important to protect the principle of democratic governance in our country.”