On Monday, President Biden expressed a willingness to militarily intervene in a potential Chinese invasion of Taiwan — something he has done a few times over the past several months — putting into question the U.S.’s long-held so-called “strategic ambiguity” policy. A recent war game rightfully acknowledged how costly and devastating a major power war over Taiwan can be and that avoiding a conflict altogether would be in all parties’ best interests. However, the war game’s solutions on how to handle the Taiwan issue would likely encourage, rather than deter, a conflict.

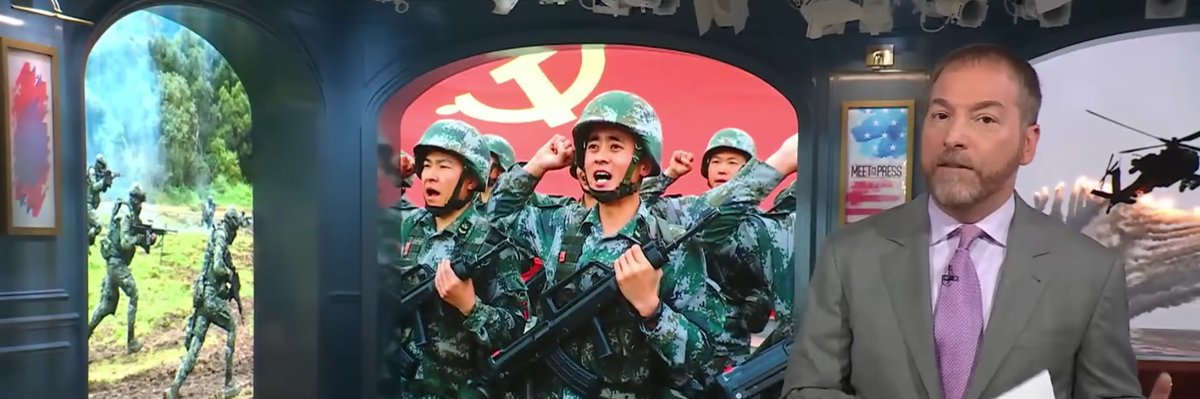

In partnership with the Center for a New American Security, MSNBC aired the war game which was conducted by experts from CNAS and other think tanks, U.S. lawmakers, and former Pentagon officials. It simulated an armed conflict between the United States and China over Taiwan that escalated into a broad, drawn-out regional war involving a nuclear response by Beijing.

But instead of conjuring ways to deescalate, the CNAS/MSNBC war game explored ways of pouring more military capabilities into Asia and getting the support of Asian allies and partners to contain China. Policy ideas exchanged among participants included ending strategic ambiguity and formalizing the U.S. defense commitment to Taiwan, expanding basing in the Western Pacific to redouble the U.S. military presence proximate to Taiwan, and building a NATO-like regional military alliance to enable an extensive deployment of U.S. strategic assets across the Asia-Pacific.

To be sure, the militaristic mindset reflected in the war game is understandable. The main objective of wargaming is to identify preconditions for success in an armed conflict. It is essential for defense analysts to plan for the worst-case scenario rather than simply avoid it. And in many cases, wargaming tends to focus on the conflict itself and pay less attention to all the conditions or actions that produce the conflict. As a result, conclusions drawn from the outcomes of a war game can tend to focus on assessing purely military wartime vulnerabilities and offering a solution for winning the hypothetical conflict rather than addressing the overall policy problem.

Thus, the CNAS/MSNBC war game appeared to largely focus on exploring any means necessary for the United States to maximize its extended deterrence capabilities in East Asia to win a possible war with China over Taiwan, instead of preventing it. The war game’s breathtaking emphasis on militarizing East Asia overlooked how such a radical departure from the status quo can backfire and increase the likelihood of an armed conflict with China over Taiwan.

For example, Washington’s abandonment of its strategic ambiguity vis-à-vis Taiwan can exacerbate Beijing’s historical fear of external interferences and pressures at times of domestic instability and heighten the need to employ force against Taiwan. Chinese elites almost unanimously believe that reunification with Taiwan is a non-negotiable historic mission, and many Chinese citizens are educated to believe the same. China believes it has larger interests at stake than the United States over Taiwan and a stronger political will to engage in an armed conflict. And even if strategic ambiguity endures in rhetoric, an assertive U.S. forward deployment of military bases and assets in the Western Pacific will almost certainly be seen by China as an attempt to keep Taiwan separated from the mainland and trigger highly aggressive behaviors.

Under current conditions of a deepening dependence on deterrence over reassurance, further U.S. militarization in East Asia will be met with corresponding Chinese military balancing efforts. Beijing is unlikely to abandon its longstanding goal of building a military to “defeat anyone attempting to separate Taiwan from China and safeguard national unity at all costs.” As long as China continues to develop and modernize its military and Taiwan remains 100 miles away from the Chinese shore, it will be difficult if not impossible for the United States to gain sufficient military capabilities to coerce China into giving up on seeking reunification with Taiwan by force. And within such a tense and hostile landscape featuring extreme polarization and an intense arms race, the likelihood of a conflict can escalate.

The CNAS/MSNBC war game served the typical role of wargaming, exploring what military conditions might be needed for the United States to counter an attack on Taiwan. But such a militarist solution can be a recipe for turning a hypothetical conflict into a real one, destabilizing the longstanding cross-strait status quo, which, despite a growing sense of competition, remains in peacetime circumstances with no imminent signs of an armed conflict.

The overriding priority for the United States regarding Taiwan should remain on managing tensions and stabilizing the status quo that has kept the Taiwan Strait in peace for decades. A certain level of deterrence is necessary for stability, but just as important is trust-building through diplomatic engagement and credible political reassurances. For now, the Taiwan issue remains primarily a political problem in which political actions that blur or reinforce the original Sino-U.S. mutual understandings to peacefully resolve the issue could increase or decrease the sense of threat involved and the likelihood of using force. China’s possible motivations for aggression and reasoning about the acceptability of options for that aggression can be heavily influenced by political miscalculations.

Avoiding costly political miscalculations will require experts and policymakers to put as much thought into thinking through a simulation of diplomatic scenarios as they do war scenarios. Cross-strait war games are seen more frequently within the U.S. foreign policy community as of late, but peace game exercises to explore ways to normalize the ongoing dangerous erosion of political trust among Washington, Beijing, and Taipei seem to be largely missing.