Foreign policy hardliners have always been threatened by the wisdom of the earliest generations of American leaders, because the warnings of Washington, Jefferson, and John Quincy Adams against foreign entanglements and involvement in distant conflicts are an indictment of the globetrotting militarism that hardliners have championed for decades.

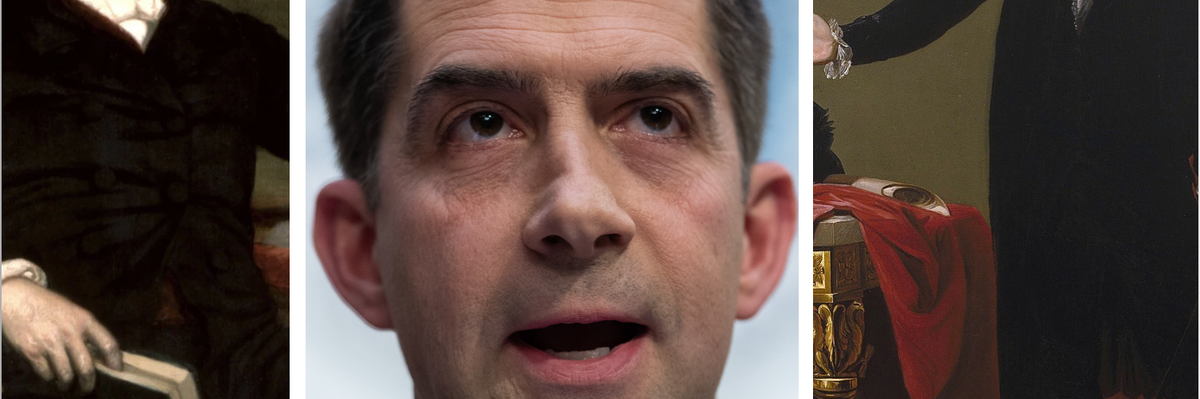

When confronted with the foreign policy vision of the early presidents, Republican hardliners in particular try to deny the substance of what these presidents said and did and hope to co-opt them for their own cause. Sen. Tom Cotton is one of the foremost hardliners in Congress, and he has made a point of trying to claim several early presidents for a foreign policy faction with which those leaders have little or nothing in common.

Whether he chooses to distort the meaning of prudence or ride under the banner of “Jacksonianism,” Cotton wants to dress up his unreconstructed hawkish interventionism as a continuation of radically different foreign policy traditions.

Cotton’s most recent attempt came at a National Review Institute conference earlier this month, where he tried to shoehorn Washington, John Quincy Adams, and Reagan into the same foreign policy approach. The senator justified this odd revisionism by arguing that all three shared the same goals, and it was only the circumstances that had changed. But if they were defined broadly enough, it would be possible to argue that every American president pursues the same ultimate goals, but that definition would be so broad as to be meaningless.

We can and must distinguish between the specific policies and strategies that presidents of different eras have pursued in order to understand and identify them correctly.

Once we move past superficial similarities, it becomes clear just how profound the differences are between the first century of non-interventionist presidents and their post-1898 counterparts. This is hardly news, but many modern Republicans are embarrassed by the first 120 years of U.S. foreign policy because it does not conform to their view of what the U.S. role in the world should be. In order to paper over that contradiction, Cotton tries to pretend that early American statesmen really wanted the same things that he does. He does this to root his own hardline views in the earliest period of U.S. history, but he also wants to deny that non-interventionism and restraint have a long and honorable past in this country.

While he doesn’t refer to any contemporaries by name, there is no question that his misrepresentation of John Quincy Adams was intended as a veiled attack on modern restrainers and other admirers of Adams’ foreign policy of non-intervention and noninterference. Cotton derides modern Americans that look to Adams as an “patron saint” of restraint, feigns “surprise” that anyone might view him this way, and then he asserts that Adams ran an “activist” foreign policy rather than a “restrained and passive” one during his tenure in government.

If this means that Adams could and did sometimes take diplomatic action, it’s true and not very interesting, but if it is meant to imply that he would agree with the sort of activist foreign policy that our government has conducted for the last eighty or one hundred years it is nonsense.

Cotton’s abuse of Adams extends to an anachronistic misreading of the Monroe Doctrine, which he believes is still applicable when it comes to “China’s meddling in Latin America.” Of course, the Monroe Doctrine was never intended as a blanket justification for U.S. interference in the affairs of our neighbors, nor was it a catch-all excuse to oppose the growth of commercial and diplomatic ties between our neighbors and other nations.

Just as the American imperialists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries turned the Monroe Doctrine on its head to pursue their aggressive designs in this hemisphere, Cotton would like to do the same today in the name of opposing China. This is how Cotton picks and chooses what he can twist to advance hawkish goals. While Adams warned that America “goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy,” Cotton can quickly dismiss that as a product of its time with no importance for today, but when Cotton reinterprets the Monroe Doctrine as a justification for anti-Chinese hawkishness he finds it to be “highly relevant.”

It is all very slippery and cynical. We cannot summon Adams’ ghost to ask him what he thinks of these dishonest distortions of his ideas, but it is reasonable to assume that he would not be on the side of the distorters.

George Washington receives similar treatment, as Cotton tells us that the Farewell Address should still “guide us today, though not in any kind of automatic or reflexive way.” One looks in vain for evidence that Cotton is guided by Washington’s words in any way. When Washington enjoins his fellow Americans to “observe good faith and justice towards all nations,” one might think that this advice is timeless, but it is advice that we know Cotton rejects. He has not only been one of the leading opponents of the nuclear deal with Iran, but he encouraged Trump to renege on the agreement and break all the commitments that the U.S. made.

He has likewise been a vehement opponent of all arms control treaties, and he successfully urged Trump to pull out of both the INF and Open Skies Treaties. Washington urged Americans to “cultivate peace and harmony with all,” but Cotton is eager to stoke existing conflicts and start others. Among other things, he has been one of the loudest advocates in Congress for attacking Iran. Washington had his own reasons for warning against “permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular nations,” but his advice has never been more relevant when we see what unchecked anti-Iranian hostility has done to our policies in the Middle East.

Cotton insists that “circumstances matter a lot,” but he and his fellow hardliners have proven to be oblivious to changing circumstances in the world in recent decades. He would have the U.S. continue pursuing the same strategy of global “leadership” and dominance as if nothing had changed since 1991 or 2008 or any other point. If circumstances matter so greatly, the U.S. ought to alter its strategy to fit the world as it is today, but Cotton has no interest in any of that.

Given his druthers, Cotton would have the U.S. double down on every commitment and entanglement and add to them in virtually every part of the world. In an earlier speech at the Reagan Library, Cotton said, “Our citizens deserve a foreign policy that puts their interests over ideology. That does not seek war, but will not tolerate defeat.” Americans do indeed deserve a foreign policy that privileges their interests and doesn’t seek war, but if Tom Cotton has his way with his revisionism and hardline policies we can be certain that they will get none of that.