As the United States closes the door on its two-decade war in Afghanistan, the last person the American people need to hear from is the man who not only contributed to the war being prolonged a decade, but who wants it to continue for another (or more).

And yet here is “King David” Petraeus, former commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, riffing in a casual interview with The New Yorker about how his counterinsurgency ideas were never given a large enough time frame to succeed, and hocking the same “lessons” he’s been repeating for years.

Should the man who lengthened and exacerbated the United States’ defeat really be the one being consulted and treated to front-page retrospectives?

He has company, unfortunately. Author and Washington Post contributor Max Boot wrote in a 2019 column that our conception of military deployments must be in generational, or even centurial, terms:

“These kinds of deployments are invariably lengthy and frustrating. Think of our Indian Wars, which lasted roughly 300 years (circa 1600-1890)...U.S. troops are not undertaking a conventional combat assignment. They are policing the frontiers of the Pax Americana.”

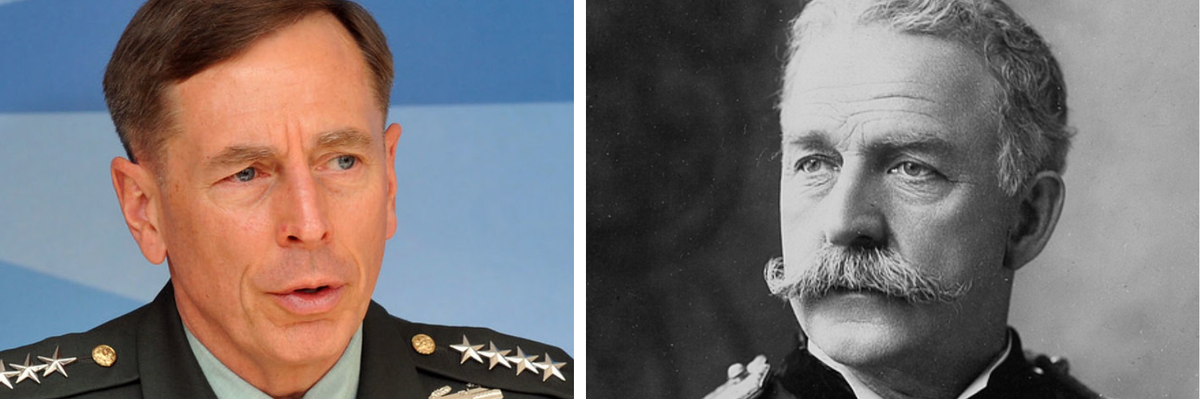

Boot conjures an arresting mental image: David Petraeus in dress blues and sabre attempting to pacify the Dakotas as poorly as he did the Hindu Kush. But perhaps the 4-star fits better into the scenario than he may like to admit. Not as Philip Sheridan or George Armstrong Custer, but as a soldier whose persona, ambitions, and techniques mirror Petreaeus with startling similarity: Nelson A. Miles.

Let Boot’s chosen analogy be a launch point for a 19th and 21st century juxtaposition. By comparing and contrasting David Petraeus with his closest historical model, we can carve out the traits that make the man — and demonstrate why he should keep his advice to himself.

Nelson Appleton Miles was born on his family’s Massachusetts farm in 1839. He joined the Union Army in 1861 as a volunteer and served with distinction, being wounded four times and receiving the Medal of Honor for his service at the Battle of Chancellorsville.

Both Miles and Petraeus chose careers as soldiers, and both proved to be lucky in love, marrying the daughters of prominent families. Following the Civil War, when he was at the rank of colonel, Nelson Miles married Mary Hoyt Sherman, niece to both Senator John Sherman of Ohio and General William Tecumseh Sherman. Likewise, when Petraeus was studying at West Point in the early 1970s, he began dating and eventually married the daughter of the superintendent, General William Knowlton.

Miles spent the next two decades on the western plains fighting American Indians before becoming Commanding General of the U.S. Army. He never lost a battle — accepting the surrender of Chief Joseph, Geronimo, and Sitting Bull — but irritated his fellow officers with his insatiable ambition and desire for public recognition.

The press back East obliged. According to historian Louise Carroll Wade, newspapers “praised his bravery, dedication to his soldiers, regal bearing, and eagerness to star in civic parades, ceremonies, and banquets.” Broadfaced and handsome, he drew the attention of New York and Washington high society whenever he visited. Daniel S. Lamont, Secretary of War under President Grover Cleveland, referred to Miles as “a newspaper soldier.”

More than a century later, David Petraeus received the same media treatment. From the moment he graced the cover of Newsweek in 2004 as “Iraq’s Repairman,” he became the fixation of journalists eager to sire the image of a George Patton for the Global War on Terror. In 2007 the neoconservative Weekly Standard crowned him “Man of the Year.” CNN’s Peter Bergen, a continuous Petraeus hype man going back over a decade, labeled him “the most effective American military commander since Eisenhower.” Bing West at the Wall Street Journal compared him to Marcus Aurelius. During the peak of Petraeus’ public acclaim, from around 2007 to 2012, NBC News called his very name “a kind of gold standard of integrity and competence.”

The late Michael Hastings, who was better than anyone at exposing the media’s “superhuman myth” around Petraeus, often quoted the general’s 1987 doctoral dissertation to reveal the general’s true life lesson. “What policymakers believe to have taken place in any particular case is what matters — more than what actually occurred,” Petraeus wrote. “Perception” to the people in power matters more than victories or defeats on the battlefield. And that’s just how David Petraeus fought his wars. As even the New York Times had to concede in 2007, “General Petraeus gives the disturbing impression that he, too, is more focused on the political game in Washington than the unfolding disaster in Iraq.”

Nelson Miles’ attempt to utilize Petraeus’ perception ethos was even more lackluster. During the Spanish-American War, he was placed in command of the invasion of Puerto Rico, the cap on his forty year military career. Landing on the island in “full dress uniform and all his medals,” Miles read proclamations about how the natives were about to be blessed with civilization. Resistance to the Americans was so flaccid however that “some towns surrendered to startled reporters.” And the ten-week war ended before Miles’ army could even capture San Juan. His grand campaign was, in the words of war correspondent Richard Harding Davis, “nipped by peace.”

The embarrassment was thorough. Chicago satirist Peter Dunne joked that Miles’ medal-adorned uniform be seized by Congress to strengthen the gold reserve. The gaudy display led Theodore Roosevelt to dismiss Miles in private as “merely a brave peacock.”

The closest resemblance between David Petraeus and Nelson Miles is, however, their shared resistance to reorganization and dedication to outdated military doctrines.

Military historian Russell Weigley judged Miles to be the weakest Commanding General “since the inception of the post.” With his “haughty and cantankerous” personality, “he quarreled continually with Secretaries Daniel Lamont, Russell Alger, and Elihu Root.” A traditionalist, he believed a soldier should have a stronger voice in military policy than any civilian secretary. And his personal disposition, wrote contemporary historian Henry Adams, was “diseased with vanity and egotism.”

Miles led the opposition to the reorganization of the military into the modern General Staff system, feeling threatened that it would decrease the power of his position. “Though he possessed courage in abundance, he wasn’t particularly endowed with vision or imagination,” assessed historian Robert W. Merry. So “active, alert, energetic, and ingenious in devising methods for… thwarting” the reform bill according to Harper’s Weekly, the General Staff system was not instituted until one week after Miles’ retirement in 1903.

Despite nurturing his own image as a reformer and thoroughly twenty-first century commander, in reality David Petraeus is just as traditionalist and adverse to structural change as Miles was. Petraeus’ baby, Field Manual 3-24 (co-written with General James Mattis in 2006), lays out his conception of counterinsurgency (COIN) through the strategy of clear-hold-build.

This form of nation-building — holding territory for long periods to build local institutions after clearing out the enemy — has little practical difference from the “hearts and minds” campaign of Vietnam. And they have the same failed outcome; occupiers have neither the timetable or the sufficient goodwill of the locals to develop alternative (and usually alien) institutions to compete with the native resistance. Petraeus fails to see either the inadequacy of the tactic or the impossibility of the mission, and instead advocates for a likely endless war in Afghanistan and elsewhere. While other Americans recognize how peripheral and destructive these Middle East interventions are to the U.S. national interest, David Petraeus remains blind to the ineffectiveness of his precious COIN.

A need for self-importance derailed the potential post-retirement public careers of both men. Miles’ false but sensational accusations that Chicago meatpackers supplied the U.S. Army with chemically processed, “embalmed” beef led to a souring in his relationship with the press, and bad blood over the General Staff reform led to his departing the military without the customary honors or ceremonies. Meanwhile “King David” abdicated under the cloud of scandal himself, having divulged national security secrets to his biographer (and lover) to bump up his image, causing his resignation as Director of the CIA.

If Petraeus ever had presidential ambitions (something he always denied), Paula Broadwell buried those odds. Nelson Miles did run for president in 1904, but received only three delegate votes at the Democratic National Convention. When Miles died in 1925, he became one of only two people buried in mausoleums at Arlington National Cemetery.

After Miles’s public image cratered, Henry Adams remarked that during his remaining years Miles was left “quite unconsulted and unconsidered.” If only David Petraeus — who duplicates Miles’ naked ambition, headline chasing, phony perception, and predelication for scandal — would share the same fate and spare the rest of us.