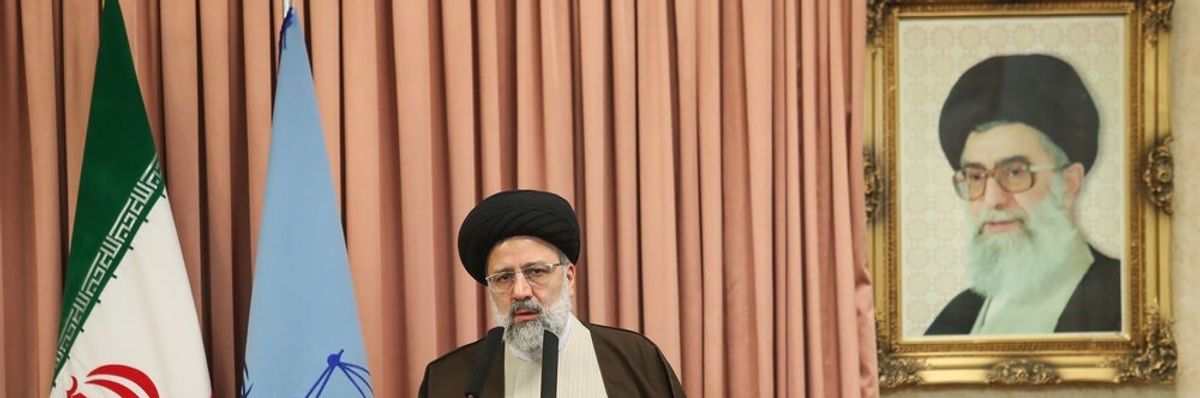

Like the rest of Iran’s neighbors, Armenia and Azerbaijan are trying to make sense of how the country’s newly elected conservative president Ebrahim Raisi may change Tehran’s orientation toward the region.

Seen from an Azerbaijan perspective, continuity with the policies implemented by the outgoing moderate administration of Hassan Rouhani would be the preferred course. In his congratulatory message to Raisi – who won a stage-managed election on June 19 and is slated to take office in August – Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev commended the “strategic cooperation” between the two countries. Significantly, Aliyev emphasized that the full re-establishment of the Iranian-Azerbaijani border as the result of the 2020 war “opens up new opportunities for regional cooperation.”

Some analysts in Baku interpreted this as an invitation to Iran to become a stakeholder in the new post-war order in the South Caucasus. Indeed, despite some specious claims from Azeri ultra-nationalists and American anti-Iran hawks, Tehran has not in any way thwarted Baku’s war effort, and in fact has consistently supported Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity.

Armenia, by contrast, is emerging from an extremely traumatic period – a painful loss in the war against Azerbaijan last year and polarizing national elections in June. It has yet to produce a coherent foreign policy strategy suitable for the new realities. As usual, among foreign powers Russia loomed largest in the elections. Some Armenian analysts, particularly those sympathetic to the opposition, now hope for some sort of Moscow-Yerevan-Tehran realignment to counter the Baku-Ankara alliance. Re-elected prime minister Nikol Pashinyan, with a renewed and strengthened mandate in the parliament, however, seems more likely to seek a peace deal with Azerbaijan than attempt to balance Azerbaijan and Turkey with Russian and Iranian help.

That may be just fine with Tehran. Raisi’s top priority is to address the country’s desperate economic situation. Since his election is widely seen as a steppingstone to succeed Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, he needs stability on the country’s borders to focus on its manifold internal challenges. There is a consensus in the Iranian security establishment that the Middle East and Persian Gulf are arenas of vital national security interest, and that the South Caucasus is not. In addition, Afghanistan, during the rapid withdrawal of American forces, is fast emerging as another source of threats for Iran. These regions remain priorities irrespective of who occupies the Iranian presidency.

Iran’s relatively low-key involvement in the South Caucasus could, however, shift if its threat perception regarding Turkey and Azerbaijan grows more acute. Iran sees Turkey’s alliance with Azerbaijan and growing ambition in Central Asia as directed against its interests. Turkey’s military involvement in the region raises the specter of an expanding NATO presence around Iran’s borders.

It also revives Tehran’s fears of Azerbaijani anti-Iranian irredentism. Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan himself fueled these fears in December by appearing to have designs on Iran’s northern provinces, home to many ethnic Azerbaijanis. While Baku does not officially endorse calls for a secession of “south Azerbaijan,” it does support anti-Iran scholars from hawkish Washington institutions which consistently seek to inflame Azerbaijani separatism in Iran.

Iran is also worried about the implementation of a provision of the Russian-sponsored ceasefire deal that establishes a direct land corridor between Azerbaijan’s mainland, its exclave of Nakhichevan, and Turkey through Armenian territory, bypassing Iran. Fearing the potential loss of its border with Armenia as a result, the chair of the national security committee of the Iranian parliament Mojtaba Zonnour in May expressed Iran’s strong opposition to any change in the internationally recognized borders in the South Caucasus. This elicited a thunderous reaction from a leading pro-regime website in Azerbaijan which accused Iran of a “treacherous stab in the back of Azerbaijan.” Such incidents have brought to light the underlying tensions in relations between Baku and Tehran.

Another major irritant for Tehran would be expanded Western and Israeli intelligence activity on its northern borders. Some ostensibly pro-Azerbaijani analysts in Washington think-tanks have been issuing provocative calls to that end. The veteran conservative scholar Walter Russell Mead openly called in a June Wall Street Journal op-ed to use an entire ethnic group – Iranian Azerbaijanis – as a source of intelligence gathering for Iran’s adversaries.

These trends would prompt any Iranian government, whatever its ideological hue, to build up its deterrence capabilities in the South Caucasus. Raisi’s conservative background and closeness with the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps would ensure a greater harmony between the diplomatic and security fields and a greater overall securitization of ties.

Such a turn would not be something new. During the hardline presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad from 2005 to 2013, relations with Azerbaijan were tense, to the point that Iran’s chief of the general staff, Major General Hassan Firouzabadi, threatened the Aliyev regime with a “people’s awakening.” While Raisi’s presidency may turn out to be very different from Ahmadinejad’s, there remains a potential for increased tensions.

Baku could profit from such tensions. They would boost Azerbaijan’s perceived geopolitical value as an American and Israeli ally against the “Iranian threat.” They would also benefit the regime internally: With a hardline president in Iran, it is always easier to sell internal repression as a necessary measure against “Iran-supported extremists” – a tactic long favored by Baku to stifle dissent. Recently approved legislative changes further limiting the scope for independent religious activity in the country, which many see as targeting Shiite believers, lay the groundwork for more such restrictions in the future.

Incentives for restraint

However, Raisi’s hardline credentials would at the same time also ensure that whatever conflict might arise will not spiral out of control. He supports the Vienna talks to restore the nuclear deal between Iran and the world powers, but also echoes the conservative establishment’s skepticism of deepening ties with the West, particularly the United States. Iran’s perpetually dysfunctional relationship with the West increases its economic reliance on regional players, including Turkey and Azerbaijan.

In case of Turkey, Tehran has additional incentives for restraint: Its relations with Ankara resemble a complex chessboard, where South Caucasus is but one aspect. As political Islam and anti-Western discourse recede in Turkey, and conservative right-wing nationalism rises, Tehran is calculating that any post-Erdogan Turkish leader may be more hostile to Iran.

The coming years in the South Caucasus will see an increased scope for conflict between Turkey and Azerbaijan on the one side, and Iran on the other. That would have been the case under any president in Iran. The election of the conservative Raisi augurs a more hard-nosed, security-driven approach by Tehran toward the region. At the same time, economic interests, particularly if Iran’s relations with the West continue to stagnate, should mitigate the risks of an all-out confrontation.

This article has been republished with permission from Eurasianet.