Is Joe Biden the new LBJ on foreign policy? That was the provocative suggestion Peter Beinart made a couple weeks ago when he was commenting on Biden’s early domestic policy successes and his relative timidity in foreign affairs.

Like Lyndon Johnson, Biden has pursued an ambitious domestic agenda and has had some major legislative successes, including the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act, but so far on foreign policy he has been slow to act and he has been reluctant to challenge hawks in Washington and in his own party.

Moreover, like LBJ, Biden fears being called a weak appeaser, and so he has dragged his feet on rejoining the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and has been trying to placate hawkish senators. For the last 60 years, Democratic presidents have been stuck in what has often been called a “defensive crouch” on foreign policy and national security, and Biden is doing much the same thing. If there is going to be a shift away from our current militarized U.S. foreign policy, Democrats will have to get out of the “defensive crouch” and reject the hawkish assumptions that their party leadership has internalized for more than half a century.

Ever since Cold War hawks blamed President Truman for “losing” China (a ridiculous accusation), Democratic administrations have been terrified of appearing “weak” in the face of foreign threats, and they have embraced destructive “tough” policies to avoid that perception. Most of the time, Democratic presidents have harmed themselves and the country by staying in the “defensive crouch.” They have saddled themselves and the country with dead-end policies that they could dismantle if they were willing to make the effort.

Fear of being accused of “weakness” was an important factor in Johnson’s decision to commit the U.S. to escalate in Vietnam. That same fear has warped the decision-making of Democratic administrations and the foreign policy debate among Democrats ever since. LBJ didn’t want to be accused of “losing” another country to communism, so he waged a ruinous and unjust war that killed millions, including more than 50,000 Americans.

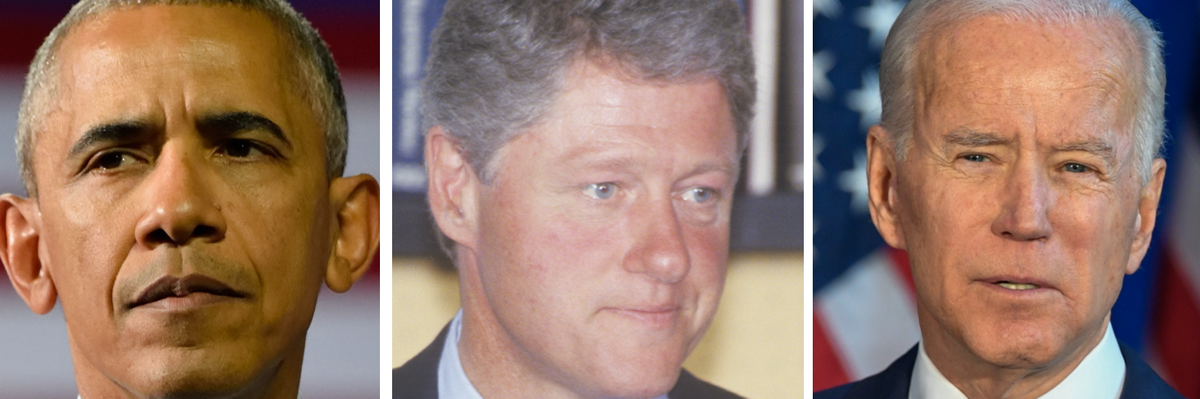

Carter heeded his national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski’s hawkish advice on a number of issues and declared the Carter Doctrine, which laid the groundwork for our deepening entanglement in the Middle East over the last 40 years. Clinton mired the U.S. in the region further with the “dual containment” of Iran and Iraq and normalized frequent uses of force to police distant parts of the world. Obama backed the Saudi coalition attack on Yemen so that he wouldn’t be accused of “abandoning” these clients in the wake of the JCPOA (he was accused of this anyway). Biden’s apparent continuation of Trump’s Iran policy is another example of making poor policy decisions out of fear of hawkish criticism. We are seeing much of the same thing with respect to the “war on terror,” relationships with U.S. clients in the Middle East, the increasingly confrontational approach to China, and our bankrupt policies toward Venezuela and North Korea.

Instead of challenging Republican hawks’ basic assumptions, Democratic presidents and presidential candidates have often echoed their rhetoric and accepted their framing of the issues, and as a result they box themselves in to continuing policies that they have previously declared failures. Democratic presidential candidates have most often run against Republican failures on foreign policy by casting themselves as the better, more competent managers of the same misguided strategy. That was how John Kerry ran against Bush, and it is how Clinton wanted to run in 2008 if she had been nominated. The candidates that mount more direct challenges to the status quo are deemed “unelectable” by the party’s leaders and donors.

The end of the Cold War might have allowed Democrats to come out of this crouch, but instead the party concluded that the only way to win the presidency again was to ape Republican hawkishness in the post-Cold War era as well. The post-9/11 atmosphere was even worse. Democrats were desperate not to appear “weak” on terrorism and the Democratic politicians that aspired to be president didn’t want to be caught on the temporarily unpopular side of opposition to the Iraq war, and that meant that most of the Democratic presidential field in 2004 and 2008 had supported the war and many of them had voted to authorize it.

Biden’s personal “defensive crouch” on foreign policy really began in the aftermath of the Gulf War, which he had initially opposed. From then on, Biden strove to be reliably hawkish on foreign policy on the assumption that this was the politically safe position to take. He supported Clinton’s military interventions in the 1990s, and then voted to authorize the invasion of Iraq under Bush. When he joined the Democratic ticket in 2008, Biden was the conventional hawkish establishment figure included to “balance” Obama’s anti-war rhetoric.

Even Barack Obama, who came closer to getting out of the crouch than any previous Democratic president had, conducted a foreign policy that sought to silence hawkish criticisms by giving the hawks most of what they wanted on many issues. Even when he pursued engagement, he usually did it by piling on sanctions first, and he still felt the need to compensate for engagement with Iran by setting a record in weapons sold to Middle Eastern clients.

Obama made a habit of initially resisting hawkish demands only to give in to them a bit later in slightly watered-down form. He ridiculed the Washington “playbook” for military action, but he involved the U.S. in multiple wars without Congressional authorization after explicitly denying that the president could do that when he was a candidate. Republican hawks rarely credited him for these actions, and they just agitated for ever more aggressive policies while continuing to accuse him of “retreating” from the world.

The Obama administration’s experience may be the best evidence we have that there is no point for Democrats to staying in the “defensive crouch” on foreign policy. Even though Obama ran a mostly conventional center-left foreign policy, he was constantly attacked for “apologizing” for America, rejecting American exceptionalism, and abandoning allies. It didn’t matter that none of these attacks was true. Obama’s frequent uses of force, his explicit affirmation of American exceptionalism, and his disastrous indulgence of U.S. clients in the name of “reassurance” did not protect him or his foreign policy agenda from the hawks’ inevitable bad faith attacks.

That is the basic problem with letting your opponents set the terms and limits of debate. Hawks will repeat the same attacks on Democratic administrations no matter what they do or don’t do, so they may as well follow through on their campaign promises and reject the policies that they know to be failures. Biden ought to rejoin the JCPOA as soon as possible and stop worrying about what hawkish saboteurs will say about it. He should honor his commitment to treat Saudi Arabia like a “pariah” because of the crimes of the crown prince and their government. Instead of continuing failed Trump-era policies, he should be overturning them and building something better in their place. “Diplomacy is back” shouldn’t just be an applause line, but rather a statement of how Biden will govern differently from his predecessor.