The events of the summer of 2020 drove Americans’ sense of national pride to historic lows. For many Americans, footage of federal troops attacking protesters in U.S. cities evokes images that Americans are more accustomed to seeing in authoritarian countries. Although the news cycle has largely moved on, state and local governments continue to violate the rights of Americans protesting police brutality; meanwhile, U.S. condemnation of human rights abuses abroad increasingly rings hollow.

Yet from the perspective of many non-Americans, the United States’ commitment to human rights has long been insincere. The hypocrisy of U.S. support for human rights is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in the Middle East. The American government’s long-standing support for regional dictators, regardless of the crimes they commit against their own citizens, sends the message that the United States will not use its leverage with these governments to protect human rights, a point clearly demonstrated by news this week that the State Department cleared arms sales to these same dictatorial regimes without considering the risk of civilian casualties. This is abundantly clear to local citizens, yet remains difficult for many Americans to comprehend. While Americans are aware that the U.S. does not always live up to its more noble aspirations abroad, many continue to insist that U.S. control in the region represents the least bad option for its inhabitants.

Many Americans tend to assume that U.S. military dominance in the Middle East is preferable because the United States will support a notion of human rights in its own (self) image. By logical extension, control by a non-democracy such as China or Russia would engender authoritarian injustices. Yet asserting that the region’s inhabitants would suffer in the absence of the U.S. military ignores the suffering the region has endured as a result of the U.S. military’s presence. Paying lip service to humanitarian concerns while actively pursuing American military hegemony undermines good faith efforts to protect human rights.

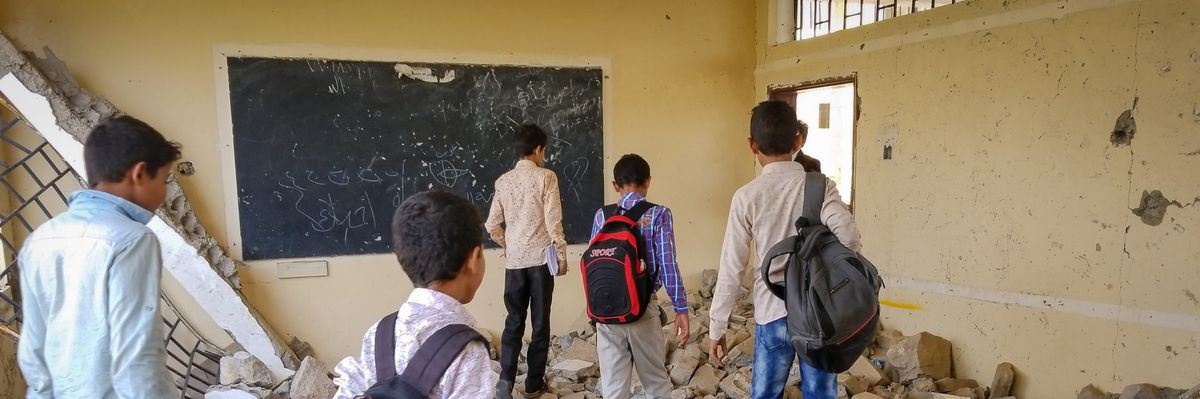

A recent report from the Quincy Institute argues that the U.S. should condition engagement with security partners on addressing human rights concerns. At present, the U.S. makes no such demands. For the population of Yemen, U.S. support for the Saudi-led coalition has, in fact, extended the war. Under both Presidents Obama and Trump, the U.S. government has exhibited little concern for Yemenis’ rights and lives. From Yemen’s perspective, Chinese or Russian control could hardly be worse.

Meanwhile, Saudi dissidents have lost hope that the U.S. might finally use its leverage to rein in government repression that has significantly intensified under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The UAE’s abuse of citizens, inhabitants, and even visitors also tends to go unremarked.

For the population of Egypt, U.S. military aid continues to prop up the regime of President Sisi, empowering him to persecute anyone suspected of disloyalty, including U.S. citizens.

The oldest blemish in the illusion of U.S. support for human rights in the Middle East has been America’s willingness to both tolerate and fund Israel’s disregard for Palestinians’ rights over decades of occupation.

The U.S. continues to maintain relationships with these abusive regimes because doing so serves its goal of military hegemony in the region. Until the U.S. abandons this unnecessary and costly objective, it will continue to fund and arm dictators eager to drag it into additional conflicts.

Despite our dismal record of shoring up authoritarianism, the reason so many Americans persist in the belief that the U.S. is the region’s best hope for human rights is that many of us would like it to be true. Americans continue to believe, or to wish we could believe, in the image of our country as a beacon for democracy.

American hypocrisy in the Middle East did not begin with the Trump administration. For that reason, even if presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden wins the election, he cannot simply revert to a pre-Trump foreign policy. If Biden wishes to contribute to meaningful stability in the region, the U.S. needs to adopt a completely new paradigm in its approach to the Middle East.

The first step actually requires a shift in domestic policy: the United States must address the systemic injustices resulting from white supremacy. Governments around the world are watching to see how the U.S. handles the current crisis of legitimacy, as governing institutions struggle to respond to popular demands to rectify human rights abuses endemic in American law enforcement. Admitting to mistakes and adopting reforms would offer a model for security partners to follow, while disarming rivals who revel in American hypocrisy.

The next step is for the American government to adopt a multilateral approach to human rights. The U.S. and the region would be better served by prioritizing multilateral engagement, where the U.S. acts as one of many interested parties, rather than undertaking the costs and responsibilities that result from the unilateral use of force. By modeling diplomatic involvement in a multilateral process, the U.S. would strengthen international cooperation while earning greater respect, opening the door to more constructive interactions with governments currently seen as adversaries.

But acting multilaterally requires letting go of America’s longstanding pursuit of regional hegemony. Only embracing a new paradigm for U.S. involvement in the region, one premised on cooperation and diplomacy rather than coercion and aggression, will allow the U.S. to act in a manner that aligns with the values that many Americans still believe distinguish this country.

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org