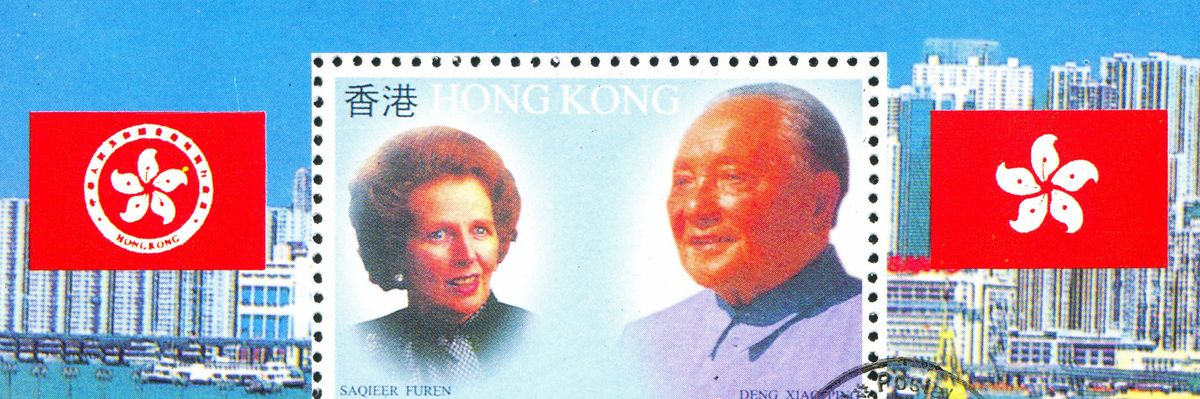

In 1984, a satisfied Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher announced her government’s agreement with Deng Xiaoping’s China over the eventual return of Hong Kong in 1997. A century before, Great Britain had used its military superiority to detach Chinese territory through grant and lease for the colony of Hong Kong. But the lease would soon expire, ending London’s legal claim to the territory.

Of course, the original transaction was both legal in that the document was legally enforceable and illegitimate, in that it was effectively concluded at gunpoint. International norms and geopolitics have since changed, so Thatcher, the famed “Iron Lady” who negotiated with Mikhail Gorbachev and defeated the Argentine junta, reached agreement with China’s reformist “paramount leader” Deng Xiaoping to return Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China.

The deal remained less than satisfying to many who valued human liberty. Two imperious states bartered over the fate of several million people, who were not adequately consulted in the transaction.. Wealthy Hong Kong residents began looking for the exits. Hong Kongers were to be transferred to Beijing only shortly after the death of Mao Zedong, who had presided over mass famine and conflict.

Emily Lau, an influential reporter from the colony, asked Thatcher at the time: “Prime Minister, two days ago you signed an agreement with China promising to deliver over five million people into the hands of a communist dictatorship. Is that morally defensible, or is it really true that in international politics the highest form of morality is one’s own national interest?” Thatcher defended her handiwork, noting that it was widely praised in Hong Kong and expressly protected the territory’s unique liberties.

All true then, nearly four decades ago. Alas, as the Nikkei’s Katsuji Nakazawa noted last week, “Lau’s concerns became a reality.” After Beijing imposed its national security law backed by PRC security personnel on Hong Kong, Thatcher’s safeguards disappeared. The liberty to criticize, debate, and protest will be severely circumscribed. Many people still hope they can self-censor and go on with life. However, the legislation also mandates closer regulation of the media and internet, which likely means expansion of the mainland’s stultifying informational censorship to heretofore free Hong Kong. We likely are witnessing the closing of the free Chinese mind in the territory.

The terms of the turnover were never enforceable. An agreement benefited Beijing, since resort to violence against British rule would have ruined Beijing’s campaign to become like other nations. But the territory’s future depended upon Chinese restraint, which in turn reflected the PRC’s desperate need to enter the world economy and access Western markets. Hong Kong long had facilitated East-West contact and accounted for roughly a fifth of China’s total GDP. That would change over time, however, and the restraints to which the PRC agreed were inevitably temporary. After which Beijing would be free to act as it wished.

An ugly reality, to be sure. Still, that doesn’t mean that Thatcher was wrong. Should she have played a dangerous, and potentially reckless, game of chicken with Hong Kong and its people?

The British government could have looked ahead at the 1997 expiration date and declared that the fate of several million people should not be disposed of by a rarified negotiation over juridical niceties tied to a past world that no longer existed. People should be able to decide on their own futures. Thus, Her Majesty’s Government, represented by Margaret Thatcher, could have declared plans to hold a referendum, allowing Hong Kongers to choose their future: remain a British colony, return to China, or become independent. Assume the first option prevailed — residents had been spectators to years of mainland madness next door and would have been unable to easily sustain an independent existence. What would have happened?

Beijing would have responded angrily but likely avoided war. In 1997, when the lease formally expired, China’s GDP was little more than half of the UK’s and about a tenth of America’s. Beijing had not fared well militarily when seeking to teach Vietnam “a lesson” in 1979. Although the PRC was a nuclear power, so were London and Washington, which would have been on Thatcher’s speed dial to back up the British.

More important, the PRC was only beginning its economic Long March, reforming its economy and entering foreign markets. Conflict would have interrupted that process, with long-term negative impacts. The pragmatic Deng likely would have played the long game, avoiding a direct confrontation until he or his successor was sure of winning.

In the meantime, however, Hong Kong would have become an increasing burden on the United Kingdom, which probably would have been locked out of the newly expanding Chinese market. The right mix of verbal threats and military deployments by Beijing would have forced the UK to maintain a battle-ready garrison with sufficient back-up — perhaps an aircraft carrier permanently berthed in the harbor — just in case. Doing so would be difficult and expensive for London.

Beijing could have isolated the colony and systematically harassed British rule. The result would not just have inconvenienced residents and burdened London. Many foreign companies would have avoided settling in Hong Kong; some established firms would have left for safer and more hospitable havens elsewhere, such as Singapore. How long would UK governments have held firm as other European countries and America raced to fill the growing Chinese market?

Hong Kong illustrates the drama and tragedy of international relations. Surely it was awful to hand the territory back to the PRC. However, London had no obligation to enter into a long-run and likely losing conflict with China over the territory’s future. The UK could not be expected to forever confront an ever-stronger PRC which sought to rectify what it saw, correctly, as a massive past injustice. Attempting to do so likely would have ended badly — and not just for Hong Kongers. The British people could have found themselves in a needless war with unpredictable but surely negative consequences. In contrast, it was possible, though certainly not likely, that the peaceful return would work out for Hong Kong’s and the UK’s benefit.

Thus, Margaret Thatcher probably did the best that she could. Arguably London should have provided all Hong Kongers with provisional British citizenship, though it would have been a major ask for the UK to absorb potentially millions of immigrants at once. In any event, the Johnson government has partially remedied this mistake with its willingness to take in upwards of three million people, if necessary. Other Western nations, including America, also should offer refuge for anyone seeking to leave.

Hong Kong has been one of the great showcases of the power of human creativity and productivity. Long judged the economically freest spot on earth, Hong Kong also protected civil liberties despite its lack of political democracy. But this unique experiment has been killed by the PRC. In time Hong Kong is likely to look like any other city in China, busy and prosperous, but unwilling to allow its people the freedom to speak or write freely.

Tragic though this outcome is, the worsening dictatorship cannot be blamed on Thatcher. And there was little she could have done to have saved China or Hong Kong. Moreover, there is good news: history rarely offers permanent verdicts. We have no idea what will follow Xi. Perhaps the pendulum will swing again, this time back toward the free society that Hong Kong once was.