In 1994, Susan Rice was the director of Africa affairs for the National Security Council during the Rwandan genocide. Rice allegedly said during a meeting that "if we use the word 'genocide' and are seen as doing nothing, what will be the effect on the November election?” (Rice says she doesn’t remember the quote.) The quote — unfairly or not — has been attached to Rice’s career ever since.

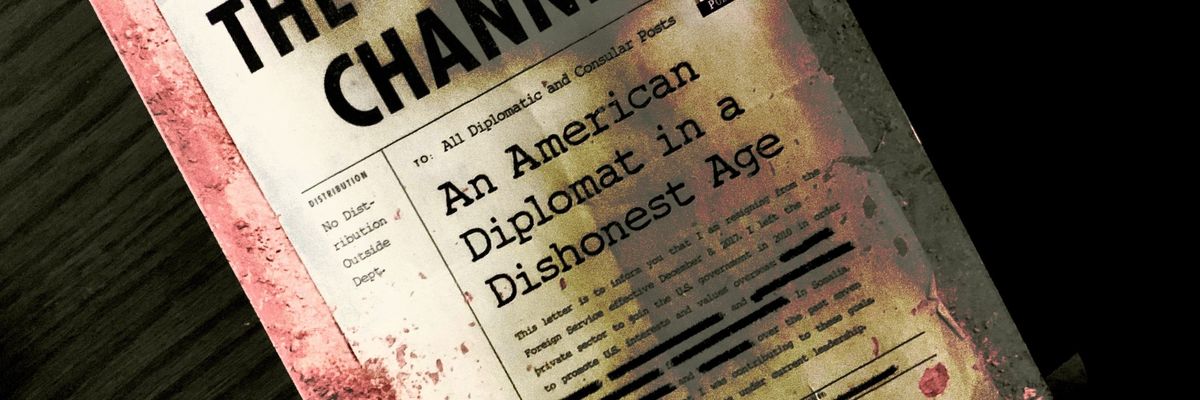

One implication of the Rwandan genocide is that the international community’s failure to protect civilians is a universal reference point for diplomats. Whispers about avoiding another embarrassing failure to protect civilians reverberates into every peacekeeping deployment. Preventing another Rwanda or Srebrenica has contributed to the support of strongmen who promise stability. Yet quiet diplomacy can have similar consequences, a lesson that is chronicled in Elizabeth Shackelford’s new book “The Dissent Channel.”

In 2013, Shackelford is a plucky diplomat who forgoes plum assignments to take a hardship posting as a political and consular officer at the American embassy in South Sudan. Shackelford arrives at the apex of an ostentatious nation-building project that is fueled by American diplomacy, Christianity, and celebrity. Shackelford dines with deranged generals that ride turtles and uses access to a pool for political gossip. The dust and sweat from Juba seep through the pages. But Shackelford becomes alarmed at the self-delusion that has infested the diplomatic community.

“South Sudan’s friends continued to take pains to reinforce a hopeful fallacy of progress and a government trying to do the right thing,” Shackelford writes. The U.S. Embassy edits a human rights report to remove a reference to how the government shot down a U.N. helicopter. After a woman working for the U.N. is dragged out of a car and has her head smashed against the road by government soldiers, the top U.N. diplomat in South Sudan, Hilde Johnson, suggests the victim was a problem anyway.

Corruption is rampant. “The friendly approach wasn’t working…it was unclear to me what influence we were trying to preserve,” Shackelford writes. It is little surprise when Shackelford wakes up on December 15 to the sound of gunfire. South Sudan’s war started. Ethnic cleansing began and never really ended.

A large section of the book details the unglamorous work of diplomacy. Shackelford finds that the American officials who choose bombastic radio call-signs like “James Bond” are a dud in a war. “Bond" was among the first to take an evacuation flight out of Juba. A crisis shows just how hollow our perception of toughness really is. Instead, Shackelford — codenamed Jackson — orchestrates evacuation flights for American citizens under the pounding Juba heat with a soundtrack of tank cannons and gunfire. She did it all with a broken foot.

But the book is most interesting when it details what happens after the evacuation mission ends. Shackelford deserves extraordinary credit for her honest depiction of the mental anguish that war imparts on non-combatants. The nightmares. The anger. The regret. It’s silly that societal stigmas cause many to hide the mental residue of war.

Most diplomats daydream about writing blunt assessments of their colleagues, but Shackelford actually follows through. Shackelford is most critical of Susan Rice, who became Obama’s national security adviser. “Susan Rice had made clear her continued partiality toward the government,” Shackelford writes.

She describes how Rice blocked an arms embargo on South Sudan at the U.N. Security Council, even when Russia and China looked persuadable. History will remember Rice as being unfairly tarred for her role in the Benghazi attacks and for an inappropriate comment during the Rwandan genocide. But Rice’s untold legacy will be America’s dreadful policy in South Sudan. It is easy to trace how Chinese weapons sold to South Sudan’s government that would have been banned under an arms embargo almost certainly ended up killing civilians. “Given Kiir’s bad acts, Rice’s position was indefensible,” Shackelford writes, referring to South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir Mayardit.

One of the most interesting characters in Shackelford’s book is the American ambassador to South Sudan, Susan Page. Shackelford respects Page. There are flashes when Page is three steps ahead of everyone else. Page knows to “feed the beast” of Washington’s endless need for information during the killing days of 2013 in order to keep control of the American response.

“Washington didn’t understand the situation and it didn’t understand the players like Page did,” Shackelford says. At the same time, Shackelford is also critical of the American ambassador. “Page had not been tough enough on the government in the lead-up to the war,” Shackelford says.

“The Dissent Channel” is an insight into how the civil service is a juggling act between principle and practicality. A stereotype is that junior officials are more idealistic while more senior diplomats have the rough edges sanded down after years of service. Would Page do anything differently?

Shackelford is haunted by the American policy in South Sudan and begins to organize a dissent cable — the State Department’s system of internally objecting to U.S. actions. Other diplomats sign on. The dissent cable criticizes the American empty threats on South Sudan, calls for sanctions on the country’s leaders, and recommends an arms embargo on the country. “Our close relationship with the South Sudanese government had come at a tremendous cost, and our commitment to the country’s leaders had not been reciprocated,” Shackelford says.

Critics of America’s policy in South Sudan will be pleased to read Shackelford’s account of how widespread the dissatisfaction was inside the State Department. But it brings up the painful question of how a position that had so much support was still ignored. Shackelford’s dissent cable is answered with a five-page letter that neatly dismisses the criticism. “The Dissent Channel was the last resort. I’d taken it, and it didn’t matter,” Shackelford concludes.

“The Dissent Channel” is in part a 294-page theory about why the cable was ignored. Shackelford argues that America doesn’t match its human rights rhetoric with action. It’s impossible to know what would have happened in South Sudan if the dissent cable was followed. But we know what happens when America dithers to a government committing ethnic cleansing. Approximately 400,000 people died in South Sudan’s civil war and the conflict continues today.

President Obama’s foreign policy legacy will be judged on a curve because of the shambolic administration that has followed. But Shackelford’s book is part of the growing criticism from liberal civil servants in the Obama years who remind us that quiet diplomacy has its flaws and inaction has consequences.