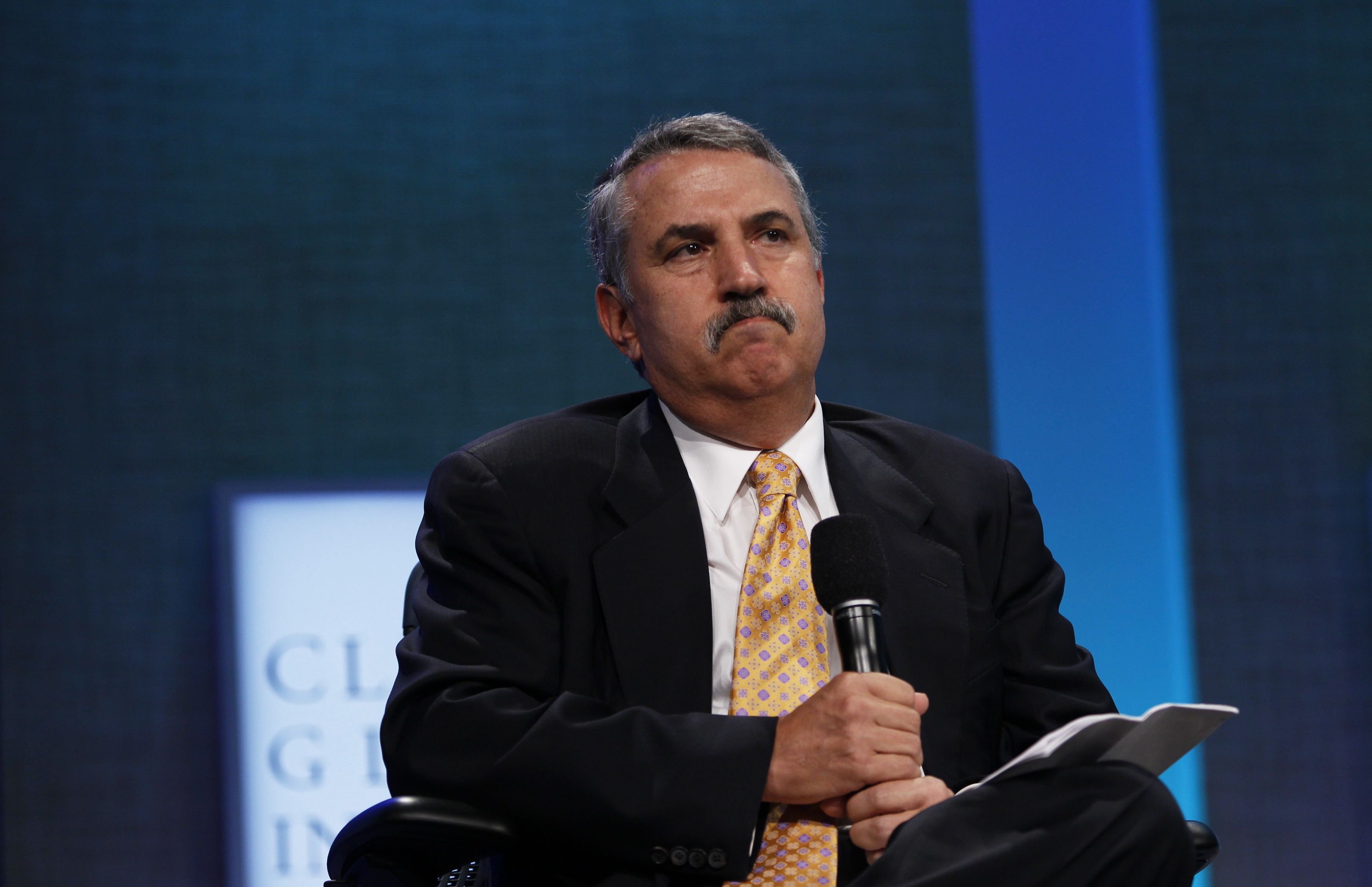

An iconic New York Times columnist, Thomas Friedman, has just been squired around the Middle East by the commander of Central Command, the U.S. military headquarters for operations in the Middle East, Persian Gulf and North Africa.

Now, don’t get me wrong, the military and American journalists have cultivated symbiotic relations since the Civil War. It’s in the nature of things. The press needs access, and the military needs public and congressional support. Quality time shared by the top U.S.military officer for this volatile region and the top foreign affairs columnist for the nation’s top broadsheet makes sense.

Among their whistlestops were U.S. installations in Syria. About 900 American troops are there, distributed in penny packets among seven bases. Some of these protect oil fields that supply U.S.-backed Kurdish authorities; others are in the far northeast, where they assist Kurdish units, help secure and supply the cluster of camps that house ISIS prisoners and their families and continue to hunt ISIS fighters; and still others in the southeast, at a road junction where the Iraqi, Syrian and Jordanian borders meet. This base was set up to interdict Iranian-backed forces attempting to entrench themselves in Syria and transport supplies to Lebanon.

In Friedman’s recap of this visit, he explained that the importance of these U.S. deployments lay in the need to fight the terrorists over there so we would not have to fight them over here.

Let’s say, for the moment, that there are several other rationales for maintaining troops in Syria. Iran, for example, does seek to use Syria as a land corridor to Lebanon and the Israeli-Syrian border, from which it can carry the fight to its enemy. Iran is 1,200 kilometers from Israel, so if it wants to reach out and touch someone without using ballistic missiles, it needs to be on Israel’s borders. Rendering this a bit more difficult than it might otherwise be makes a regional blow-up marginally less likely.

Maintaining a garrison at the oil fields is meant to secure them from capture by either ISIS or the Assad regime, against which the U.S. maintains heavy sanctions. Reserving the oil for use by Kurds, both for sale and consumption, reflects a longstanding policy that favors Kurdish autonomy in Syria. This policy preference, which owes in part to a romanticized image of Kurds as daring fighters fending off terrorist hordes to spare the U.S. an onerous burden, also dictates the use of U.S. forces in northeast Syria as a tripwire deterrent against Turkish attempts to suppress Syrian Kurds.

For many members of Congress, they seem to be something like T.E. Lawrence’s Bedouin insurgents in World War I, or U.S.-backed Montagnard guerillas in the Vietnam War. For them, abandoning the Kurds to the tender mercies of Turkey, or compelling them to seek protection from the Assad government, would be immoral and shred America’s reputation as a reliable ally. (See under: Munich.) Trump, marching to the beat of a different drum, pointed out that the Kurds “didn’t help us in the second world war, they didn’t help us with Normandy as an example… .”

The U.S. role in helping local forces and NGOs manage the ISIS detention centers and refugee camps as well as the slow process of the repatriation of Iraqi detainees, is meant to contribute to Iraqi stability, in which the U.S. has a stake. The fact that these bases are magnets for attack by Iran-backed militias is arguably a factor that outweighs any of these other considerations.

One can have this or that view on the validity of these rationales or the salience of these objectives for core U.S. strategic interests. If the Turks and their radical Arab militias rip into the Kurds to get at the PKK, as they have done twice already, U.S. strategic interest is unlikely to suffer very much. If ISIS fighters escape the camps in Syria, Iraqi forces with U.S. help could probably limit the threat to Iraqi stability. The U.S. installation at al-Tanf in the southeast can be bypassed by Iran-backed militias via an Assad-controlled base at al bu-Kamal, a bit northeast of al-Tanf, so the U.S. base there might have outlived its usefulness.

Of course, on any given day there are about 30,000 U.S. military personnel in the region, as there have been for decades, so 900 isn’t a particularly impressive number. It’s a good example of limited interests served by a commensurately limited commitment. Whether to stay or go comes down to a narrow judgment call.

But of all the factors to consider there is one that does not merit concern: the idea of fighting them over there so we don’t have to fight them over here. It’s a vacuous meme trotted out to defend the controversial commitment and use of forward deployed forces and creation of distant security perimeters.

If you were a Briton in September 1939 facing the German juggernaut, Friedman’s old chestnut would have been pretty compelling. But since World War II, its specific gravity has dissipated. During the Vietnam War, Lyndon Johnson defended the U.S. commitment by asserting that the countries of southeast Asia were like a row of dominos; if south Vietnam were to fall, it would tip over all its neighbors until all of Asia was communist. The problem, he explained, was that “Everything that happens in this world affects us because pretty soon it gets on our doorstep.”

Anyone who was politically sentient at the time was bombarded by Friedman’s repurposed, shopworn epigram. Yet, the dominos never fell following the U.S. pullout and the collapse of South Vietnam; in the fullness of time, we never had to fight them over here and the only stuff on our doorstep are Amazon boxes.

President George W. Bush, in a major speech at the 89th Veterans of Foreign Wars convention in 2007, declared “Our strategy is this: we will fight them over there so we do not have to face them in the United States of America.” But the insurgency in Iraq was created by the 2003 U.S. invasion, which decapitated the regime and destroyed the capacity of the state to manage the country’s affairs, while unleashing Shi’a power and Iranian influence. This ignited a brutal Sunni insurgency carried out, in part, by tens of thousands of soldiers the U.S. threw out of their barracks and left to fend for themselves in an anarchic and violent environment.

The ideology and strategy of both Shi’a and Sunni insurgents had nothing to do with al-Qaida, let alone engaging SWAT teams in Dallas, or stealing our lawn furniture, as one of my former counterterrorism colleagues put it. Their concerns were local. Al-Qaida sought to attack the great power, the “far enemy,” that underpinned the “near enemy,” namely the conservative monarchy ruling Arabia. Al-Qaida in Iraq, ISIS, the Mahdi Army and Iran-backed militias fought a battle for power on their turf and against an occupying army, not an expeditionary war against the U.S. homeland.

The mayhem, moreover, had nothing to do with 9/11. The fact that there was never another al-Qaida attack was not because the U.S. invaded Iraq; it was because of al-Qaida’s inability to follow up on its spectacular success. And that was a function of the loss of its support network in the U.S., the decimation of its top tier, and the swift tightening of security at U.S. borders.

Now we are told once again that U.S. troops have to be somewhere else to prevent fighters operating in that space from coming to the United States and waging war here. The designated enemy in this case is the Islamic State, an organization that has inspired or arranged successful attacks in Europe but not in the U.S. It would be foolish to assume that no one in the organization dreams of murdering Americans in their beds. But they lack the capacity to do so and, more importantly, have urgent local goals that soak up resources, planning and organizational capacity, and face serious local constraints.

There is a legitimate debate about the presence of U.S. forces in Syria. But it should be premised on the value of the real things at stake and the cost of protecting those stakes. It should not be distorted by old canards intended to inflate threats to the American homeland.