In his memoir "Chasing the Light," director Oliver Stone talks about America's angst over Vietnam:

"We were so proud, and then, when we couldn't achieve victory, we had to lie like we all do when we deny what we know is true — that we lost, and lost big-time, and all those technology-loving Pentagon warriors were at last revealed as failures, and those determined little Vietnamese had licked us."

Then why did we not try to avoid the same fate time and again?

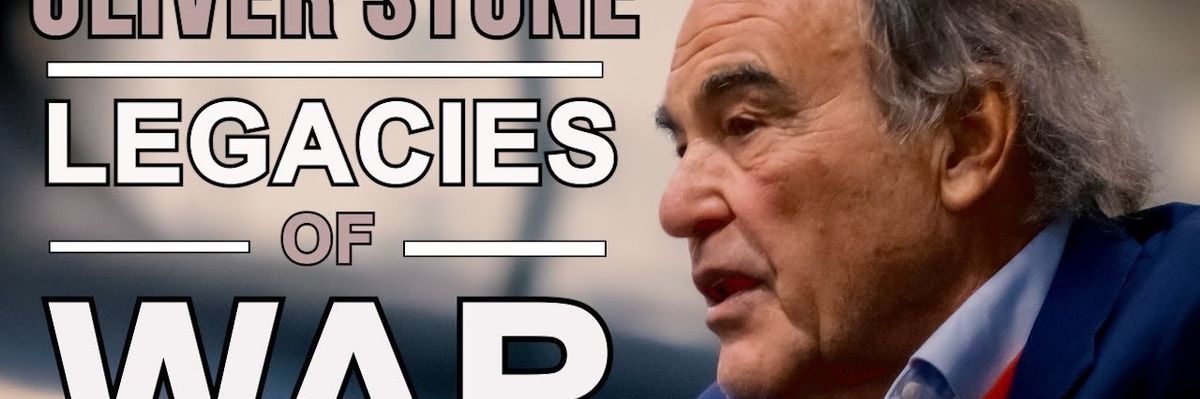

In early December, the Quincy Institute, in concert with the Center for War and Society (San Diego State University), hosted Stone at the iconic USS Midway Museum to commemorate, in part, the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. Gregory Daddis, director of the Center for War and Society and professor of military studies, got a chance to ask Stone not only about his own service as an Army infantryman (which later inspired his 1987 film "Platoon"), but about his own frustrations with the cyclical nature of American war-making, right up to Russia-gate, and today's current conflicts.

Watch below:

- Prolonging the Ukraine war is flirting with nuclear disaster ›

- Oliver Stone: World War III may be inevitable ›