“[T]herefore you may rest assured that if the Nicaraguan activities were brought to light, they would furnish one of the largest scandals in the history of the country.”

Such was the concluding line of a letter from Marine Corps Sergeant Harry Boyle to Idaho Senator William Borah on April 23, 1930. Boyle’s warning was not merely an artifact of a bygone intervention, but a caution against imperial hubris — one newly relevant in the wake of “Operation Absolute Resolve" in Venezuela.

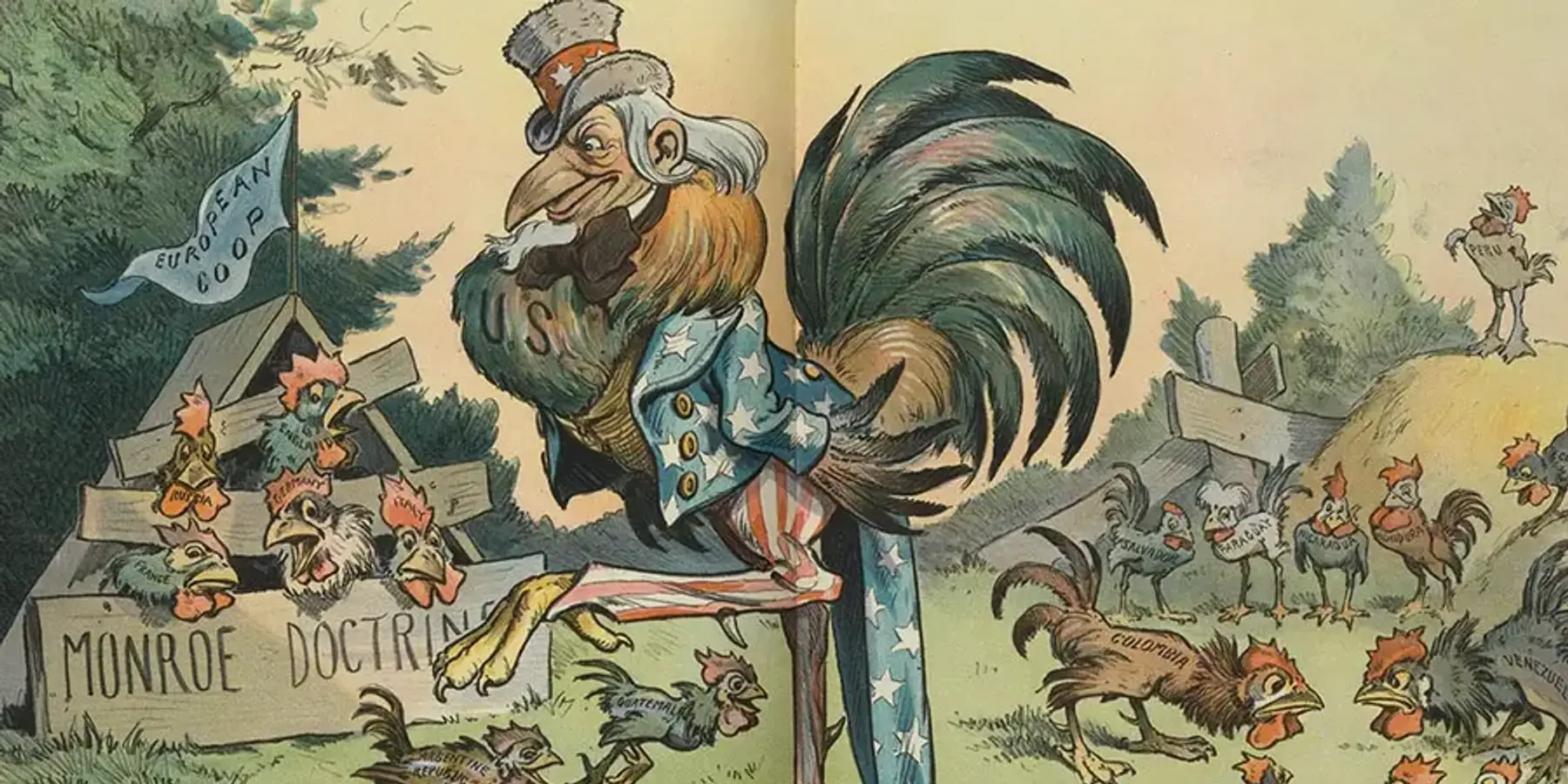

The Trump administration has amplified the afterglow of its tactical success with renewed assertions of hemispheric hegemony through a nostalgic and often ahistorical reading of the Monroe Doctrine. Despite the administration’s enthusiasm for old-fashioned hemispheric imperialism, the historical record ought to caution for restraint, not revisionism.

When modern American officials invoke the Monroe Doctrine, they often do so with a confidence that suggests its meaning is settled and its record vindicated. Historically, the doctrine — both in meaning and in application — was far more contested than modern enthusiasts let on. Indeed, the high-water mark of American imperialism in the Caribbean exposed the high costs and meager returns of micromanaging neighboring states.

Critics of the president’s muscular approach to Latin America have often cited the recent Middle Eastern record of U.S. interventionism as a warning. While such comparisons have limits, the Latin American record offers little reassurance of its own. For all the confidence of its modern champions, the meaning and application of the Monroe Doctrine was never fixed, codified, or uncontested.

The apex of American military hegemony in the Caribbean basin, often justified under the auspices of the Monroe Doctrine, came during the so-called Banana Wars. From the 1890s through the early 1930s, U.S. forces intervened in seven countries, including decades-long occupations of Haiti and Nicaragua. Over this period, successive presidents used military force to protect American agricultural interests from nationalization and labor unrest and to prevent Latin American debt defaults that policymakers feared might invite European intervention.

Despite new waves of wistfulness in some corners of the MAGA movement, such interventions were not uniformly popular on Capitol Hill or in the general populace, and by the mid-1920s, the tide had turned against such acts of naked imperialism. Bolstered by the anguish of World War I, a diverse set of domestic voices, religious pacifists on one end, to xenophobic populists on the other, viewed military action in the Caribbean as wasteful, pointless, and morally abhorrent.

A consistent voice of opposition to hemispheric imperialism was Senator Borah. Belying the stereotypes often attributed to opponents of American imperialism, Borah opposed American intervention in Nicaragua because he was a sovereigntist who recognized the limits of American power.

“Under the Monroe Doctrine, we have no right to interfere with the internal concerns of any Central American country or the integrity of any government in Central America,” he said. Borah further argued and elaborated that the “imperialist, whatever form his activities may take — oil or mahogany or bonds — appeals to the Monroe doctrine to protect and justify his course.”

In contrast to today’s supine Congress, opposition from senators such as Borah, bolstered by significant coordination with domestic and Latin American activists, achieved substantive policy change. Opposition in Congress, coupled with the futility of putting down a rebellion in Nicaragua, in the words of scholar Sean A Mirski, “reinforced Washington’s commitment to ending its interventionist policies.”

Starting with Herbert Hoover and his vaunted goodwill tour of Latin America and finishing with Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor policy, the United States eventually learned the lesson that military intervention in its near abroad was as foolish as intervening in Europe and course-corrected towards a policy of mutual respect and economic engagement. Lost amid today’s chest-thumping is the fact that many who carried out America’s interventionist policies later came to regard them as blunders. We would be wise to listen to their experience rather than baseless nostalgia.

Supporters of the “Donroe Doctrine” are right about one thing: great powers, including the United States, naturally have security concerns in their immediate neighborhoods. Certain redlines remain in the current year as they did in 1962 when the Soviet Union emplaced strategic weapons in Cuba. However, in our era of absurd threat inflation, the administration and its supporters have elevated drug trafficking, illegal migration, and economic competition to existential threats rather than manageable issues.

Admittedly, the administration is currently pursuing a pragmatic, if somewhat puzzling, track in a post-Maduro Venezuela by proffering Delcy Rodríguez as a successor. Yet, as it has been said, appetite comes with eating. So long as the Trump administration maintains maximalist aims in Venezuela and an ambitious, unrestrained vision for its role in the Western Hemisphere, it will continue to create and respond to incentives for unnecessary and unproductive entanglement.

It would be wise for the administration to resist a nostalgia based foreign policy. Those who carried it out made their opinions clear: imperialism, even in the Western Hemisphere, was a blunder.

- When Trump's big Venezuela oil grab runs smack into reality ›

- Trump's sphere of influence gambit is sloppy, self-sabotage ›