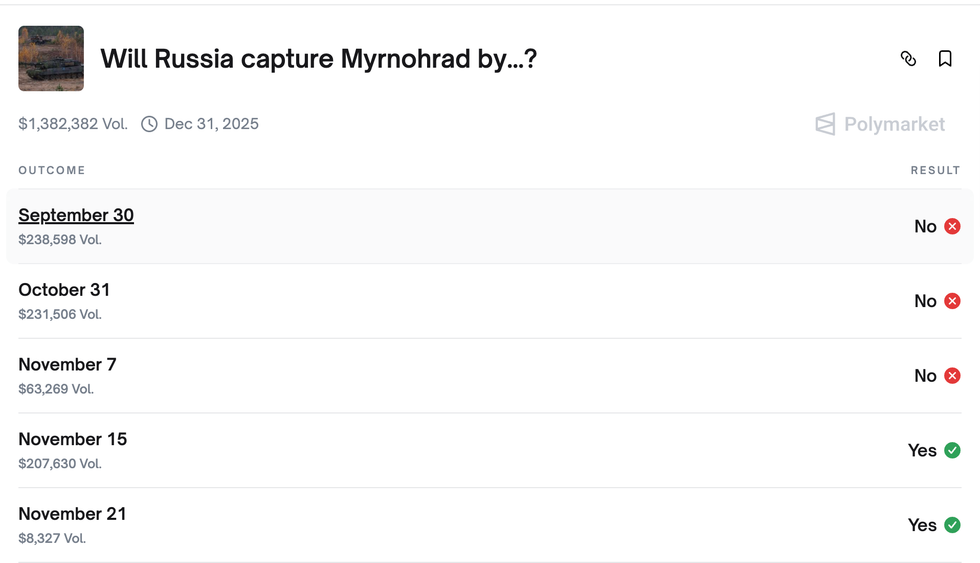

On November 15, as Russian forces were advancing on the outskirts of the town of Myrnohrad in eastern Ukraine, retail investors placed risky bets in real time on the battle using Polymarket, a gambling platform that allows users to bet on predictive markets surrounding world events. If Russia took the city by nightfall — an event that seemed exceedingly unlikely to most observers — a handful of retail investors stood to earn a profit of as much as 33,000% on the battle from the comfort of their homes.

When nightfall came, these longshot gamblers miraculously won big, though not because Russia took the town (as of writing, Ukraine is still fighting for Myrnohrad). Instead, it was because of an apparent intervention by a staffer at the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), a D.C.-based think tank that produces daily interactive maps of the conflict in Ukraine that Polymarket often relies on to determine the outcome of bets placed on the war.

According to tech outlet 404 Media, just before the market was resolved, someone at ISW edited its map to show that Russia had taken control of a key intersection in the town, despite the lack of indications that Russia had made any such advance. After Polymarket had paid out the winners of the bet, ISW’s edit mysteriously disappeared by the following morning.

Without making any reference to online gambling, or Polymarket, ISW issued a statement on November 17 asserting that the misleading edit had occurred without approval. “It has come to ISW’s attention that an unauthorized and unapproved edit to the interactive map of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was made on the night of November 15-16 EST. The unauthorized edit was removed before the day’s normal workflow began on November 16 and did not affect ISW mapping on that or any subsequent day.”

On November 18, ISW quietly removed the name of one of its Geospatial Researchers as a creator of the daily Ukraine maps published by ISW and took his name off the website. A source with knowledge of the incident indicated the staffer had been fired. ISW did not respond to multiple requests for comment and did not confirm that there had been an internal investigation or that anyone had been fired.

Polymarket users were incensed by the apparent fraud. One user told RS that ISW “definitely lost their reputation” and that “some people have begun to treat such markets more skeptically.” Users had put $1.3 million into the market betting on whether Russia would take Myrnohrad. Similar markets for battles in Ukraine have reached as much as $5 million in the past.

When Polymarket users raised the issue on X, some did not feign empathy for the war gamblers. “I hope you lost a lot of money because of this. Betting on war and destruction is ethically indefensible and morally reprehensible,” one account wrote.

Online gambling sites like Polymarket and Kalshi have exploded in popularity this year, raking in nearly $10 billion combined just last month while allowing users to gamble on, for example, when Israel will strike Gaza or when Trump announces new strikes on boats off the coast of Venezuela. Vietnam War veteran and author Tim O’Brien once wrote, “War is nasty; war is fun. War is thrilling; war is drudgery.” But today, war is also a casino.

“This is like a bet you really wanna lose,” one Polymarket user joked before betting that nuclear weapons will detonate before the new year. “Kinda strange lol.” If a nuclear war does break out, another user stands to make well over $100,000.

But with a flood of markets and no regulation, prediction markets are also ripe for abuse by insiders with access to non-public information. Taylor Lorenz, a technology journalist and author of the User Mag newsletter, explained to RS in a phone interview that prediction markets are especially vulnerable to manipulation by bad actors. “In this case, this person may have moved a war map, but you could easily see how someone could pay someone to incite or escalate a conflict that coincides with a bet that they played,” said Lorenz.

Of course, ISW never asked to be used by Polymarket. The think tank’s apparent objective is for its trusted maps to be used by lawmakers, the military, and prestigious media outlets like the New York Times — not terminally-online war gamblers willing to risk their savings on the Russian offensive moving a half-mile west.

And yet, this incident forced ISW to come to terms with this brave new world of prediction markets. The think tank told 404 Media that “ISW has become aware that some organizations and individuals are promoting betting on the course of the war in Ukraine and that ISW’s maps are being used to adjudicate that betting. ISW strongly disapproves of such activities and strenuously objects to the use of our maps for such purposes, for which we emphatically do not give consent.”

Legal repercussions for insider trading on prediction markets are “virtually non-existent,” according to Forbes contributor Boaz Sobrado. Prediction markets are regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission which does not address insider trading in prediction markets.

It’s unclear if there were other incidents in which the ISW staffer influenced maps for personal profit, but many in the notoriously skeptical Polymarket crowd have pointed to other instances to cry foul play. For instance, they point to an ISW map which showed that Russia had taken a railway in the Ukrainian city of Kupiansk on October 29 just ahead of a market resolution. Other maps by competitors like Deep State and Liveuamap did not show at that time that Russia had made such advances into Kupiansk. Currently, there is still intense fighting around the railway.

Of course, in the fog of war, it is especially difficult to know precisely where the frontlines are, and many Polymarket gamblers live by the rule, “If I win, skill. If I lose, rigged.”