Surfacing a long-dormant intra-party conflict, the Friedenskreise (peace circles) within the Social Democratic Party of Germany has published a “Manifesto on Securing Peace in Europe” in a stark challenge to the rearmament line taken by the SPD leaders governing in coalition with the conservative CDU-CSU under Chancellor Friedrich Merz.

Although the Manifesto clearly does not have broad support in the SPD, the party’s leader, Deputy Chancellor and Finance Minister Lars Klingbeil, won only 64% support from the June 28-29 party conference for his performance so far, a much weaker endorsement than anticipated. The views of the party’s peace camp may be part of the explanation.

Why it matters

The release of the Manifesto poses a challenge to the party’s leadership that could weaken the governing coalition. Polls indicate that Germany’s Social Democratic Party commands only about 15% of public support. It remains, however, indispensable to the parliamentary majority government headed by Friedrich Merz and the CDU-CSU parties (Christian Democratic Union of Germany and Christian Social Union in Bavaria). The new leadership of SPD wants to turn the page on the Olaf Scholz era and sees its role in the Merz government as an opportunity to rebuild its electoral fortunes after its miserable 16% showing in the February elections.

To date, accommodation of CDU-CSU on a range of issues has not helped SPD’s standing with voters.

Unfortunately for Merz, his own hold on power requires the SPD not to lose much more ground. After the resounding defeat of SPD Chancellor Olaf Scholz, the much younger Klingbeil rose to party leadership and, as Deputy Chancellor and Finance Minister, supports Merz’s stance on Ukraine and the defense buildup. Important backing comes from the SPD Defense Minister Boris Pistorius.

A heretofore timid and cowed minority of SPD politicians hold onto the preference, deeply embedded in the strategic culture of post-World War II Germany, for conciliation over confrontation in resolving international crises. Unease about the prevailing stance on Ukraine may be part of the weak voter support for the SPD. Merz has played up the idea of a Russian threat to NATO as early as 2029 if Ukraine is defeated, and has built considerable public support for rearmament based on these forecasts.

The unyielding stance on the war in Ukraine draws together the parliamentary majority held by CDU-CSU and SPD, as well as the Greens, while the parliamentary opposition consists of the AfD and the Linke (left) party, both of which question continued support for Ukraine absent any diplomatic initiative. The German policy on Ukraine appears to hinge on the hope that a prolonged conflict will ultimately compel Russia to retreat from its war aims and accept a compromise acceptable to Ukraine’s leadership.

This stance, framed in moralistic and principled terms equating compromise with dishonorable appeasement, is highly resistant to any revision. The insistence on staying the course seems to be rooted also in optimism that a successor to President Trump will return the U.S. to its former role as guarantor of European security and reliable foe of Russian ambitions.

The Manifesto

The Manifesto marks a revival of the traditional foreign policy course set by Willy Brandt beginning in the late 1960s, credited in the minds of many SPD members and other Germans with producing the peaceful dissolution of the USSR and the reunification of Germany.

The two leaders of the peace camp who produced the Manifesto are Rolf Mützenich, leader of the party’s Bundestag faction until February, and Ralf Stegner, a member of the SPD Executive Committee until recently. The 100 signatories of the Manifesto include a former party chairman, several former ministers, and historian Peter Brandt, son of the former Chancellor.

The release of the Manifesto marks a departure for these signatories, most of whom supported Scholz’s Zeitenwende of 2022, which boosted aid to Ukraine and defense outlays more generally.

The authors charge that the party and the coalition are seeking peace and security by preparing for war rather than, as the authors advocate, pursuing the same aims along with, rather than against, Russia. They concede that Germany should build up its defense readiness (Verteidungsfähigkeit), but they invoke the Helsinki Final Act concept of collective security, which they say produced valuable arms control agreements and enabled the reunification of Germany.

They also call for de-escalation and mutual confidence building to accompany a carefully calibrated rearmament framed solely in a defensive mode and for supporting German and European industrial development.

The signers also endorse a European diplomatic strategy to end the war in Ukraine and oppose the stationing of U.S. medium-range missiles in Germany.

Reception of this action by SPD mainstream has been cold. The SPD defense minister, Boris Pistorius, by far the most popular SPD politician, accused the signatories of failing to face reality and exploiting the public’s desire for peace.

The disappointing showing for Klingbeil at the party conference may reflect misgivings within the party about his unreserved support for what many see as excessive bellicosity and fear-mongering on the part of Merz. The timing of the peace faction’s Manifesto release suggests they hoped to open a breach in the party ranks.

- Germany gets a new antiwar party, this time on the left ›

- As Germany lurches left, its foreign policy may go right ›

- Anti-war sentiment has Germany's major parties on the run ›

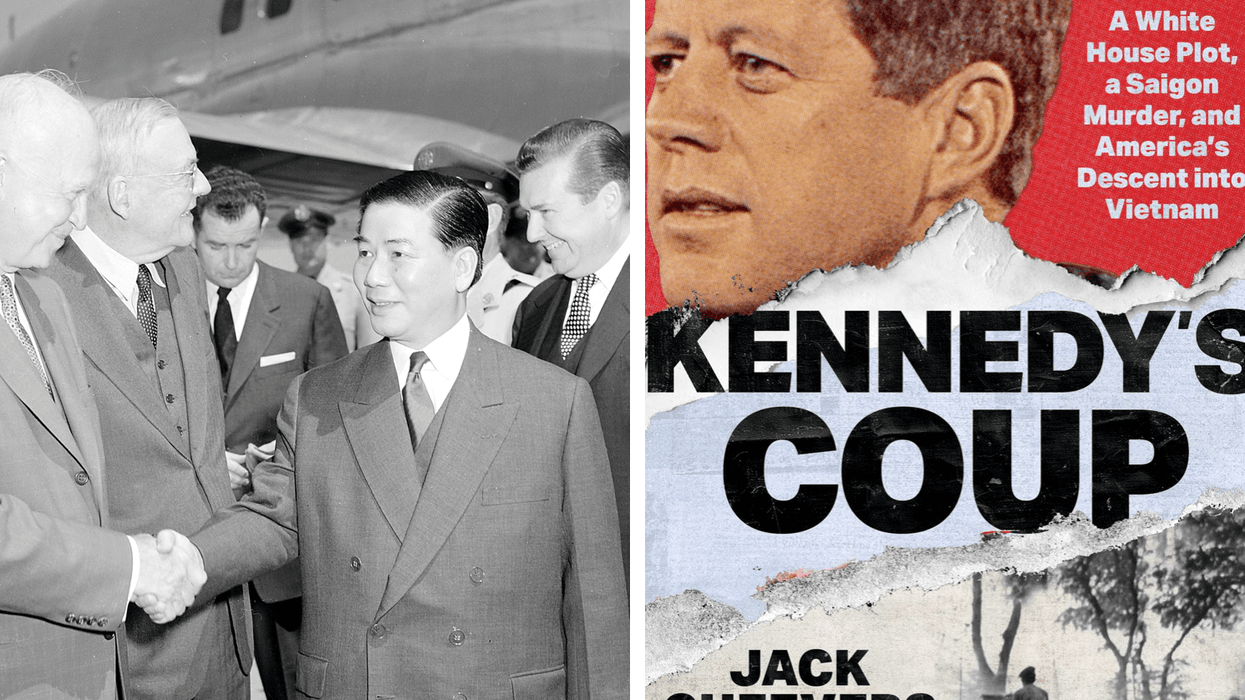

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)