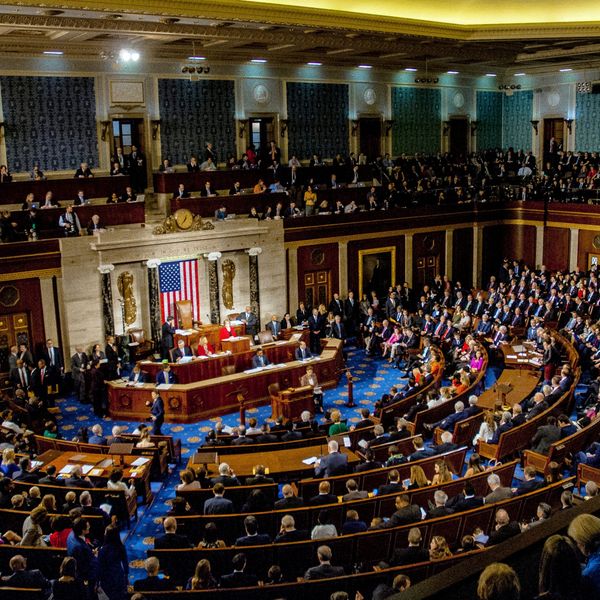

What if the chair of the powerful Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the committee that oversees legislation impacting war powers, treaties, troop deployments, and military aid, was illegally acting as a foreign agent of Egypt, one of the biggest recipients of U.S. aid and military sales?

That scenario is exactly what the Department of Justice alleged last month when it accused Sen. Bob Menendez (D—NJ) of using his influence to increase U.S.-taxpayer funded aid to Egypt in exchange for gold bars, a Mercedes and stacks of cash.

The Justice Department and Menendez are making history. This is the first time a sitting U.S. senator has been accused of violating the Foreign Agents Registration Act (or FARA), a law that prohibits Members of Congress from acting as an agent of a foreign principal.

The Justice Department’s FARA investigations into a high profile politician, think tank president and hip hop star sends a clear message that no one is above the law, says a new video by the Quincy Institute’s Senior Video Producer Khody Akhavi and Democratizing Foreign Policy Program Director Ben Freeman.

- Menendez's New Jersey: Global power hidden in plain sight ›

- Menendez took bribes to help Egypt get weapons: Prosecutors ›

- Foreign bribery has a long history in Congress | Responsible Statecraft ›