The proof of genuine statesmanship is to know how and when to stop. This is what distinguished the great 19th century statesmen, Bismarck, Talleyrand and Metternich, from their 20th century successors.

Recent events involving Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin’s short lived mutiny in Russia and its aftermath are obscure and open to interpretation. News and speculation continue to churn. Fortunately, it is not essential to know exactly who did what, for whatever reason, and what guided their actions.

We need to spot what possibilities, hitherto closed, open up. When the major pieces on the chessboard are moved, the time can be ripe for the decisive move.

In other words, what looked unlikely just a few days ago may now be within reach or at least worth a try: End hostilities; maybe even go for peace.

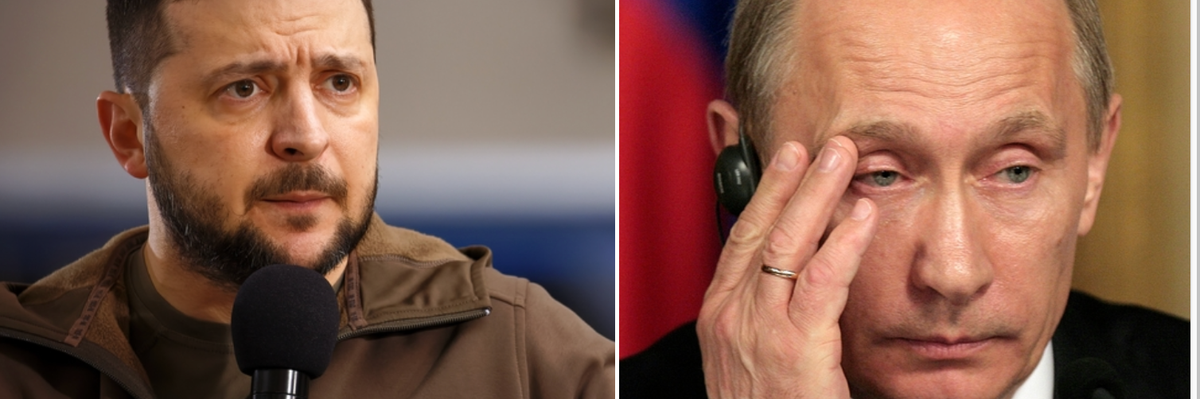

Russian President Vladimir Putin almost certainly thought his grip on power was rock solid when he started what he called a “special military operation” in Ukraine last year. The Wagner Group’s participation was probably intended as some kind of “divide and rule” strategy, affording him an alternative to the military. It is a well-known tactic often seen in authoritarian states.

The wish to keep casualties at a minimum for “ordinary” Russians led to a big role for the Wagner group, setting the stage for a competition and ultimately a confrontation between Prigozhin and the top brass of the Russian army. It started months ago when Prigozhin began criticizing the generals. As that criticism intensified, Putin had no choice but to do what he didn’t want to do: choose. It was totally contrary to his original intentions — to play one group against the other.

In his view, securing his grip on power was and remains priority number one. The question is whether he can do so with the war in Ukraine ongoing? The war was the matchstick that started the fire, so ending it may appear to be the best of a long list of unsavory options. He can then devote his full attention to domestic issues.

Continue the war, and he is trapped, making himself more dependent on the top brass whether the incumbent top generals stay or are replaced. Putin came of age in the Soviet Union and can hardly forget that an accusation of Bonapartism — referring to the replacement of the leaders of the French Revolution by the relatively obscure Gen. Napoleon Bonaparte who went on to establish himself as Emperor — marked the accused for either a Siberian gulag or execution.

The alternative is to double down on the “special military operation,” mobilizing more troops or resorting to weapons hitherto ruled out as too risky or provocative. None of these options look palatable.

China has offered to mediate. What are the conclusions/lessons drawn from the latest developments by its leadership? In the first place, there is now a risk that Putin’s political system may collapse. Such an outcome would be highly unwelcome, as the government in Beijing has been conveying to its people that Russia’s is a “good” system with which China can cooperate. Could such an event take place in China? This question is not attractive to the Chinese Communist Party, to say the least.

Similarly, Russian military escalation risks spinning out of control in ways that could further threaten China’s increasingly fraught relations with Europe and thus threaten its own stability, the preservation of which is the CCP’s top priority. And, since the outset of the Ukraine war, Beijing has repeatedly made clear it opposes any resort to nuclear weapons.

China may well conclude that the Wagner rebellion makes ending the war more important than ever – for China.

In the wake of the revolt, the United States and Europe may be tempted to see an opportunity to escalate their military assistance to Ukraine with the aim of expelling Russian forces from all of Ukraine in the most humiliating way. This temptation, however, should be resisted. Russia will still be there, with or without Putin, with one of the two world’s largest nuclear arsenals. Like it or not, it’s a power the West has to live with.

President Biden should take a page out of President George H. Bush’s playbook in the First Gulf War when he was urged to topple President Saddam Hussein in Iraq, saying that his coalition and the UN mandate was to liberate Kuwait. Once that mandate was fulfilled, he stopped.

Ukraine may realize that a continuation of the war, especially if Russia steps up its military capabilities, will further devastate the country even if Kiev’s most recent and much-anticipated counter-offensive, which has not yet made much progress, eventually achieves greater success. The price may be too high. So, too, the risk of Russian escalation.

Some in Ukraine may have felt encouraged by the Wagner revolt, underlining the fragility of Russia’s military command, if not the regime itself. But even if Putin was ousted, what would be the likelihood that a more reasonable and less nationalistic leadership would emerge?

No one knows for certain how long the currently robust levels of U.S. and European commitment to Ukraine will last. The 2024 U.S. election may be won by a candidate with other ideas about supporting Ukraine than the Biden administration.

For the moment, none of the major actors in this war appear to favor stopping war and making peace. But for all of them, the alternatives may be worse.