While the Twitter files revelations today have shocked some about the U.S. government’s role in advancing and enforcing the Russian influence/meddling narrative on private social media platforms beginning in 2017, they are part of a long, evolving history of covert and overt manipulation by Washington to promote support for its foreign policy goals.

In order to bring about and ensure consensus around what amounted to nearly 80 years of a U.S.-led world order, we know now that the federal government has used tools of both hard and soft power within the “marketplace of ideas” against its own citizens, undermining the very democratic ideals it was constitutionally bound to protect.

This — what we will call the information state — began really with American participation in the Great War. Upon entering World War I, Woodrow Wilson knew it was critical to rally public opinion behind the conflict. To achieve this end, the president created the Committee for Public Information (CPI) via executive order and appointed political ally and former investigative journalist George Creel to lead it.

According to historian John Maxwell Hamilton, the CPI "shot propaganda through every capillary in the American bloodstream." Creel's organization proliferated pro-Allied and xenophobic anti-German messaging through its press releases, the covert subsidizing of newspapers, public speakers, and even church sermons. The CPI pressured American media to censor news and coordinated with other government agencies, including the Postal Service, to restrict dissident content. In addition to boosting the U.S. government's position on the war, the CPI amplified the domestic threat of German agents, framed calls for a negotiated peace as "spy talk," and pressured newspaper editors who considered running articles critical of the war into forgoing publication.

Creel's CPI was paralleled in its efforts by a similar campaign by the British government. Even before the United States formally entered the World War I, British intelligence worked to move American public opinion towards the Triple Entente. British agents could exploit their connections in American media and government to plant stories that exposed the presence of German intelligence activities on American soil and ensured that friendly press outlets spread the word. British intelligence also worked to cultivate moral support for the war by presenting as an inevitable clash of civilizations. These spies also used their connections to flag specific stories for censorship, passing them off to American officials for enforcement under the Sedition Act.

The American public learned about these British and American propaganda campaigns through a series of self-congratulatory memoirs and postwar investigations. American and British propagandists were bragging about their exploits even before the war ended. In 1918, Gilbert Parker, a Canadian-born, British propagandist, asserted in an essay in Harper's about his efforts: "the scope of my department was very extensive and its activities widely ranged" and supplied three hundred and sixty newspapers to the smaller States […] we utilized the friendly services and assistance of confidential friends [and] with influential and eminent people of every profession in the United States."

Not to be outdone, in his own How We Advertised America, published in 1920, George Creel boasted that the CPI's efforts "reached deep into every American community" and that there "was no part of the great war machinery that we did not touch, no medium of appeal that we did not employ." Creel viewed his charge as necessary, for, in his view, "[w]ith the existence of democracy itself at stake, there was no time to think about the details of democracy."

The public and journalistic response to these revelations was one of transpartisan outrage. Media outlets across the political spectrum, including those that had previously supported the war effort, recoiled at the idea that the American and British governments had sustained efforts to guide public opinion and control dissent. The Nation, an erstwhile progressive supporter of American involvement in the war, came to view the conflict as providing the government with previously "undreamed of ways of fortifying their control over the masses of the people." The Freeman, a classically liberal magazine, called these efforts "a form of poison-gas attack."

Similar commentary emanated from the Christian socialist The World Tomorrow, the conservative Saturday Evening Post, and the liberal New Republic. This media backlash led to a near-universal fear of propaganda and, coupled with the overt abuses of the Sedition Act and the horrors of World War I, contributed to a national mood of non-interventionism in European affairs.

This broad revulsion towards state-media collusion would not outlive the next world war, however. WWII came with its own propaganda campaigns and other illicit efforts to manipulate public opinion by the U.S. and British governments. While the FDR administration recognized that it could not use as heavy a hand as Wilson, it knew that marshaling Americans behind the war effort would demand a degree of media manipulation and narrative management.

Rather than use overt messaging from an organization like the CPI, which George Creel counseled FDR to rebuild, the White House relied on covert action by the FBI, surrogates in the friendly press, and British intelligence to generate the messaging that it desired.

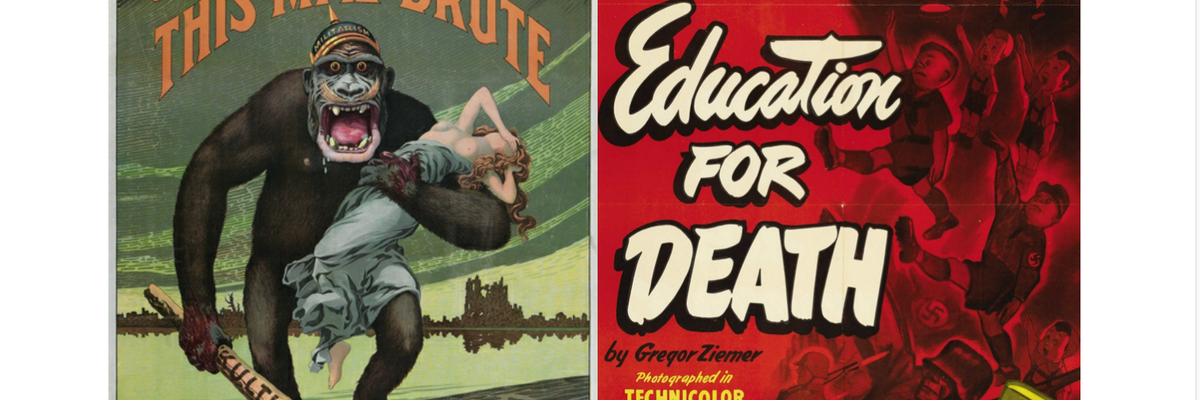

At FDR’s instruction and in tandem with British intelligence, J. Edgar Hoover's FBI illegally wiretapped and surveilled non-interventionists, particularly the America First Committee, and inserted Allied-friendly press coverage throughout the American media. British agents leaked negative stories to friendly media, financed Hollywood films critical of non-interventionism, and supported interventionist groups like the "Friends of Democracy" and the "Century Group," a network of wealthy and well-connected elites.

The BSC also inserted into American public discourse outright falsehoods. In one such episode, the BSC leaked a fake map to the White House, reportedly showing Nazi occupation and partition plans for Latin America. FDR, in turn, referred to the map during an address on 27 October 1941 as evidence to support his continued drive towards military preparedness. This episode, and other embellishments, created a climate of fear, later called the Brown Scare, which exaggerated the domestic threat of fascism and eroded civil liberties.

As with the Great War, revelations about media manipulation during the Second World War would eventually be exposed. As with the previous war, British intelligence officers told of their exploits in a series of memoirs published in the early 1960s. However, unlike the interwar period, these revelations did not cause the same public outrage outside of some conservative circles. Unlike the Great War, the triumph of the Second World War, coupled with the horrors of the Nazi regime, made such duplicities seem minor.

Later on, the FDR administration's media manipulation and the U.S. government's sordid Cold War record came to light during the deliberations of the Senate’s Church Committee and the House of Representatives’ Pike Committee. The committees were formed in response to early revelations of intelligence community misconduct that emerged from the investigative reporting by New York Times journalist Seymour Hersh who, in 1974, reported that the CIA had spied on domestic antiwar activists for at least a decade. Both committees uncovered a systematic chain of intelligence community abuses dating back to WWII, including efforts to manipulate domestic media, surveil and sabotage the anti-war and civil rights movements, and illegally surveil the international communications of American citizens.

However, these revelations failed to rouse the American public’s outrage. While the committees' work resulted in reforms that enhanced the legal framework for Congressional oversight of the intelligence community, its revelations of wrongdoing proved to have only a relatively short-lived impact on public opinion and the nature of mainstream media coverage. As historian Kathryn S. Olmsted has argued, despite the revelations of Watergate and the horrors of Vietnam, the American press still bought into the Cold War consensus that deferred to a robust foreign policy for countering communism and pursuing global primacy. As such, corporate journalism did not want to challenge the security state and risk undermining the U.S. government's larger foreign policy project. Similarly, Church's committee did not want to dive too deeply into the government's misconduct lest they permanently damage the credibility of the U.S. government.

This history does not bode well for oversight as the federal government has developed new practices for manipulating mass media, and the corporate press appears happy to oblige. In recent years, the major cable news networks have staffed their foreign policy and national security punditry positions with former intelligence and military officials. While not unlawful, the encroachment of said "experts" makes it difficult for these networks to fulfill their supposed role as a watchdog over government power. This is particularly so when these talking heads’ personal conflicts of interest are left undisclosed.

Similarly, early Twitter files revelations suggest that Silicon valley is cooperating, often willingly, to boost U.S. government information operations on social media. Lastly, these practices have joined a longstanding tradition of federal officials' use of selective leaks, journalists' deference to their government sources, and Defense Department’s collaboration with Hollywood, to create a new iteration of the information state.

If future efforts to rein in the information state are to succeed, such endeavors will require genuine bipartisan support and a commitment to this country's liberal democratic ethos that predates party politics. Individual consumers of news and media must also educate themselves about these practices if they wish to make informed political choices on America's role in the world. America can only survive as a republic if its citizens can make informed and unfettered political choices concerning the most fundamental political question of all – war and peace.