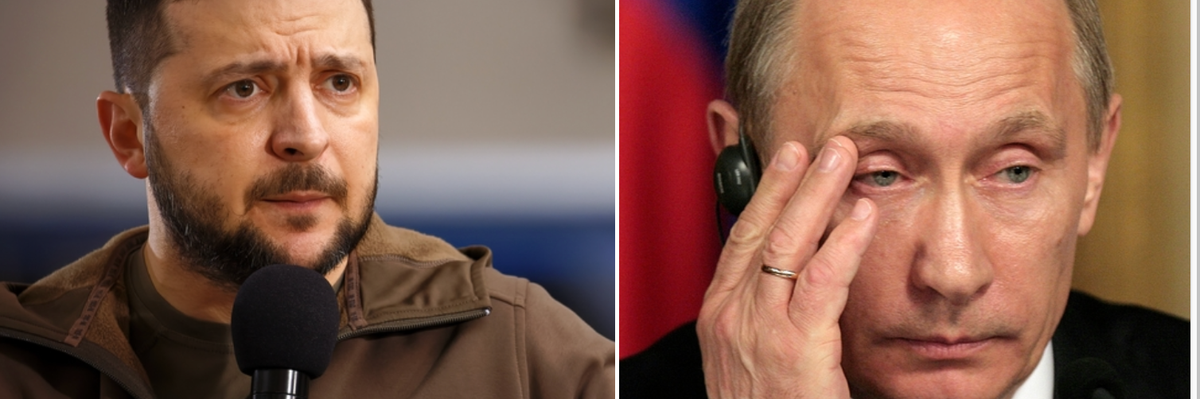

The animosity between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has been bitter. Agreement on anything — which would be a starting point for talks — is elusive. For the first time in several months, however, the two leaders have agreed on something. Unfortunately it takes them even farther away from talks than they are today.

They both seem to believe that the Minsk II agreement, a 2015 deal that many believed would be a way forward to peace in the region, is dead.

At some point this horrifying war will end. And it will have to end with talks. Those talks will have to, at some point, settle the issue of the eastern lands caught in a decades-long tug of war. Zelensky has said that a precondition for talks is "restoration of [Ukraine’s] territorial integrity,” meaning the Donbas, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, and even Crimea. Russia has said that negotiations can only be held on the basis of existing geopolitical realities and maintains that any negotiated settlement must respect Russia’s annexation of these same regions. That is the principal roadblock to a settlement. A big one.

That roadblock has been solidified and reinforced, not dissipated or lessened, by a recent agreement in statements made by the two leaders.

On November 15, addressing the G20 summit in Bali by video link, Zelensky rejected any return to the Minsk agreement. "We will not allow Russia to wait, build up its forces, and then start a new series of terror and global destabilisation. There will be no Minsk 3, which Russia will violate immediately after the agreement,” he insisted.

The Minsk agreements of 2014 and 2015 provided the best diplomatic solution to the crisis. Brokered by France and Germany, agreed to by Ukraine and Russia, and accepted by the U.S. and UN, the agreement was meant to peacefully return the Donbas to Ukraine while granting it full autonomy. Minsk II promised autonomy to the Donbas within Ukraine. The prospect of neutrality and the issue of NATO membership were expected to come later.

Former US Ambassador to the Soviet Union Jack Matlock recently said that "The war might have been prevented – probably would have been prevented – if Ukraine had been willing to abide by the Minsk agreement, recognize the Donbas as an autonomous entity within Ukraine, avoid NATO military advisors, and pledge not to enter NATO."

But Zelensky’s words in Bali, though diplomatically well chosen for his audience, did not accurately reflect history. It was not Russia who used the time provided by the agreement to build up its forces before violating the agreement. It was Ukraine.

In 2019, Zelensky was elected in large part because his platform of making peace with Russia and signing the Minsk II Agreement won him the Russian-speaking vote in the south and east. But to fulfill his promise, Zelensky had to have the support of the U.S. He didn’t get it. Abandoned and under pressure, Zelensky refused to implement the agreement. The U.S. then failed to pressure him back onto the road of diplomacy.

Richard Sakwa, Professor of Russian and European Politics at the University of Kent, told RS that "as for Minsk, neither the U.S. nor the EU put serious pressure on Kiev to fulfil its part of the agreement." Anatol Lieven, Director of the Eurasia Program at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, agrees. Though the U.S. officially endorsed Minsk, Lieven told RS that "they did nothing to push Ukraine into actually implementing it."

Zelensky was not the first Ukrainian president to fail in implementing Minsk. In fact, Ukrainian President Pyotr Poroshenko may have negotiated it with no intention of ever implementing it. In May 2022, Poroshenko told the Financial Times that Ukraine “didn’t have an armed forces at all” and that the “great diplomatic achievement” of the Minsk agreement was that “we kept Russia away from our borders — not from our borders, but away from a full-sized war.” In other words, the agreement bought Ukraine time to build its army.

Poroshenko told the Ukrainian media and other news outlets that “We had achieved everything we wanted. Our goal was to, first, stop the threat, or at least to delay the war — to secure eight years to restore economic growth and create powerful armed forces.”

Some have countered that Russia shares blame for the failure of the agreement because they have shirked responsibility by claiming to be a facilitator of the agreement rather than a party to a deal that is fundamentally between Ukraine and the separatist Luhansk and Donetsk Peoples’ Republics. Notably, Russia would also have had to withdraw all of its military from the Donbas if Ukraine had passed a law guaranteeing autonomy to the region. Given that Ukraine never passed such a law, we will never know if Russia would have made good on its promise.

Whoever killed the Minsk agreement, Putin agrees with Zelensky that it is dead. Ten days after Zelensky said it could not be revived, Putin said that agreeing to the Minsk agreement had been a mistake he would not repeat, suggesting there would be no Minsk III.

Dmitry Trenin, professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, points out that when Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, Putin was acting “on a mandate from the Russian parliament to use military force ‘in Ukraine’ not just in Crimea.” But Putin stopped short of annexing the Donbas and agreed, instead, to autonomy for the Donbas within Ukraine under the Minsk agreement.

Putin has been harshly criticized by hardliners in Russia for not going further than the annexation of Crimea by annexing the Donbas as well. Lieven told RS that the hardliners criticize Putin for trusting Germany and France’s promise to ensure the implementation of the Minsk Agreement instead.

In his recent statement, Putin said he had been wrong. “Today it has become obvious that this reunification [of the Donbas with Russia] should have taken place earlier.”

But in 2014, Putin said, he “believed that we would manage to come to terms, and Lugansk and Donetsk would be able to reunify with Ukraine somehow under the agreements – the Minsk agreements.”

That Putin’s hopes that Minsk II would succeed proved false in no way justifies his subsequent decision to carry out a brutal invasion of Ukraine.

But Putin and Zelensky seem to have come to the same place for very different reasons. Zelensky does not trust that Putin won’t take advantage of the lull provided by a Minsk III agreement to build up his forces before violating it and terrorizing Ukraine with renewed force; Putin doesn’t trust that Zelensky will negotiate a settlement on the eastern territories that will calm the complicated strife. They both, nearly simultaneously, announced that the most promising hope for a diplomatic solution to the crisis is dead.

So, in the end, the only thing the two leaders agree on is this: it is not at all clear what the road to a negotiated settlement would look like.