Amid President Biden’s controversial decision last week to soon meet with Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman — a move that appears to be following the lead of prominent Middle East hawks — the Government Accountability Office released a new report finding that the State and Defense Departments failed to thoroughly investigate and “don’t know” whether the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen used American-made weapons in attacks that killed civilians.

What’s perhaps more revealing about the GAO’s assessment is that it shows the militaristic mindset and poor judgment that got the United States into this strategic and humanitarian nightmare in the first place are alive and well inside the executive branch.

First, the background: For years, Congress has attempted to get straight answers from the executive branch about how involved the U.S. national security state has been in Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s military intervention in Yemen that began in March 2015. Eventually, through compromises — like H.Res.599 that put Congress on record acknowledging U.S. military involvement in the war in Yemen for the first time, and activism-driven wins, like building bipartisan majorities to lead unprecedented votes against U.S. military involvement — oversight has revealed the complicated web of ways the U.S. military was or remains engaged in the Gulf monarchies’ war.

Indeed, this new GAO report resulted from Rep. Ro Khanna’s amendment to the Fiscal Year 2021 National Defense Authorization Act. The GAO — an independent government auditing agency — reviewed what forms of material support, and their impact, the State and Defense Departments provided to the Saudi-led coalition through the end of 2021. It also reviewed the agencies’ compliance with existing U.S. law, including another previously passed Khanna NDAA amendment requiring the Pentagon to review credible allegations of U.S. military or intelligence personnel involvement in the disappearance and torture of Yemenis by Emirati, Emirati-affiliated, and Yemeni security forces in the south.

Among other issues, the GAO found that both the State Department and the Pentagon could not say whether U.S.-made armaments have been used in Yemen without authorization or in violation of international law. It also found that these agencies did not effectively track Saudi, Emirati, or their proxies' use of U.S.-provided military assistance, and it could not provide any evidence that it had meaningfully investigated allegations of apparent war crimes using U.S.- provided weapons.

In short, nothing has changed. Back in 2018, after prodding by Senator Elizabeth Warren, then-CENTCOM commander General Joseph Votel (who is now retired and head of a Pentagon contractor industry association) revealed that the U.S. military was not tracking where non-U.S. jets were going after refueling in midair on the U.S. taxpayer’s dime. Yet, four years later, the GAO’s confirmation that the U.S. government is still failing to effectively monitor and track how U.S. military support to Saudi Arabia and the UAE is being used in Yemen is important, but still doesn’t explain why.

The answer is not that the Pentagon doesn’t have the capacity or the resources to be tracking this assistance or performing more effective end-use monitoring. It’s because the underlying goal of these programs that transfer military assistance is, as some experts have observed, to offer “the putative promise of bolstering deterrence in great power competition, improving access to and influence over foreign partners, and enhancing the effectiveness of partner militaries.” In other words, they’re meant to be a tool to maintain global U.S. military dominance, not reduce civilian harm.

The apparent willful ignorance of the U.S. government also reflects how it interprets its obligations under customary international law (or rather exempts itself). If a weapons-exporting country has reasonable suspicion to think selling more weapons may result in violations of international law, based on previous instances of harm, and nonetheless continues to sell weapons, the seller is legally liable for crimes committed. U.S. government lawyers beg to differ, arguing that this liability applies only when such misuse can be shown to be intentional — evidence which is hard to provide, let alone available unless the U.S. government was tracking how its military support was being used in the first place.

The report also reveals much about these agencies’ internal culture, which appears to incentivize continuing to materially arm the Gulf monarchies at war in Yemen and elsewhere, except in rare exceptions — even if it requires downplaying years of internal legal concerns. U.S. officials regularly say they don’t know or don’t have enough information to answer official questions about whether U.S. military assistance was implicated in civilian harm events. Apparently the U.N.’s investigations and documentation of hundreds of violations of international law in Yemen since 2018 — many involving U.S. armaments or supported actors — are insufficient evidence to determine whether providing more weapons will do more harm.

And yet, despite acknowledging its awareness of ongoing reports and such mounting evidence of war crimes, according to the GAO, these agencies still “have not investigated these cases to determine if or how U.S.-origin equipment was used for unauthorized purposes, such as in violation of the agreements under which the defense articles were provided.”

Congressional follow-up is important, but the bigger lesson here is that any U.S. talking point that has claimed that arming or providing military support to the Saudi and Emirati governments is effective at reducing civilian harm in Yemen is now demonstrably false.

It’s also important to note that the GAO’s mandate is only to audit the agencies’ compliance with U.S. law and internal documentation, consistent with the original request from Congress for a review. It does not make an assessment of anything outside that scope. As such, the GAO did review whether the Pentagon fully answered a statutorily required report about U.S. or its partners’ involvement in torture in Yemen or whether it delivered the report on time in compliance with the law. It did not, however, parse the meaning of the Pentagon's legalese in some of its response to Congress.

For example, DOD told Congress that it has not “observed” evidence of abuses, which is different from saying it has “obtained” such evidence, thus requiring it to act accordingly. The Department is relying on the narrowest interpretation of Congress’s request: It appears to be indirectly saying that the only “credible” reports of abuses are those from the Department — not independent investigators at the United Nations, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and local Yemeni civil-society groups such as M’watana Organization for Human Rights — otherwise it does not have an obligation to investigate further.

Those are hard questions Congress must still transparently investigate while holding the Pentagon to account for its obfuscation. If Congress finds sufficient evidence that U.S. partner forces are credibly implicated in torture and other grave abuses on its own (they are), it should enforce the law through appropriations.

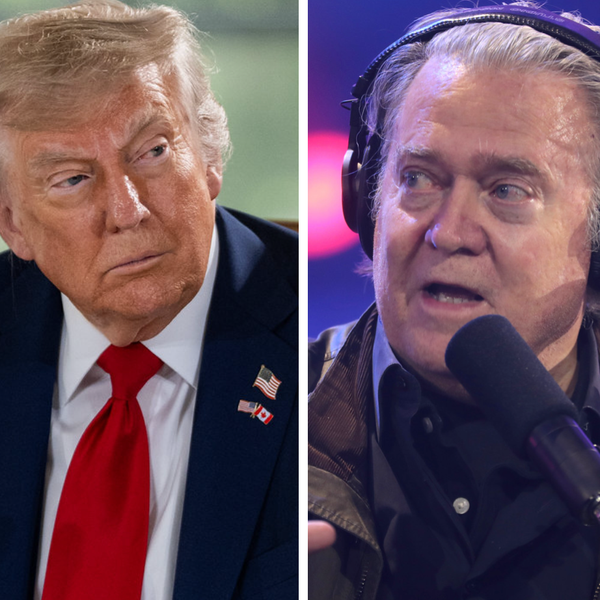

Curiously, the GAO fails to cover a critical aspect of U.S. military support for the Saudi-coalition’s intervention — the sale of munitions and other weapons through the direct commercial sales program, or DCS. While it mentions DCS in passing, the GAO’s review appears to have covered items sold only through the Foreign Military Sales program. The majority of U.S. weapons sold to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, especially during the Trump administration, was through the DCS program, which has less public oversight and only requires the State Department to approve an export license for a U.S. company to sell weapons.

Congress should follow up asking why DCS was left out of the GAO’s review.

Despite clear red flags of the harm it is doing, the United States has been aiding and abetting war crimes in Yemen and flouting its responsibilities as a weapons exporter under international law. Even U.S. policymakers who care only about Washington’s power projection should protest the fact that the Biden administration, like its three predecessors, continues to provide a model for human rights abusers everywhere on how to evade accountability for enabling war crimes, civilian harm, and famine.