Both the Trump and Biden administrations had an easy relationship with the deeply conservative government that has ruled Colombia since 2018.

U.S. officials, who call Iván Duque’s Colombia “a keystone of the region,” have been more content with the 45-year-old president’s performance than most Colombians, who give him a mere 20-percent approval rating. Duque’s four years come to an end in August, and Colombia will elect a new president on May 29, with a second, run-off round on June 19.

This will be one of the most consequential and contested elections ever for Latin America’s third-largest country. The result will have major implications for the U.S. government, which has given Colombia more than $13 billion in assistance so far this century, far more than for any other country in the hemisphere.

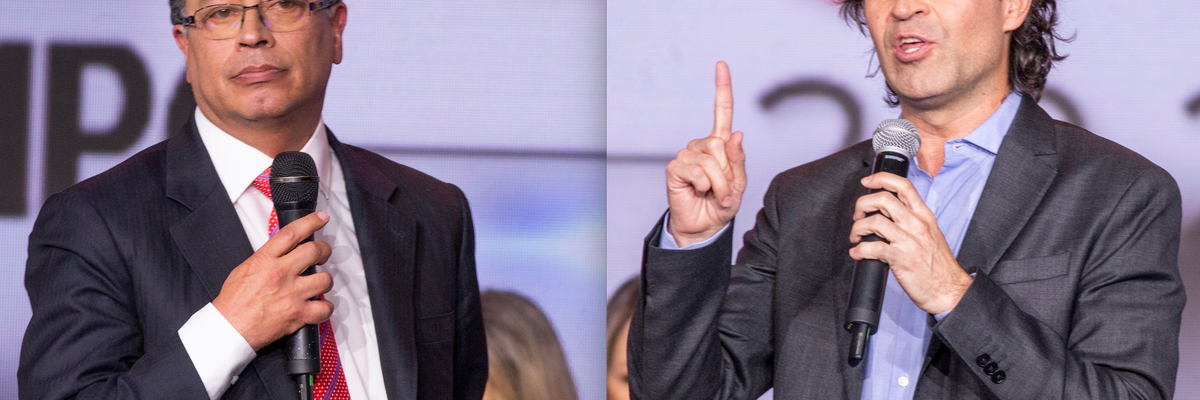

Head-to-head second-round scenario polling shows a razor-thin margin between the two leading candidates, who represent dramatically different visions of government. Federico “Fico” Gutiérrez, a former Medellín mayor, offers continuity with Duque’s conservative politics, which the Biden administration might find reassuring. It would, however, mean continuity with a model of which most Colombians appear to disapprove after four years of worsening violence and economic insecurity.

Gustavo Petro, a former leftist guerrilla and mayor of Bogotá, offers radical change that could consolidate a 2016 peace accord and implement reforms to address one of the world’s worst records of income and land inequality. Petro leads in first-round polling by a comfortable margin. However, he carries a strong whiff of populism and appears open to cooperation with China and Russia, which worries the United States. U.S. diplomats have sounded alarms about Russian interference in Colombia’s campaign, mostly via social media, and they could only be referring to Petro.

Also polling in low double digits is Rodolfo Hernández, a septuagenarian former governor running as an independent. Hernández is a right-of-center populist with unorthodox views (he told the U.S. ambassador that he favors legalizing drugs) and is campaigning mostly on social media. Roughly tied with him is Sergio Fajardo, a well-regarded but uncharismatic former mayor and governor who, as a moderate technocrat, probably offers a combination of peace accord implementation and pro-Western outlook that Washington would find comforting. At this moment, it’s unlikely that either Hernández or Fajardo will reach the second round, but both could offer powerful second-round endorsements.

Iván Duque’s political party was founded by former president Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010), a hard-right politician with a troubled human rights record, but who achieved security improvements. One of the most pro-Washington Latin American leaders in memory, Uribe received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush. Uribe and Duque’s “Democratic Center” party has populist-militarist tendencies and represents large landowners and big business in one of the world’s most unequal countries. Still, U.S. officials of both parties have been comfortable working with leaders from the CD and its coalition partners since they share so much of Washington’s agenda — from openness to investment and 1980s-style hardline anti-drug policy, to animosity toward Venezuela, condemnation of Russia, and skepticism about China’s regional intentions.

Duque bested Petro in the second round of the 2018 election, but good relations with Washington have not been enough to save his presidency. He took power after a peace accord demobilized the country’s largest guerrilla group, but failed to take the country’s security policy off of its war footing. While the military reacted to provocations without a clear strategy, vast areas of the country were left ungoverned; new armed groups rushed to fill the vacuum left by demobilized FARC guerrillas, and coca cultivation increased.

As commodity prices slid and COVID slammed the economy, Duque ran out of resources. His government was reluctant to increase taxes on the wealthiest, choosing instead to impose a regressive tax hike that resulted in last year’s mass protests, which in turn were prolonged by a brutal response from a police force shaped by decades of armed conflict. Meanwhile, implementation of the 2016 peace accord has fallen ever farther behind, and Colombia is now considered the world’s most dangerous country for social leaders or environmental defenders. Today, Duque and Uribe are both unpopular and have few “coattails” to offer Gutiérrez, their preferred successor.

This gives an advantage to Gustavo Petro, whose coalition won the most seats (though far short of a majority) in last month’s legislative elections. To some extent, the campaign is a referendum on Petro, probably the most progressive of any viable presidential candidate since 1945. Colombia has been a dangerous place to be a leftist politician since at least the 1940s. That a former guerrilla with progressive views can be a frontrunner points to a major opening, enabled by a peace accord that broke the link in citizens’ minds between “progressive politics” and “destructive guerrillas.”

Petro promises to fully implement the peace accord, increase the government’s presence in the countryside — probably the best long-term drug supply-reduction strategy — and reform drug policy. He made his name 15 years ago as an anti-corruption senator.

He is not a perfect candidate, however. With a reputation for craving attention and preferring conflict over compromise, he worries institutionalists by proposing to rule by decree on economic issues. He has been notably quiet on the Ukraine invasion, failing to explicitly condemn it. And while he proposes a “social pardon” for some criminals, his brother just visited a Bogotá prison to meet with politicians jailed for corruption, triggering a scandal that mars his anti-corruption brand.

Regardless of who wins, the vote result is likely to be valid: despite unusual hiccups during March legislative balloting, Colombia publishes results more quickly, and more transparently, than the United States. (Vote-buying, however, is common, especially in poor areas.) The result will most likely reflect the will of the Colombian people, and Washington will have to respect it, as its diplomats have pledged to do.

If Petro wins, U.S. officials shouldn’t expect him to jet off immediately to Caracas and Moscow. There will be a honeymoon period that skilled U.S. diplomats must seize as an opportunity to build a working relationship by supporting policies to bolster the peace accord and reduce poverty, and to encourage Petro’s less-populist tendencies. (It doesn’t help that Washington is unlikely to have a confirmed ambassador in Bogotá by August.) To reject him from the outset would likely push him toward great-power rivals.

If Fico Gutiérrez wins, the Biden administration’s approach should start with the need to rescue the peace accord, especially its rural governance provisions, from the Duque government’s bare-boned implementation and neglect. Though it would mean pushing against some long-entrenched preferences in Washington’s law enforcement and drug-war bureaucracies: a new approach to drugs and organized crime, based on enhancing state presence in ungoverned areas and fighting the official corruption that fosters organized crime is desperately needed. Punishing corruption may be a much more difficult challenge in a Gutiérrez government, which will include many of the longtime regional political bosses and landowners who have fostered it.

If the election is close, U.S. messaging will be even more important. If a candidate wins with 51 percent in today’s polarized climate, the danger that the loser will reject the result is real. The left would mobilize in the streets. The military may rattle sabers. Absent concrete evidence of fraud, U.S. officials must work multilaterally and avoid any public pronouncements — even unintended gaffes — that cast doubt on the result. The top U.S. interest will be in helping Colombia and its democracy get through what could be its most serious challenge in 70 years.