Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, many analysts claim that China is taking a “pro-Russia” stance. Beijing’s refusal to condemn Moscow’s invasion — or call it an invasion — and the Chinese media’s imitation of Russian propaganda are seen as evidence of China’s lean to one side.

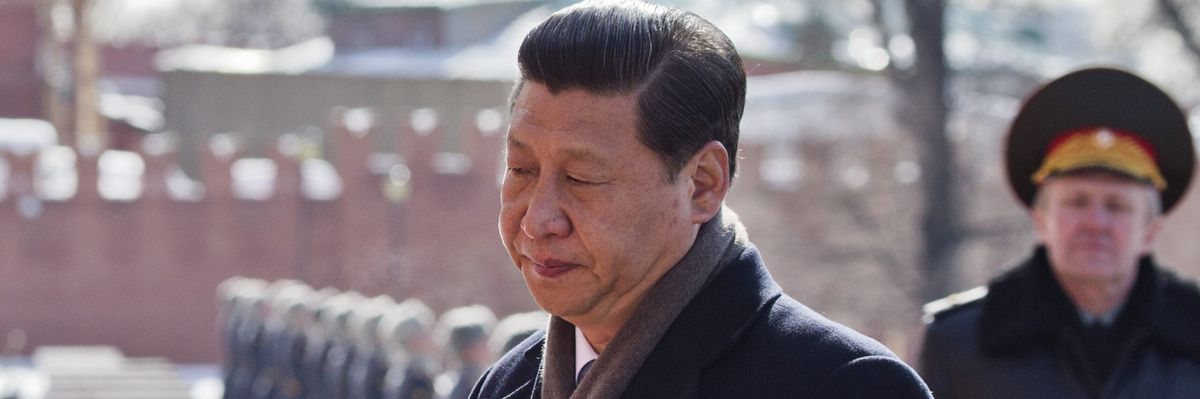

China’s diplomatic support for Russia is to be expected, given President Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin’s “no limits” partnership agreed to three weeks prior to the Kremlin’s offensive. But what is surprising about China’s stance is how little material support Beijing has provided to its “most important strategic partner.” Even President Biden’s national security adviser Jake Sullivan has said he has not seen evidence of China providing military support to Russia.

While it is difficult to glean the intentions of Chinese decisionmakers, China’s actions speak louder than words. Xi Jinping undoubtedly believes that Putin is an important strategic partner at a time when China is facing mounting pressure from the United States. On the other hand, Chinese officials likely recognize that supporting Putin's war effort would not only do little to advance China’s interests, but it would also subject China to potentially high economic and reputational costs. In this context, Beijing is walking a fine line by providing diplomatic support to Russia but stopping short of furnishing Moscow with arms and aid.

To arm or not to arm?

Over one month into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there appears to be limits to the “no limits” partnership between China and Russia. Diplomatically, Beijing has gone to great lengths to echo Putin’s justifications of the war, namely, by describing NATO enlargement as the “root cause of the crisis.” Even so, the Chinese government has not publicly backed Russia’s maximalist objectives, including ultimatums to “denazify” Ukraine, assert sovereignty over Crimea, and declare the independence of Donetsk and Luhansk.

On the economic front, Chinese officials claim they will maintain normal trade relations with Russia and not join international sanctions. But recent reports suggest that China’s largest state-owned banks stopped financing purchases of Russian commodities; Beijing refused to sell aircraft parts to Russian airlines; and Sinopec suspended major investments in the Russian gas market. Although these cases may be exceptions to the rule, the decision of some Chinese businesses to suspend transactions with Russia is notable in light of Chinese officials’ rhetoric to the contrary.

Finally, on the military front, there is little evidence that Beijing is backing Moscow. Although U.S. intelligence leaks suggest that China may have signalled willingness to provide Russia with surface-to-air missiles, drones, and other weapons, Sullivan again said he has not seen evidence of China acting on Russian requests for military support. Were proof of Chinese military aid to emerge, it would constitute a major shift in China’s position on the war.

China’s strategic calculus

Beijing’s mixed support to date is understandable considering the potential risks and limited upside to fully backing Russia. China undoubtedly wants to ensure that Russia remains a strong strategic partner to deter the United States. Nevertheless, after only one month of fighting, Russia’s logistical and intelligence failures cast doubt on even Beijing’s ability to make up for the damage done to Russia’s economy and military. Chinese leaders likely recognize that there is little they can do to meaningfully help Moscow reclaim its pre-war position, let alone win the war in Ukraine. In this context, any aid that China provides to Russia is likely to be more symbolic than substantive.

At the same time, there are several reasons that China would want to avoid provisioning large-scale arms and aid to Russia. First, for all of Beijing’s gripes with NATO and the United States, Ukraine is not China’s enemy. Before the war, China and Ukraine maintained cooperative economic, technological, and even military ties. While the Chinese government may dislike the current Ukrainian government, it is not in China’s interest to export weapons to be used against Ukrainian civilians.

Second, China remains a middle-income country whose major policy goal over the next decade is to catch up to the economic and technological development of the West — to legitimize its governance model, maintain social stability, and accelerate reunification with Taiwan. The war in Ukraine, however, has increased the price of commodities to the point that even discounted purchases from Russia are unlikely to offset the higher costs of inputs on which China’s economy depends. Moreover, the potential for Beijing to face secondary sanctions due to economic cooperation with Russia would only add to China’s economic headwinds, including latent COVID-19 outbreaks, capital flight, and declining population growth.

Finally, the longer the war in Ukraine drags on, the more unified Europe and the United States are likely to become, solidifying the very same alliances that China and Russia have been adamant to disrupt. The loss of Europe as a “wedge” between China and the United States would be a major strategic liability to Beijing.

Thus, it would make sense for Beijing to shy away from exploiting Russia’s offensive as a proxy war against Europe and the United States. Although Xi Jinping has identified the United States as the “biggest threat to China’s development and security,” this threat is exacerbated, not minimized, by the prospect of a prolonged war in Ukraine. Among the many important lessons of the crisis, one is that there remain limits to the China-Russia partnership.

- Xi’s whirlwind European tour, playing mediator to mixed reviews | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Ukraine and West are crossing red lines. Why isn't Russia reacting? | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Ukraine’s demographic crisis threatens its future viability as a free state | Responsible Statecraft ›

- New China port in Peru is about growth, but the sky is not falling | Responsible Statecraft ›