"Long hot summer" is the perfect descriptor for what awaits the Biden administration — and the American people — as troops and equipment roll out of Afghanistan for the promised withdrawal by September 11. The Taliban has taken over 40 districts and more territory everyday — including key provincial centers and yesterday, the country's main border crossing with Tajikistan.

Meanwhile, the Pentagon seems really restless and squirmy with the idea of fully leaving Afghanistan — despite all of its modulated talk to the contrary. In fact, a dip into one of its press conferences is much like peering through a kaleidoscope — it all sounds on the up-and-up, but in retrospect what you've got is a jumbled word salad that when re-assembled, doesn't read as positive as it endeavors to be. Like this, when DoD spokesman John Kirby was asked about the pace of the withdrawal (which the Pentagon apparently calls "retrograde") in light of recent Taliban attacks. From the DoD website Monday:

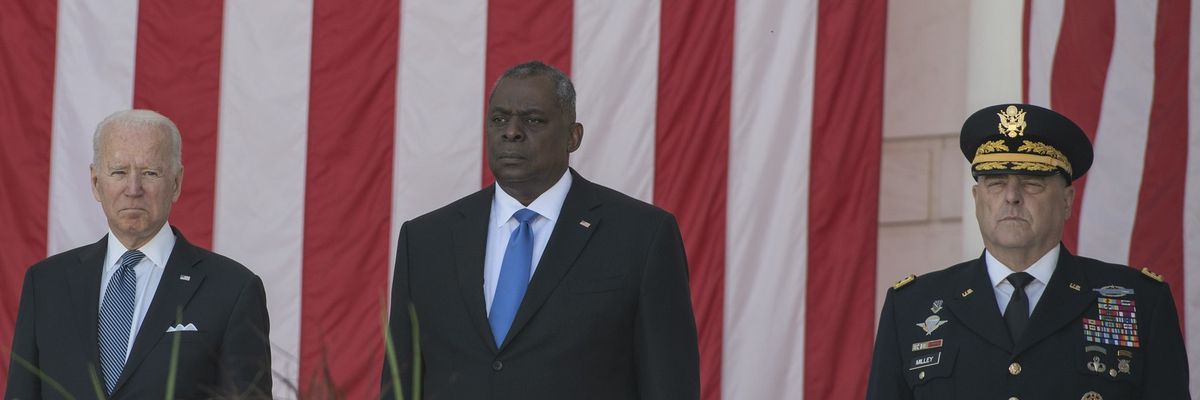

The Taliban have attacked Afghan government bases and units. Kirby said that Austin and military leaders in the Pentagon, at U.S. Central Command and in Afghanistan, "are constantly looking at the pace we're going at, and the capabilities we have, and the capabilities that we're going to need throughout to complete the withdrawal," Kirby said. "So as we said, from the very beginning; while there is a schedule, we are mindful that that schedule could fluctuate and change, as conditions change."

Kirby said there are only two aspects of the Afghanistan retrograde that will not change: The first is the U.S. military will withdraw all U.S. forces from the country, and the second is the withdrawal will be finished by the September deadline set by President Joe Biden.

The report goes on to say that in order to ensure those "capabilities," the USS Eisenhower aircraft carrier is going to extend its deployment to the region.

Commanders at many levels are wrestling with what over-the-horizon counterinsurgency and over-the-horizon logistics will look like. The U.S. military can already provide the over-the-horizon support that the Afghan government will need, Kirby said, those capabilities already exist. Leaders are looking for better ways to perform the missions.

Furthermore, one of those "better ways" is clearly outsourcing.

Planners continue to look at ways to provide contractual support to Afghan forces once the retrograde is completed. "There's a range of options that we're looking at for how to continue to provide contractual support … specifically the Afghan Air Forces," Kirby said. "We're very actively working our way through that right now. We're looking at a range of options."

This conversation, mind you, comes two weeks after the New York Times reported that there is an active "debate" going on in the Pentagon over whether or not the military should seek authorization to conduct airstrikes to protect the capital of Kabul or other key Afghan cities like Kandahar that are vulnerable to Taliban takeover. The airpower would likely take the form of armed drones. Officials who spoke with the paper said this naturally leads to the question of the support capacity in the region (basing, fuel), which leads of course to the question of what kind of counter-terrorism presence the U.S. will have and where after September 11. If the military is given the authorization to provide air support to Afghanistan say, if Kabul is about to fall, then it will need some sort of basing.

This is music to lawmakers ears, of course, particularly the ones who did not want to get out of Afghanistan in the first place. “Our policy should be to do everything possible, consistent with not having troops on the ground, to enable the legitimate Afghan government and security forces to hold on,” Representative Tom Malinowksi, Democrat of New Jersey and a former State Department official, told NYT.

Surely, GOP Sen. James Inhofe, ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, would agree, as he penned an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal just a week ago, calling for Biden to "leave a small force of about 1,000 troops in Afghanistan until at least the spring of 2022."

As things heat up and they already are — see here, here, and here — members of Congress and especially the White House are going to be increasingly worried about the optics of Americans leaving a smoldering landscape, with vulnerable, innocent Afghans behind. Who knows what Afghan President Ashraf Ghani is going to say to pressure Biden when he visits Washington at the end of this week.

Like him or not (not!), ex-president Hamid Karzai hit it on the head with his comments to the press last weekend:

“We will be better off without their military presence,” he said. “I think we should defend our own country and look after our own lives. … Their presence (has given us) what we have now… We don’t want to continue with this misery and indignity that we are facing. It is better for Afghanistan that they leave."

Committed to ending our part in this war, this is the message we must keep in mind. It is the only way Afghans can move ahead — as hard as that will be in the near future.