Jun 18, 2021

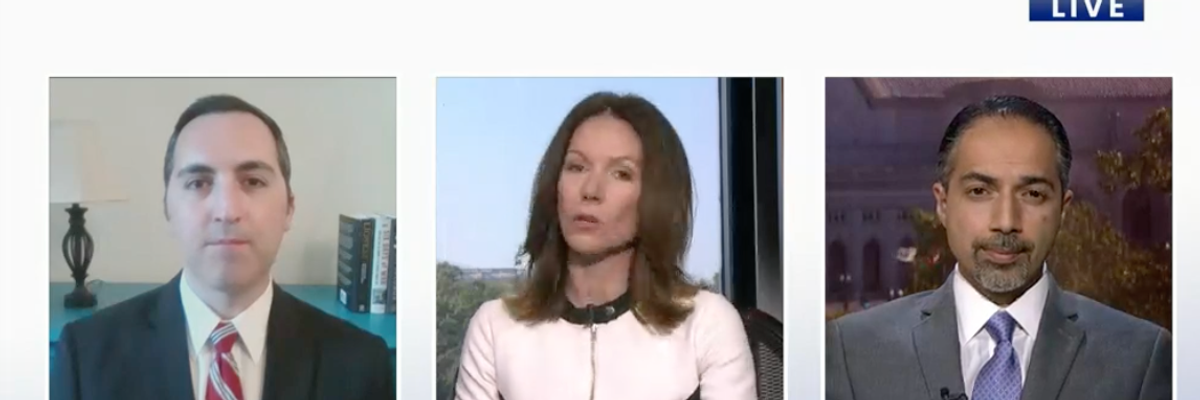

Quincy Institute's co-founder and executive vice president of programs Trita Parsi debated Richard Goldberg of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies today on CSPAN's Washington Journal program.

The two sparred a bit over today's presidential elections in Iran, the nuclear deal and U.S. sanctions on Tehran. They also took call-in questions. Watch below: