Iran’s top diplomat has completed a tour of the South Caucasus, where he met with all three heads of state but did little to resolve uncertainty about where Tehran fits in the emerging regional order.

Foreign Minister Javad Zarif’s whistle stop tour, which began on January 25, has included visits to Baku, Yerevan, and Tbilisi, as well as Moscow and Ankara. It was the highest-level visit by an Iranian official to the region since last year’s 44-day war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which ended in an Azerbaijani victory and a dramatically shifted geopolitical arrangement, with Russia and Turkey exerting newfound influence and everyone else – including Iran – trying to figure out where they now fit in.

At his first stop, in Baku, Zarif said his trip was inspired by the “3+3” formulation that has been mooted as a new post-war regional integration platform – the three Caucasus countries plus Russia, Turkey, and Iran. “I am taking up your suggestion of ‘3+3’ and I will be visiting all the six countries, five plus Iran,” he told President Ilham Aliyev. (While Zarif credited Aliyev with the suggestion, Baku in fact picked it up from President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey, Iran’s regional rival.) “We hope that this will be the beginning for peaceful, normal relations between the countries in the region.”

Zarif made perhaps the biggest splash of the trip in Baku when he congratulated Azerbaijan on its victory. “We are glad that Azerbaijan returned its territories,” he said. “Now that we have normal situation following territorial integrity restored and the occupation ended, Azerbaijani people can go back to the places of origin and Iran wants to help in doing that,” he added.

That was interpreted both in Baku and in Yerevan as indicative of a shift on the part of Tehran, which has traditionally tried to maintain a neutral position between its two northern neighbors.

“The ‘shift’ in Tehran’s rhetoric is visible with the naked eye. Until recently Iran had refrained from such strong or ‘one-sided’ formulations like ‘occupation,’ ‘liberation or your territories,’ or ‘restoration of territorial integrity’,” wrote one commentator in the Azerbaijani news website minval.az. The reason, she argued, was that Azerbaijan’s decisive military victory has forced Tehran to accommodate to Baku: “Now Zarif is hoping for new relations with Azerbaijan taking into account this ‘reset.’ Azerbaijan’s victory continues to determine the realities of regional politics.”

Zarif’s comments in Baku followed a largely hands-off Iranian approach during the war itself, as it tried to balance considerations including appeasing Iran’s large ethnic Azerbaijani population and Tehran’s distrust of rising Turkish influence in the Caucasus. There was one attempt, near the end of the war, by Iran’s foreign ministry to propose its own peace deal, but the effort was dead on arrival.

To Armenians, the proposal suggested that Iran had already begun to tilt toward Azerbaijan.

“Iran used to demonstrate a pro-Armenian approach,” said political analyst Garik Keryan in an interview with the Armenian news website 1in.am. “But in the last Karabakh war, Iran took a passive position […] which was reflected in the fact that Iran said it was coming up with its own resolution of the conflict, and then it turned out that it was simply to hand over all of the territories that de jure belonged to Azerbaijan.” Keryan added that Iran considered the outcome of the war – in which Azerbaijan regained control over most of those territories – to be positive and that “this explains why the foreign minister congratulated Azerbaijan on its victory.”

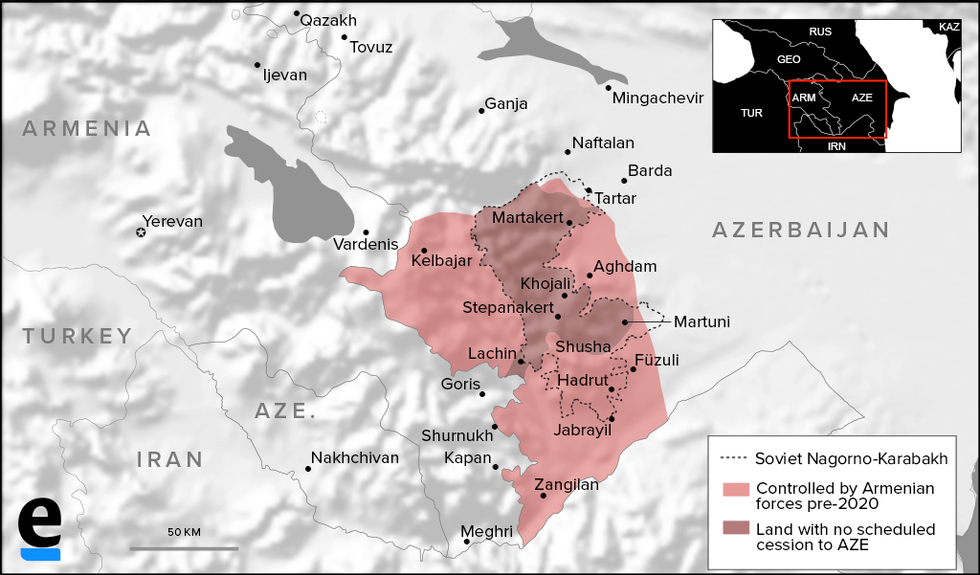

The content of the Iranian proposal hasn’t been made public, but Tehran had in the past tended to distinguish between Nagorno-Karabakh, an area that before the first war in the 1990s had a majority Armenian population, and the surrounding territories that Armenians also captured in that war, which were almost entirely populated by ethnic Azerbaijanis.

Zarif made one telling remark in Yerevan about Iran’s vision of territorial division in the Caucasus, when he told his Armenian counterpart Ara Ayvazyan that “our red line is the territorial integrity of the Republic of Armenia, on which we’ve clearly expressed our voice.” On the one hand, that could be interpreted as a reassurance to Armenians who fear Azerbaijani encroachment on the territory of Armenia in the light of irredentist statements from Azerbaijan and some confusion over territories on the Armenia-Azerbaijan border. But it also seemed to suggest that the territory that Armenians still control in Nagorno-Karabakh, including the regional capital Stepanakert, remains under question.

Despite Zarif’s friendly words in Baku, the fundamental concerns that Iran’s government has with Azerbaijan remain in force, said Eldar Mamedov, an Iran analyst and political adviser to the Progressive Alliance of Socialists & Democrats in the European Parliament. “It’s true that it goes farther than the usual Iranian rhetoric, and that it caused irritation in Armenia. But I think it’s more hedging than a real change,” he told Eurasianet.

Similarly, the public talk about regional integration did not reflect Tehran’s real interests. “Azeris have a tendency to overemphasize all these transport communications. For Iran, however, the issues related to its territorial integrity, the Azeri minority in Iran and Israeli influence are the most important. And that will not change,” Mamedov said. (He emphasized that his views are his own and do not represent those of his employer.)

Curiously, while he was in Yerevan Zarif mentioned Iran’s Armenian minority – "We also host a large number of Armenian compatriots and we have a long-standing relationship with them” – but in Baku did not bring up the far larger ethnic Azerbaijani population, perhaps indicative of the sensitivity of the latter.

Also in Yerevan, Zarif highlighted the issue of Syrian mercenaries that Turkey hired and transported to fight on Azerbaijan’s side. Tehran apparently fears that some of them may be Sunni extremists and is concerned about their presence so close to its borders. “Rejecting the presence of foreign terrorists and fighters in the region, Zarif described the presence of these forces as a common concern of the two countries,” the Iranian Mehr news agency wrote. If Zarif mentioned this in Baku, he kept it behind closed doors.

This article has been republished with permission from Eurasianet.