The Pentagon budget now stands at $740 billion, higher than at the peaks of the Vietnam War or Cold War. At the same time, we’re sure to see arguments that the trillions in emergency spending on the COVID-19 crisis require more austere federal budgets in the next administration.

For those who want to see a correction to bloated Pentagon spending — and the military overreach it represents — the deficit fears deeply ingrained in American politics may seem like a nifty political means. But this is at best a short-term strategy.

The events that arose from the last austerity movement, beginning with the 2011 passage of the Budget Control Act, can show us why.

As austerity politics took hold following the Obama administration’s $800 billion stimulus during the Great Recession, the BCA passed with bipartisan support in the new Tea Party Congress. The BCA aimed to bring back so-called fiscal discipline by placing strict spending limits over the next 10 years in the separate categories of military and nonmilitary spending.

The BCA did, in the very short term, result in a temporary reduction in Pentagon spending — a fact that was passionately decried by hawks and the Cold War-era old guard. Yet even with that short-lived downward trend, Pentagon spending was still higher than at the height of the Vietnam War or the Cold War. And the short-lived decline was followed by a robust increase, landing us at today’s $740 billion.

Instead of jumping on the austerity train for a shot at lower spending, the time has come for Pentagon budget watchers to dream a bit bigger.

The politics of austerity and the realities of the Budget Control Act have meant that for 10 years, it hasn’t been necessary — or possible — to have a real debate about Pentagon spending. In a fight over the national debt, it’s easy for those who are already inclined to defer to someone in a uniform on military policy to accept that the only problem with the size of the Pentagon budget is its contribution to the deficit.

This approach fails to build any opposition to military interventionism and the U.S. imperialist presence abroad, leaving a dangerous premise untouched: that the agency itself is essentially working as it should. Just like that, we’ve effectively ceded the discussion of what foreign policy (and therefore Pentagon spending) should be to the military maximalists.

What follows is something like what we saw in the 2010s: the Pentagon gets off the hook with a brief bit of belt-tightening and no real scrutiny, while the deficit soldiers move on to more politically palatable targets like the domestic safety net — and then Pentagon spending skyrockets once again.

For those who recognize the depth of the trouble we’re now in, austerity is already an enemy, since the obsession with the deficit is bad news for domestic investment as well. The resulting decay and dysfunction of American life may even fuel America-first politics and its reflexive militarism both at home and abroad — undermining Pentagon cuts by making the Pentagon into an even holier entity than it was already.

Then there’s the fact that the Budget Control Act has effectively cut off active opposition to Pentagon spending from left-leaning members of Congress.

For the last 10 years, a trail of bipartisan congressional legislation has repeatedly raised BCA spending limits — but this has meant that securing funds for domestic programs has been explicitly tied to accepting higher Pentagon spending, too. In 2019, many top progressives reluctantly supported a bipartisan budget deal that hiked the Pentagon budget for this very reason.

The Budget Control Act expires in 2021, and some on the right are calling for an extension.

This may present a tempting opportunity to halt the out of control growth in Pentagon spending,

but it hews too closely to the politics of the past. Our politics have shifted in nearly unimaginable ways since the Tea Party’s glory days. Imagine telling a 2011 version of yourself about the rise of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), the embrace of Black Lives Matter by a majority of Americans, the 2020 pandemic lockdown, or the simple fact of a Donald Trump presidency.

Powerful forces that didn’t yet exist in 2011, including the Movement for Black Lives, have called for Pentagon cuts. A July poll found that a majority of Americans would support cutting the Pentagon budget by 10 percent to fund domestic priorities — including half of Republicans. And polls have shown that voters of both major parties share a wish to see less U.S. military interventionism in the Middle East.

With all that in play, it’s no longer a given that sky-high Pentagon budgets — and the wars that drive them — are untouchable.

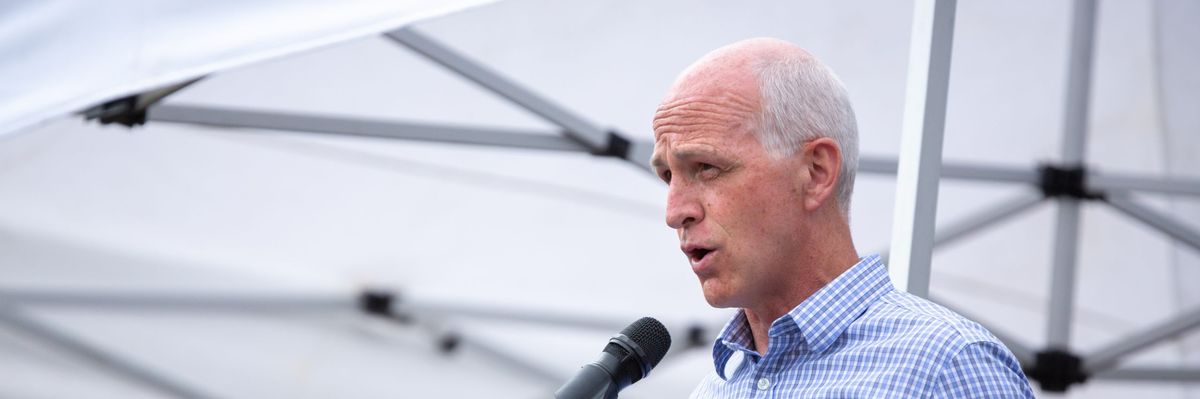

This summer, Sen. Sanders, Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.), and Rep. Mark Pocan (D-Wisc.) introduced matching amendments to the National Defense Authorization Act to cut Pentagon funding by 10 percent and invest instead in domestic needs. The measure wasn’t expected to pass, and didn’t. But it did win the support of 93 House members and 23 senators — a new watermark — and garnered the support of even mainstream lawmakers like Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer.

It signaled a revived fighting spirit to bring our military spending to heel — just in time for the expiration of the budget caps. In order to carry the fight forward, we must make sure austerity doesn’t once again stand in the way. The call to cut military spending should be paired with a demand for the investments that are worth making — and a critique of the wars that aren’t.

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org