So much wrongdoing to inspect, so little support from above in inspecting it. That seems to be the plight of inspectors general throughout the federal government during Donald Trump’s presidency. The most recent newsworthy plight is at the State Department, where Secretary Mike Pompeo has burned through two IGs during the past three months amid issues embarrassing to the himself.

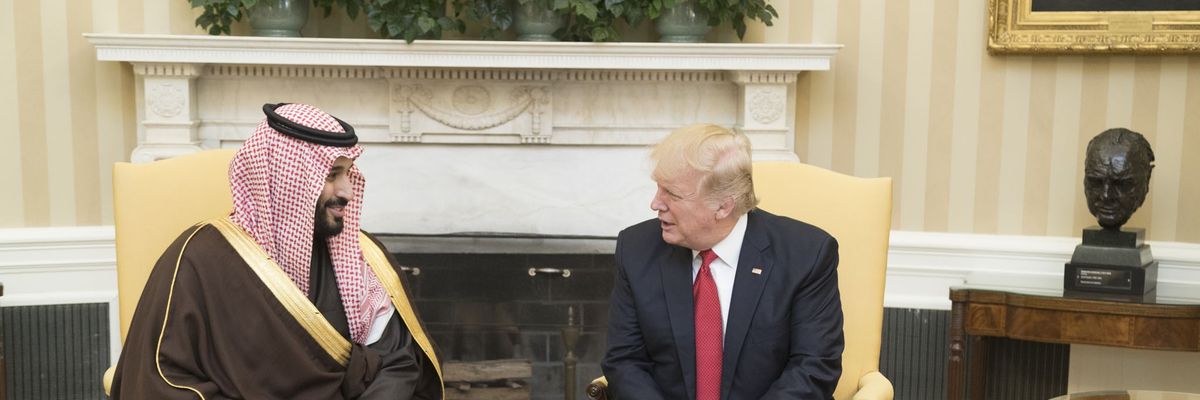

In May, Trump fired, at Pompeo’s behest, longtime State Department IG and career government attorney Steve Linick. One issue Linick’s office had been investigating at the time was alleged improper use of department employees to run personal errands for Pompeo. Another issue under investigation concerned whether Pompeo had acted improperly in circumventing congressional restrictions on arms sales to Saudi Arabia by declaring an “emergency” as the basis for approving such sales.

Pompeo has never offered a convincing explanation for sacking Linick, relying mainly on vague calumnies such as that Linick was a “bad actor.” An allegation that Linick’s office was leaking information about the investigations has not been corroborated, and Linick has denied it. Pompeo’s assertion that morale in the IG’s office was bad under Linick is not validated by employee surveys, especially when compared with morale in Pompeo’s own office.

The acting IG who was installed after Linick’s ouster, Stephen Akard, is a Mike Pence ally who, bizarrely, also continued to hold another State Department management position. Akard left a week ago after doing the IG’s job for only three months. Clearly Pompeo intends to hold anyone in that office on a very short leash.

This week the IG’s office finally did issue, under the auspices of the deputy inspector general, a report regarding the sale of arms to Saudi Arabia. But first, the press was treated to a session that immediately brought to mind Attorney General William Barr’s highly misleading pre-release spin of Robert Mueller’s report on Russian election interference. A “senior State Department official” gave not the slightest hint of anything critical in the report. Instead, the official proclaimed that the report found “no wrongdoing in the administration’s exercise of the emergency authorities that are available under the Arms Export Control Act.” Reporters repeatedly expressed frustration at the difficulty of formulating questions about a report they had not yet seen.

A frustrated Rep. Eliot Engel, D-N.Y., chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, later revealed that the anonymous “senior State Department official” was R. Clarke Cooper, assistant secretary for political-military affairs. Thus the person doing the pre-emptive spinning of the IG report was the head of the bureau whose operations had been inspected.

A redacted version of the report that the department later released, and even more so an unredacted version given to Congress and published by Politico, showed that the report was hardly the clean bill of health that Cooper portrayed in the spin session. The report concluded “that the Department did not fully assess risks and implement mitigation measures to reduce civilian casualties and legal concerns” associated with the transfer of precision-guided munitions to the Saudis and other Gulf Arab states.

The arena of conflict in question is Yemen, scene of a years-long Saudi-led aerial assault that has been the leading factor in turning that war into a humanitarian disaster. Outside estimates of the war’s toll include 100,000 dead and another four million people displaced during the past five years of fighting. The IG report itself cites a United Nations estimate that between March 2015 and November 2018 there were 17,640 combat-related civilian casualties, with 10,852 due to the Saudi-led air attacks.

The air war in Yemen has been by far the biggest Saudi military endeavor in the last few years, and it depends heavily on U.S. munitions and associated support. The Saudis use F-15 fighter jets and other U.S.-made equipment to deliver ordnance, and its air force would be grounded without continued U.S. logistic support.

As for the “emergency” procedure used to continue the flow of arms despite congressional opposition, the IG report took a very narrow view of this topic, noting only that the secretary went through the required procedural hoops and cited the relevant parts of statutes in making his declaration. The IG explicitly refrained from assessing whether a true emergency existed.

No such emergency does exist. One would exist if time were of the essence and an ally needed shoring up immediately — if, say, North Korea again invaded South Korea. Or to take an example from the Persian Gulf, when Saddam Hussein’s Iraq swallowed Kuwait in 1990 and threatened to continue its advance into Saudi Arabia, military assistance to the Saudis might have been legitimately considered an emergency.

Nothing remotely resembling that situation exists today. Iran, of course, keeps getting cited by the administration as the go-to threat whenever a threat needs to be cited. But Iran today isn’t on the verge of attacking or invading anybody, and hasn’t been for some time. The most aggressive actions Iran has taken regarding Saudi interests were taken almost a year ago, and even then only as a response to the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign and effort to destroy the Iranian oil trade.

The procedural timeline described in the IG report belies the notion that the arms transfer involved was a matter of urgency. The use of an emergency exception was first proposed inside the department on April 3. The emergency certification was drafted on April 23. The certification was transmitted to Congress on May 24. Some entire wars have been fought during that much time.

Another part of the background that should be considered in arms transfers to Saudi Arabia is the military balance in the Persian Gulf. Simply put, Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf Arab states are already far ahead of Iran both in military spending and in purchases of foreign-made arms. Most of what passes for an Iranian air force belongs in a museum. The shortfalls in Iranian military purchases are not due just to the nuclear-related arms embargo that the Trump administration wants to extend. Economic realities and competing priorities make it unlikely Iranian military purchases would increase significantly even without the embargo.

The administration’s conduct in this episode illustrates three patterns. First, U.S. arms sales to the Middle East and specifically the Persian Gulf region have been exacerbating, not reducing, insecurity and instability, as the tragedy of the Yemen war demonstrates. Second, the administration is abusing provisions such as emergency exemptions to defy the will of Congress, not to deal with true emergencies. Third, the administration is rejecting accountability for its actions and undermining mechanisms, including departmental inspectors general, designed to provide accountability.