Ever since Turkey’s military incursion into northeastern Syria in October 2019, dubbed “Operation Peace Spring,” and particularly after the Syrian government’s offensive on rebel stronghold Idlib in December with the crucial assistance of Iran-allied militias, bilateral ties between Ankara and Tehran have increasingly sourced. Until now.

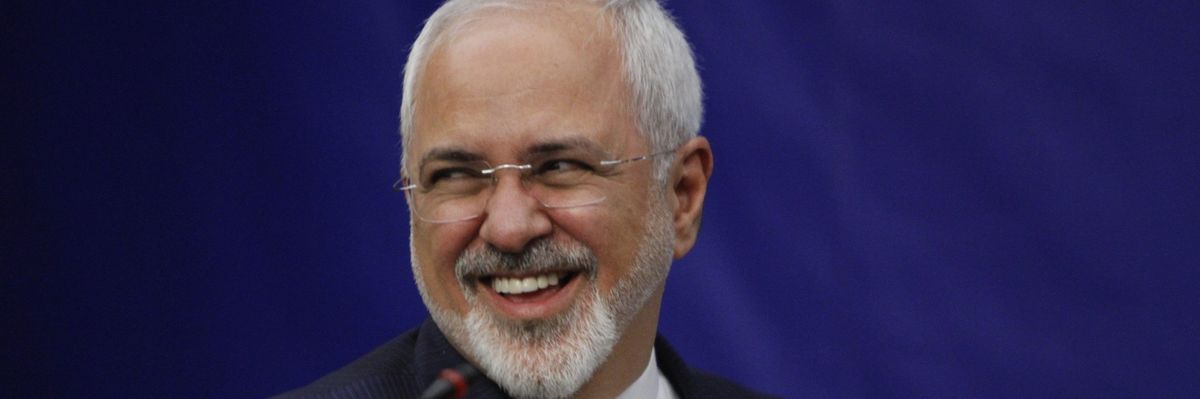

In a surprise announcement that marked a noticeable shift in Iran’s regional policy, Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif declared Tehran’s “support” for the Turkey-backed “legitimate” Government of National Accord in Libya during a joint press conference with his Turkish counterpart Mevlut Cavusoglu on June 15. It was the Iranian government’s first official endorsement of GNA amid claims and rumors that the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps is surreptitiously transferring arms to forces of the Russian-backed Libyan National Army led by Khalifa Haftar.

On the same day, Turkey launched an all-out military operation against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, positions in northern Iraq. In another surprise move and despite Tehran’s usual objections to any violation of Iraqi sovereignty, the IRGC simultaneously initiated its own assault from the east and struck positions of Kurdistan Free Life Party, a Kurdish militant group that seeks autonomy for Iran’s minority Kurds and is believed to be closely associated with PKK.

The abrupt convergence of geopolitical and security interests between Tehran and Ankara, or more precisely, Iran’s efforts to mend fences with Turkey, is no accident. Increasingly squeezed by the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign of economic sanctions and constantly pushed back by the U.S.-led constellation of its Arab rivals including in Iraq, Iran has been in dire need of a regional opening to alleviate the consequences of isolation, and Turkey in a good position to facilitate it despite longstanding mutual differences in Syria. Turkey’s potential as a U.S. ally and assertive regional actor is particularly significant for the leadership in Tehran because unlike during the Obama era, it has been reluctant to help Iran evade American sanctions under Trump, leaving Iran more vulnerable and forcing Iranians to rely increasingly on Iraq for the purpose. While the volume of Iranian-Turkish bilateral trade has plummeted about 50 percent due to reimposition of US sanctions — from around $10.7 billion in 2017 to almost $5.6 billion in 2019, according to one estimate — Iran’s economic relations with Iraq are booming despite increased U.S. pressure on Baghdad to reverse the trend.

But Libya and the Kurdish question are not the only policy areas where Tehran’s and Ankara’s interests may converge. In the June 15 joint press conference with his Turkish counterpart, Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif also made a significant, yet mostly neglected, mention of Yemen. “We have common views with the Turkish side on ways to end the crisis in Libya and Yemen,” he said, indicating the possible emergence of a regional realignment between Iran and Turkey against the Saudi-led bloc in the Yemeni and Syrian conflicts.

Since the start of the Saudi-led coalition’s invasion of Yemen in March 2015, Turkey supported the coalition's military campaign, opposing the Iran-backed Houthis. However, as Turkey's relations with Saudi Arabia soured in 2018 over the Khashoggi murder scandal, Ankara began reconsidering its position toward the conflict. Now that the Saudi-led campaign has failed to defeat the Houthis and at the same time, Riyadh has been experiencing growing disagreements with its ally, the UAE, over their long-term plans for Yemen, Turkey has adopted a more active policy toward the Yemeni civil war.

In the context of this new approach, Turkey seeks to increase its influence in Yemen, especially in the southern parts of the war-ravaged country, through actively supporting al-Islah Party, which is known as the Yemeni affiliate of the Muslim Brotherhood. Additionally, there have been reports recently of the Turkish-backed militants being deployed from Syria to Yemen to fight alongside pro-Brotherhood forces and against UAE-backed troops and fighters in the Southern Transitional Council. Therefore, although there’s still no sign of any possible alignment between Iranian- and Turkish-aligned forces in Yemen, the common objective of dealing a blow to the Saudi-led alliance and extracting concessions from it appears to have brought the diplomatic positions of Tehran and Ankara closer to each other on the Yemen issue.

A common concern over the potential expansion of Riyadh’s as well as Israel’s regional influence has also contributed to Iranian support for Turkey's position on Libya. While Russia and Syria, both Iran’s partners, back the LNA, the Islamic Republic would prefer to see the consolidation of the Turkish-backed GNA over the empowerment of the Saudi-Egyptian axis in North Africa. Furthermore, Riyadh’s direct and indirect support for the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces with the aim of countering the influence of both Iran and Turkey in Syria, gives Tehran and Ankara another incentive for cooperation.

However, as far as Tehran is concerned, the realignment with Ankara against Riyadh is more tactical, aimed primarily at intensifying pressure on the Saudis to change their approach toward Iran. In this vein, despite reiterating the Islamic Republic’s support for the Turkish-backed authority in Libya, Brigadier General Hussein Dehghan, a military adviser to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, recently stressed Iran's willingness to reconcile with Saudis. “If Saudi Arabia accepts, we are ready to talk to them without any preconditions,” he said in an interview on June 22.

A day after Dehghan’s interview, the Houthis announced a new set of missile and drone strikes against Saudi defense ministry compound and other military targets in Riyadh. As such, by tightening the grip on Saudi Arabia in the realm of regional diplomacy — through realignment with Turkey — as well as on the ground, Iran appears to be striving, via its own pressure campaign, to force the Saudi leaders into recognizing Iran’s regional status and come to terms with it.

With these dynamics in mind, Turkey’s view of recent convergence with Iran seems to be similarly of a tactical nature. Iran's diplomatic support for the GNA will not only help Ankara legitimize its intervention in Libya, but can also lead to a face-saving solution for Turkey in Syria. Although in the wake of the March 5 ceasefire agreement between Turkey and Russia the situation in Idlib has partially stabilized, the Erdogan government knows that the current status quo is not sustainable in the long run and that the Syrian army and its allies will sooner or later resume a conclusive military operation in the area. Under these circumstances, redeploying armed rebels to Libya and Yemen could, to some extent, relieve Ankara’s concerns over the possibility of those mostly Islamist rebels entering the Turkish territory and posing a security threat to their own sponsor. Meanwhile, by shrinking the chances of an all-out proxy conflict, the move would increase the likelihood of a compromise between Turkey, Iran and Russia in Syria. This does not yet mean that fundamental differences between Iran and Turkey in the region, especially in Syria, will be quickly, let alone automatically, resolved.

Rather than herald the emergence of a new alliance in the region, the recent rapprochement between Iran and Turkey appears to be a marriage of convenience, aimed at securing separate interests for each party. Factors such as the possibility of enhanced coordination between Ankara and Washington in Syria, a potential detente between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and Tehran’s desires not to alienate Russia by taking a more proactive position against Khalifa Haftar — could negatively affect the new Iran-Turkey realignment.