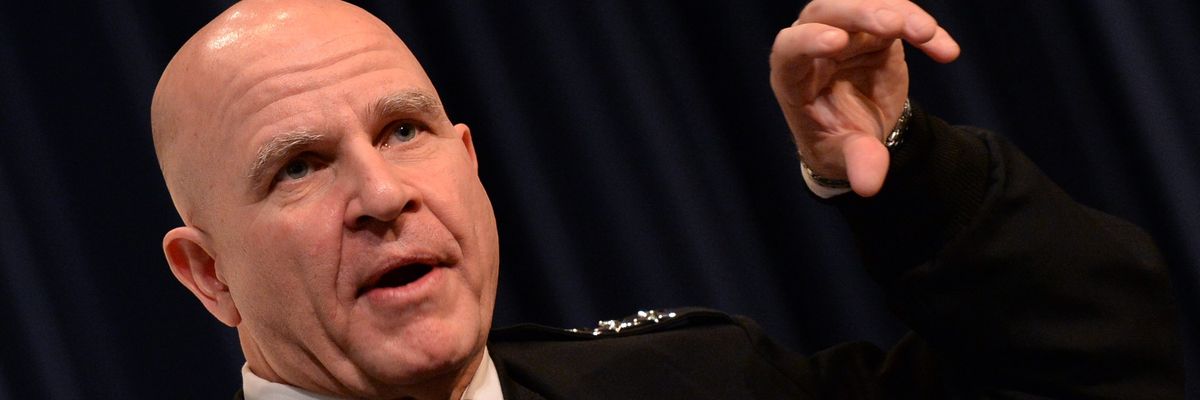

H.R. McMaster looks to be one of those old soldiers with an aversion to following Douglas MacArthur’s advice to “just fade away.”

The retired army three-star general who served an abbreviated term as national security adviser has a memoir due out in September. Perhaps in anticipation of its publication, he has now contributed a big think-piece to the new issue of Foreign Affairs. The essay is unlikely to help sell the book.

The purpose of McMaster’s essay is to discredit “retrenchers”—that’s his term for anyone advocating restraint as an alternative to the madcap militarism that has characterized U.S. policy in recent decades. Substituting retrenchment for restraint is a bit like referring to conservatives as fascists or liberals as pinks: It reveals a preference for labeling rather than serious engagement. In short, it’s a not very subtle smear, as indeed is the phrase madcap militarism. But, hey, I’m only playing by his rules.

Yet if not madcap militarism, what term or phrase accurately describes post-9/11 U.S. policy? McMaster never says. It’s among the many matters that he passes over in silence. As a result, his essay amounts to little more than a dodge, carefully designed to ignore the void between what assertive “American global leadership” was supposed to accomplish back when we fancied ourselves the sole superpower and what actually ensued.

Here’s what McMaster dislikes about restraint: It is based on “emotions” and a “romantic view” of the world rather than reason and analysis. It is synonymous with “disengagement”—McMaster uses the terms interchangeably. “Retrenchers ignore the fact that the risks and costs of inaction are sometimes higher than those of engagement,” which, of course, is not a fact, but an assertion dear to the hearts of interventionists. Retrenchers assume that the “vast oceans” separating the United States “from the rest of the world” will suffice to “keep Americans safe.” They also believe that “an overly powerful United States is the principal cause of the world’s problems.” Perhaps worst of all, “retrenchers are out of step with history and way behind the times.”

Forgive me for saying so, but there is a Trumpian quality to this line of argument: broad claims supported by virtually no substantiating evidence. Just as President Trump is adamant in refusing to fess up to mistakes in responding to Covid-19—“We’ve made every decision correctly”—so too McMaster avoids reckoning with what actually happened when the never-retrench crowd was calling the shots in Washington and set out after 9/11 to transform the Greater Middle East.

What gives the game away is McMaster’s apparent aversion to numbers. This is an essay devoid of stats. McMaster acknowledges the “visceral feelings of war weariness” felt by more than a few Americans. Yet he refrains from exploring the source of such feelings. So he does not mention casualties—the number of Americans killed or wounded in our post-9/11 misadventures. He does not discuss how much those wars have cost, which, of course, spares him from considering how the trillions expended in Afghanistan and Iraq might have been better invested at home. He does not even reflect on the duration of those wars, which by itself suffices to reveal the epic failure of recent U.S. military policy. Instead, McMaster mocks what he calls the “new mantra” of “ending endless wars.”

Well, if not endless, our recent wars have certainly dragged on for far longer than the proponents of those wars expected. Given the hundreds of billions funneled to the Pentagon each year—another data point that McMaster chooses to overlook—shouldn’t Americans expect more positive outcomes? And, of course, we are still looking for the general who will make good on the oft-repeated promise of victory.

What is McMaster’s alternative to restraint? Anyone looking for the outlines of a new grand strategy in step with history and keeping up with the times won’t find it here. The best McMaster can come up with is to suggest that policymakers embrace “strategic empathy: an understanding of the ideology, emotions, and aspirations that drive and constrain other actors”—a bit of advice likely to find favor with just about anyone apart from President Trump himself.

But strategic empathy is not a strategy; it’s an attitude. By contrast, a policy of principled restraint does provide the basis for an alternative strategy, one that implies neither retrenchment nor disengagement. Indeed, restraint emphasizes engagement, albeit through other than military means.

Unless I missed it, McMaster’s essay contains not a single reference to diplomacy, a revealing oversight. Let me amend that: A disregard for diplomacy may not be surprising in someone with decades of schooling in the arts of madcap militarism.

The militarization of American statecraft that followed the end of the Cold War produced results that were bad for the United States and bad for the world. If McMaster can’t figure that out, then he’s the one who is behind the times. Here’s the truth: Those who support the principle of restraint believe in vigorous engagement, emphasizing diplomacy, trade, cultural exchange, and the promotion of global norms, with war as a last resort. Whether such an approach to policy is in or out of step with history, I leave for others to divine.

This article has been republished with permission from The American Conservative.