On 9 May, the second anniversary of the US withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal, or Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), Secretary of State Mike Pompeo tweeted that ‘Americans are safer and the Middle East is more peaceful than if we had remained in the #JCPOA’. Any way one looks at it, this is demonstrably untrue. The truth is the opposite.

On the nuclear front, President Donald Trump’s withdrawal prompted Iran to suspend its adherence to all of the limits imposed by the JCPOA, something the Trump administration thought was unlikely. In September 2018, a senior administration official told the International Crisis Group that the US could ‘have our cake and eat it too’, in other words, violate the agreement while Iran abided by it. Continuing to uphold those limits, as Iran did up until a year ago, would have meant it remained at least a year away from being able to produce a weapon’s worth of highly enriched uranium. Instead, the so-called breakout period is now about six months.

Iran has not pulled out of the deal entirely. It still accepts the enhanced inspection requirements and participates in the oversight mechanisms of the JCPOA. It also pledges to return to full compliance if it receives the economic benefits provided for in the accord.

On the peace front, over the past year, Iran has attacked Saudi oil facilities, seized tankers, sabotaged other oil tankers, fired ballistic missiles at a joint US–Iraqi base, and reportedly encouraged militia groups that have repeatedly attacked US forces in Iraq. All of this malicious activity stems from the breakdown in relations that Trump instigated. The region is less peaceful and Americans less safe as a consequence.

On the economic front, Trump’s re-imposition and reinforcement of nuclear-related sanctions has certainly weakened Iran. Oil exports have fallen from 2.5 million barrels per day to a few hundred thousand, which it has to sell at a discount below the already depressed global price. The economy shrank by 7.65% in 2019 and is projected to fall another 6% this year. Iran’s unprecedented request for US$5 billion of emergency funding from the International Monetary Fund to fight the coronavirus pandemic remains under discussion amidst US efforts to block it. Causing economic duress is the only metric by which Trump and his enablers have any grounds for claiming tactical triumph. But how bleeding Iran makes Americans safer and the region more peaceful defies logic.

Theoretical consequences of Iran’s economic duress

Two imaginative theories are proposed. The first is that economic duress will cause the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) to give way to a regime that is democratic, peace-loving and pro-American. According to Trump associates, such as his personal attorney Rudy Giuliani and former national security advisor, John Bolton, the exiled Mujahedin-e-Khalq group (MEK) is the ideal vehicle for this would-be miraculous transition, even though the MEK is neither democratic nor peaceful, has a record of terrorism and near zero support in Iran itself.

Fundamentalist opponents of the IRI are fond of fearmongering claims that Iran is on the verge of economic collapse and have repeated this incessantly for over two years. But having lived under sanctions for four decades, Iranians have acquired resilience. Moreover, the institutions that bind the IRI together – the conservative clergy, the Islamic Republican Guard Corps (IRGC), the courts and the other elements of the security apparatus – remain as firmly in control as ever. In the unlikely event that regime change were to transpire, the new leadership would almost surely come from the ranks of these groups. Iran would be even more vengeful and antagonistic.

A more sophisticated, but equally mistaken, theory behind the ‘bleed Iran’ policy rests on the notion that war with the IRI is inevitable sooner or later. In anticipation of this coming conflict, the argument goes that it is best to weaken Iran now in whatever way possible. Maximum pressure is thus designed to force Iran not to the bargaining table, but to the beggar’s bush.

The obvious fallacy behind this line of thinking is that war is by no means inevitable, but acting as though it is can make conflict a self-fulfilling prophecy. In the absence of a US provocation, Iran has no reason now, or in the future, to attack the US or its forces. This is not to absolve Iran for the deaths it has caused to many American soldiers in Iraq over the years, nor to suggest that the IRGC is a benign organisation – it is deadly and ruthless. The IRGC, however, does not threaten the US homeland. The very real differences that the US has with Iran can be addressed through peaceful means of diplomacy, coalition-building and deterrence, the latter backed by the proportionate use of force as needed.

Among these tools, the Trump administration prioritises physical threats, giving short shrift to negotiation and partnerships. Yet Iran hardly seems deterred, as witnessed by its harassment of US warships in the Gulf last month.

Pompeo’s false boast that Americans are safer and the Middle East more peaceful as a result of Trump’s move two years ago is pure propaganda. Withdrawing from the JCPOA was an atrocious foreign-policy mistake.

This article has been republished with permission from the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

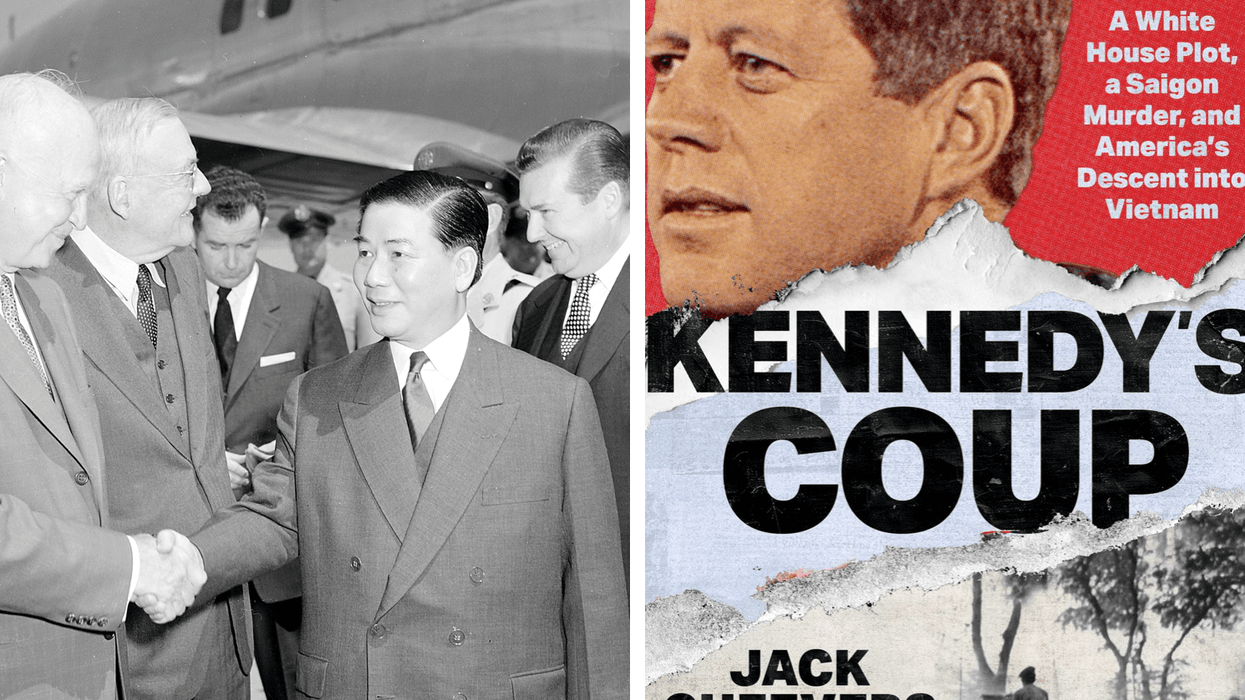

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)