It has become a cliché to lament the demise of the rules-based multilateral world order. But Columbia University professor Jeffrey Sachs introduced an important nuance into this debate at a conference at the Vatican in February 2020, claiming that it is not so much the multilateralism that is being challenged globally as it is the deliberate policy of the United States under the President Donald Trump to weaken it.

One may qualify this statement by recalling that Trump is not alone in undermining multilateralism: Russian President Vladimir Putin’s policies in what Kremlin calls its “sphere of influence” in the former Soviet Union, or the regional adventurism of mini-Trumps, such as the Israeli Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman also contribute to the erosion of rules-based world order. However, given the power of the United States, it is undeniable that Trump’s “America First,” which Sachs calls a “vulgar form of American exceptionalism,” presents greater danger to the world than the actions of his emulators elsewhere.

“America First,” however, is ultimately self-defeating. In the worldview of Trump and his advisers there can only be winners and losers. Alliances and norms have no intrinsic value in themselves. Every relationship is transactional and useful only insofar as the United States is able to extricate more advantages from it than the other side. As a result, the U.S. foremost alliance since the World War II – with Europe – is fraying.

The outbreak of the novel coronavirus could have served as an opportunity for the Trump administration to rediscover the value of international cooperation in fighting this global disease. However, the opposite happened: it only reinforced Washington’s unilateralist instincts. This is highlighted by such actions as an abrupt cutting of funding for the World Health Organization (WHO), and seizing of Germany-bound medical equipment from Asia. Germany’s interior minister called it an “act of modern piracy.”

These steps compound the earlier affronts such as a blanket ban on European travel to the U.S. and recrudescence of sanctions against Iran and Venezuela at a time when the European Union (EU) is working on mitigating the impact of the pandemic on these countries.

The effect these actions produce, however, is not Europe kneeling down to American demands on every occasion. Rather, it is learning, painstakingly, to live past the United States. The EU slammed Trump’s decision to cut WHO as unjustified. And as soon as it was announced, Finland stepped in and pledged additional resources.

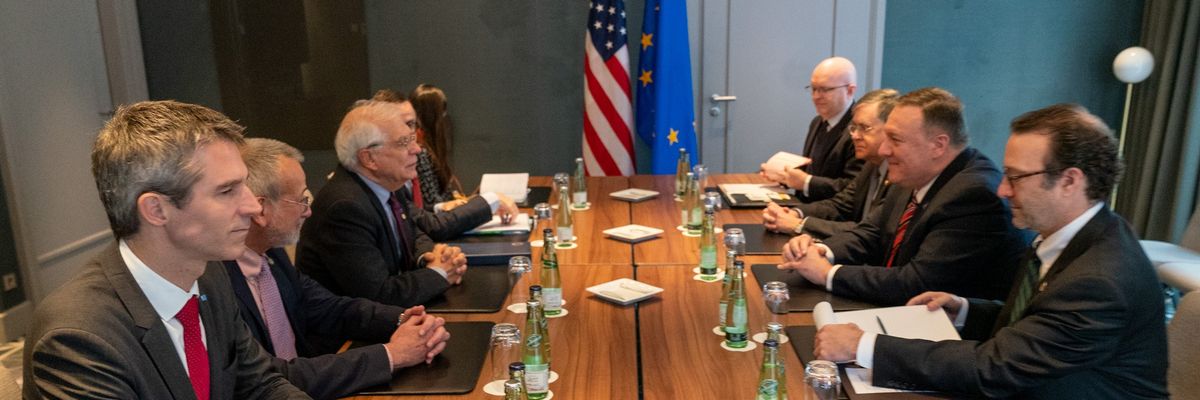

On Iran, the U.S. “maximum pressure” campaign is isolating Washington more than Tehran. Addressing the meeting of the EU foreign ministers on April 22, EU Minister for Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell regretted that the U.S. was preventing the International Monetary Fund (IMF) from approving Iran’s emergency loan request to fight the pandemic — a request that the EU supported.

A few days earlier, in an exchange of views in the European Parliament, Borrell questioned the assurances of U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo that the humanitarian trade with Iran was exempt from American sanctions by noting that this was “not what the economic operators believed.” This was an obvious reference to the obstacles financial entities face in processing Iran-related transactions, out of fear of American extra-territorial sanctions.

On a deeper level, Borrell signaled a fundamental divergence with the American approach to sanctions as a tool of statecraft: from the European perspective, sanctions are designed to voice a disapproval of specific policies, and therefore are targeted at individuals. They are not directed at inflicting misery on civilian populations in the hope that they will rise up against the regimes, an assumption that seems to guide the American sanctions policy against both Iran and Venezuela.

As important as these political messages are, they also spurred concrete actions to safeguard European interests. It is easy to deride INSTEX, the special trade mechanism with Iran devised by Britain, France, and Germany that took almost two years to become operational. What is relevant is that Washington’s weaponization of its dominance of the world financial markets to impose its policy preferences is pushing the Europeans to find ways to emancipate themselves from this dominance.

The fact that more European countries joined INSTEX is a sign of confidence in this route. Contrast this with the failed summit in Warsaw in January 2019, where Pompeo tried to woo Europeans into an anti-Iranian coalition. Trump’s impulsive threats, at a time of global pandemic, to “shoot down all and any Iranian speedboats harassing the U.S. navy” and his endorsement of a fake twitter account managed by the disgraced Iranian opposition cult Mojaheddeen-e Khalk (MEK) are only driving the U.S. and EU further apart.

The same logic applies to the U.S.-Europe-China triangle. It is true that lately some European governments, with France and Britain at the vanguard, toughened their rhetoric up on China, demanding more transparency on the origins of COVID-19. There is also a growing unease over the Chinese propaganda efforts aimed at exalting Beijing’s handling of the crisis at the expense of the “decadent” European democracies. Chinese officials also didn’t do themselves any favors by disseminating dark conspiracy theories about the origins of the coronavirus. This builds on the pre-existing concerns over Chinese takeovers of European infrastructure and industrial assets.

However, these concerns are balanced by a clear realization in Europe of the need of Chinese cooperation not only in fighting the pandemic, but also on a whole array of other issues, such as climate change, global financial governance, and sustainable developments goals, to name but few.

Currently it’s China, not the U.S., that is working with the EU in multilateral frameworks on meeting these challenges. Also, economic recession and Asia-originated supply chains of medical products dictate caution in EU’s approach to one of the bloc’s key economic partners.

Washington, by contrast, seems to have entered into a Chinese-bashing mode. Trump and Pompeo for weeks insisted on calling the COVID-19 a “Chinese virus.” Infamously gung-ho senator and Trump ally Tom Cotton, backed by other hawks, is calling for a confrontation with China. Meanwhile, Trump’s Democratic challenger Joe Biden appears to be trying to out-hawk the president on China.

This doesn’t bode well for the future of multilateralism or transatlantic relationship. If there is something most experts agree on it’s that the post-pandemic world will see an intensification of American-Chinese rivalry. By choosing an “America First” brand of exceptionalism and showing haughty disdain to the views and interests of its allies, the United States risks entering this new era in a much weakened position.

This article reflects the personal views of the author and not necessarily the opinions of the S&D Group and the European Parliament.