After months of will-they-won’t-they speculation, the Xi Jinping-Joe Biden summit in San Francisco next week is on. Unless of course some black swan should spoil the diplomatic inertia drawing the two leaders together.

After jumping the hosting queue to take on the convening duties for this year’s Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Economic Leaders’ Meeting, the U.S. has now guaranteed that its own agenda for the summit — supply chain resilience, digital trade, connectivity, small and medium-sized enterprises, climate change and sustainability — will be well and truly overshadowed by the focus on the face-to-face between the two most powerful leaders in the world. The sideline session will be the main event.

In the world of “omnicrisis” — in particular, the Ukraine conflict and the Israel-Hamas war and siege of Gaza, and the global challenge of climate change — China and the U.S. have to be in communication, settled into a working rivalry based on the Biden administration’s “three Cs” framework of cooperation, competition and confrontation. Washington and Beijing are both an indispensable partner and an inevitable adversary — they can and will clash, even in a manner reminiscent of the brinkmanship of the Cold War, but for global stability, peace and environmental sustainability, they must work together on critical international crises, or at least talk about them.

A China-U.S. war, which strategists in both countries have spent countless hours gaming out, would be a meaningless contest, with no winner, only losers and unfathomable collateral damage.

Biden and Xi could have met in September at the G20 summit in Delhi, but Xi was a no-show — possibly to avoid a visit to India, the geopolitical belle-of-the-ball with which China has a bubbling border dispute. More likely he needed instead to attend to urgent domestic matters such as China’s weak economy and troubles with two disappeared ministers who were eventually sacked. The Chinese have remained officially non-committal about Xi’s attendance at APEC too, but Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s two-day October visit to Washington, capped by an hour-long encounter with Biden at the White House, has apparently confirmed the appointment.

Both sides appear willing to keep the tête-à-tête on track. For one thing, the stream of high-level contacts since Secretary of State Antony Blinken went to Beijing in June, a visit postponed by the “spy balloon” brouhaha, has continued unabated. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen was in China shortly after, followed by Biden’s climate envoy John Kerry. Commerce chief Gina Raimondo, the administration’s point person on economic sanctions and trade restrictions, arrived in August.

There have been telling cameo appearances, too. In July, centenarian Henry Kissinger flew in to be celebrated as an “old friend” by the Chinese leadership including Xi. In October, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer led a bipartisan congressional delegation to Beijing, meeting Xi two days after the surprise attack on Israel by Hamas terrorists.

Later in the month, California Governor Gavin Newsom breezed through China on a tour pointedly focused on climate change. Widely regarded as a presidential hopeful, Newsom was the first American governor to visit China in over four years and the first to be received by Xi in over six years.

Signs that China is eager for the Biden-Xi meeting to go ahead and for the two countries to put their relationship on a more productive footing have been discernible. Wang Yi has been meeting for hours of talks with both Blinken and Biden national security adviser Jake Sullivan at different venues around the world. Besides receiving American officials in Beijing, China has reciprocated with visits to the U.S. by Commerce Minister Wang Wentao in May, Wang Yi at the end of October, and on the eve of the APEC meeting Vice Premier He Lifeng, Yellen’s counterpart.

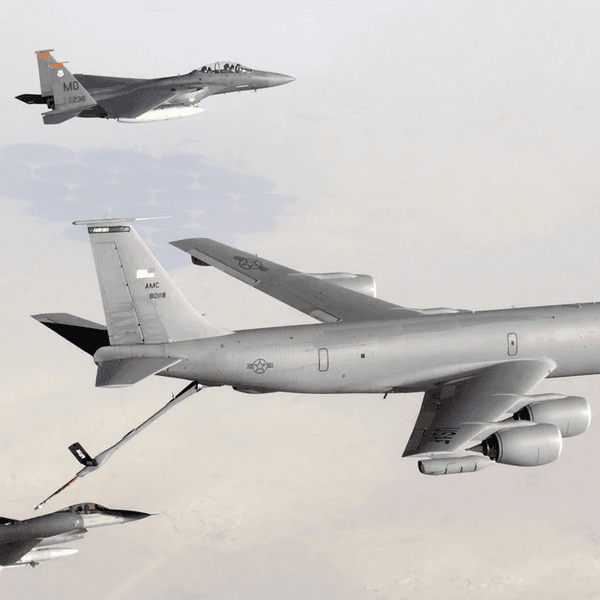

But possibly the most significant re-engagement move so far was the resumption of defense contacts at the end of October when Chinese and American officials met briefly at a multilateral security forum in Beijing. The U.S. had been trying to restart military-to-military talks which China cut off after then-Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan in August 2022. American Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin had reached out to his counterpart Li Shangfu, also a U.S.-sanctioned individual, requesting a meeting on the sidelines of a conference in Singapore in June, but was refused. Li was removed from his position on October 24. Austin has requested a meeting with his yet-unnamed counterpart at an ASEAN defense ministers gathering in Jakarta on November 16.

Where does all this put the China-U.S. relationship? There is little expectation that the Biden-Xi meeting will yield any significant outcome. When they met in Bali in November 2022, the two had discussed “guardrails” to prevent the contentious relationship from deteriorating into conflict. Some of those preventive mechanisms are now in place. The two governments launched working groups on economic and financial issues in September, with the former meeting for the first time by video conference on October 24.

Both groups are supposed to convene again when Yellen and He confer in San Francisco on November 9-10.

The diplomatic exchange between China and the U.S. is arguably the highest and broadest since the eighth and final round of the bilateral Strategic and Economic Dialogue (S&ED) in 2016. The S&ED was a series of senior-level discussions launched in a limited format during the George W. Bush administration and expanded in 2009 by Barack Obama.

While the two nations are not yet back to that level of engagement, the launch of mechanisms for regular consultations goes against the persistent narrative of utter negativity. To be sure, the two sides may be talking at cross purposes, merely airing grievances. China is seeking relief or at least a pause from all the sanctions and exclusions, particularly on advanced technology transfer and financial flows.

The U.S., however, is unlikely to comply, especially with the 2024 election campaign already underway. One of Beijing’s demands for Xi’s presence in San Francisco is for Washington to refrain from announcing fresh trade restrictions before, during or soon after the Biden meeting.

Other complications are on the horizon. Some regional analysts argue that Beijing will want to challenge Washington at this geopolitically fraught time. But the Chinese are no less stretched diplomatically and, more to the point, are facing serious economic challenges at home.

The Taiwan presidential election in January will surely be preceded and followed by the mainland’s customary military menacing. Washington’s drift away from its traditional ambiguity on defending the island is the biggest irritant in China-U.S. relations. Actions by both China and the Philippines in the South China Sea have raised fears of a conflict that could draw in the U.S., which has a mutual defense treaty with Manila.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong is planning on passing more security laws in the first half of 2024. As the U.S. elections approach, the political rhetoric and policy making in Washington are likely to get more performative and provocative.

This is not (yet) a G2 world, but Xi and Biden could capture imaginations by together engineering a diplomatic masterstroke in San Francisco if they were to announce a trio of cooperative projects: first, a joint effort to convene relevant parties to resolve the Israel-Hamas war and set a pathway to a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; second, a collaborative initiative to bring peace to Ukraine; and third, an agreement to catalyze countries to increase commitments at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai in December.

And while they are at it, they should endorse rebounding post-pandemic bilateral cultural and educational exchange (Washington can reinstate the Fulbright program with Hong Kong and the mainland), renew the U.S.-China science and technology agreement set to expire early next year, and reboot China’s program to loan pandas to American zoos. An impossibility? Optimists in these dire times should dare to dream.

- Why this Biden-Xi Summit won't be good enough - Responsible Statecraft ›

- Renewed climate cooperation a win for US-China relations and the planet - Responsible Statecraft ›

- The lost opportunity of the Biden-Xi meeting - Responsible Statecraft ›

- COP28: An occasion for honest stocktaking on action over climate change - Responsible Statecraft ›

- Could Taiwan election make US-China relations worse? | Responsible Statecraft ›

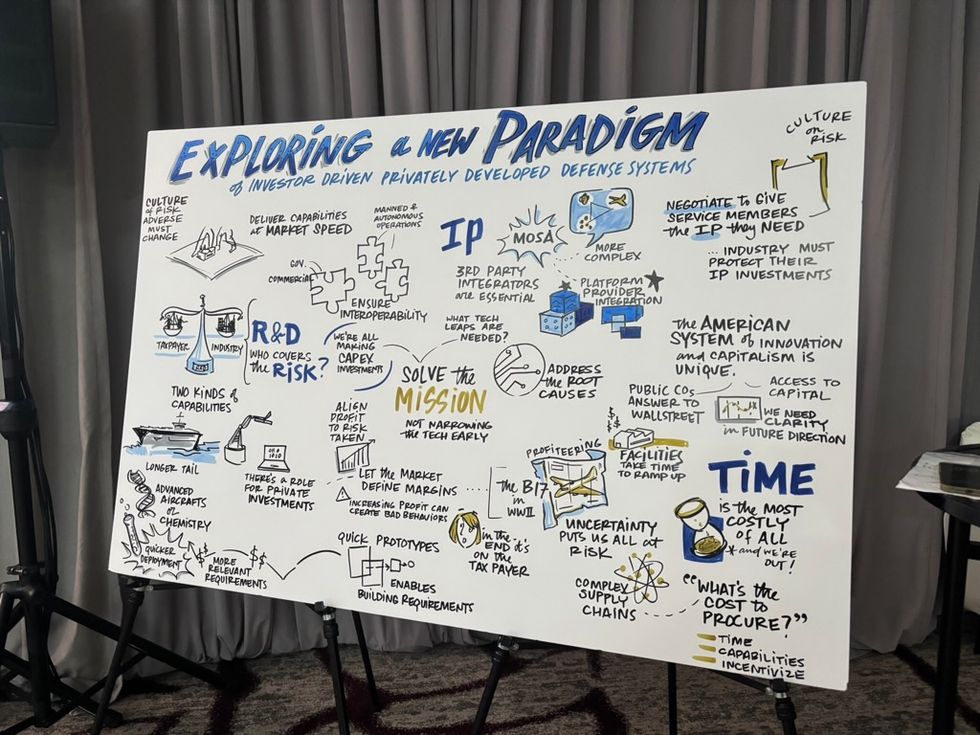

(Shana Marshall)

(Shana Marshall)