New York Times columnist Paul Krugman is very smart and he knows a lot about markets, politics, and media. Among Krugman’s many job titles and awards covering these topics throughout his illustrious career, he was a professor at both Princeton and MIT and he won the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Based on the content of his latest column, however, when it comes to U.S. foreign policy, Krugman appears to fall victim to a common occurrence among many in the elite media: relying on World War II era notions of American exceptionalism that ultimately promote hawkish, neocon, or militaristic policies toward a non-analogous present day issue.

There are many recent examples of this phenomenon, starting most obviously with the run up to the war in Iraq. Corporate and mainstream media (for the most part) lined up dutifully behind George W. Bush’s crusade to rid the world of Iraq’s purported WMD, liberate the Iraqi people, and help spread American style democracy throughout the Middle East and beyond.

Bush and his media allies regularly invoked memories of World War II to justify the post-9/11 U.S. wars in Afghanistan and then Iraq. “In some ways, this struggle we're in is unique,” Bush said in 2004 referring to both wars. "In other ways, it resembles the great clashes of the last century between those who put their trust in tyrants and those who put their trust in liberty. … Like the Second World War, our present conflict began with a ruthless surprise attack on the United States."

“Although I dislike the modern tendency to compare every mad dictator to Hitler, in this narrow sense, the comparison to Saddam might be apt,” journalist Anne Applebaum wrote at the time.

And of course, if you opposed the U.S. war in Iraq then, you were accused of being an “appeaser” like British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who signed away Czechoslovakia to Hitler in the late 1930s.

Somewhat ironically, most historians argue that it was actually the Soviet Union, not the United States and Great Britain, that ultimately tipped the scales against Nazi Germany, as the European theater of the Second World War was largely fought on the Eastern Front. But any casual consumer of Hollywood products like “Saving Private Ryan” or “Band of Brothers,” or any World War II themed program on the History Channel might be led to believe that the United States far and away saved the day.

Of course the United States played a major role in defeating Hitler, but the narrative of America as World War II’s sole superhero is very much part of Americans’ perception of themselves and their history. That narrative also seems to feed the notion of American exceptionalism — that the U.S. can, in part, liberate the world from tyranny by force if necessary — which pervades the elite media psyche when it comes to covering and talking about U.S. foreign policy.

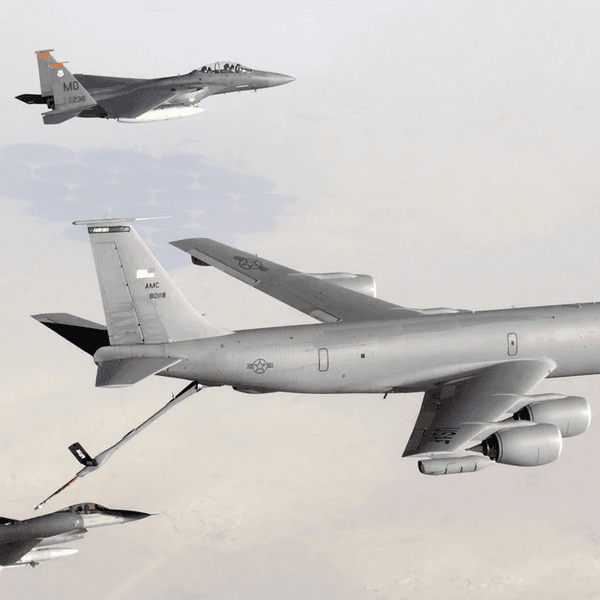

Take another more recent example — in one particular incident shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, White House reporters appeared to default to this notion that American military power could be applied to end the conflict. They continually peppered then-Press Secretary Jen Psaki about why the Biden administration wasn’t doing all it could militarily in Ukraine, including establishing a no-fly zone, which would have amounted to a direct U.S. war with Russia.

“Why does the U.S. believe they know better what Ukraine needs than what Ukrainian officials are saying they need the most?” one reporter wondered.

“Is the president showing enough strength against Putin?” asked another.

A third White House reporter asked: “Would a strike in Poland on supplies, or anything really, automatically be met with a military or forceful response?”

This gets us back to Krugman.

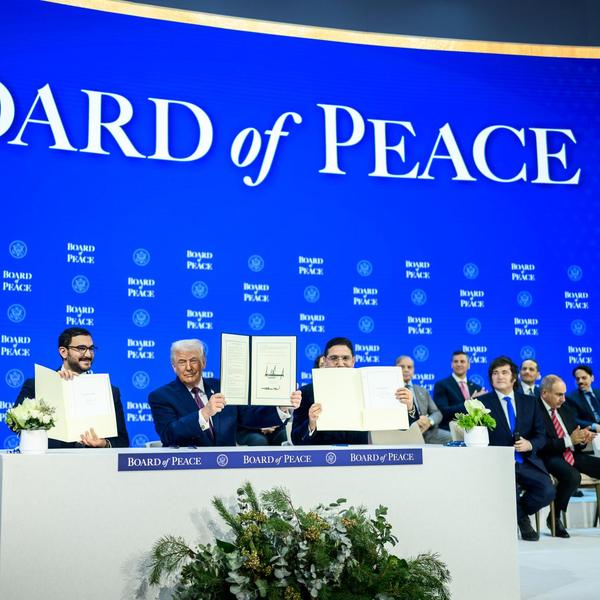

Pivoting off this week’s 79th anniversary of the Allied invasion of Europe, Krugman called the coming (or already underway) Ukrainian counteroffensive “the moral equivalent of D-Day.” As such, he lamented that Americans and other citizens of Western democracies are not “fully committed to Ukrainian victory and Russian defeat” and that only a minority of Americans are willing to send aid to Ukraine “for as long as it takes.”

It’s certainly true that Putin is a bad guy and the Ukrainians’ cause is just in the same sense that Hitler was also a bad guy and the Allied cause just. But in this case Krugman doesn’t define Ukrainian victory or Russian defeat. In reality, while some argue that Russia has already been defeated, a “total defeat” for Russia is far murkier.

Moreover, if victory for Ukraine means kicking Russia out of all occupied territories, then the case for continued U.S. aid gets a bit trickier. For example, the U.S.’s highest ranking military officer has said that it’s unlikely that Ukraine will achieve this outcome in the near future. Other experts say that Ukraine regaining control of all lost territory is “a highly unlikely outcome.”

From that vantage point, aiding Ukraine for “as long as it takes” looks fairly indefinite and thus a little more complicated.

Krugman later muddies the waters a bit on the outcome he’s talking about, referring to the success of the counteroffensive (again success undefined) rather than outright victory in the war (perhaps he’s conflating the two, it’s unclear). Either way, the stakes are “now very high” because … the future of democracy is on the line?

“The point is that the stakes in Ukraine right now are very high. If Ukraine’s counteroffensive succeeds, the forces of democracy will be strengthened around the world, not least in America. If it fails, it will be a disaster not just for Ukraine but for the world. Western aid to Ukraine may dry up, Putin may finally achieve the victory most people expected him to win in the war’s first few days, and democracy will be weakened everywhere.”

It’s again unclear what democracy in the United States, or anywhere else outside Ukraine for that matter, has anything to do with the war in Ukraine. Regardless of the outcome, the United States and other countries with democratic systems will remain democracies.

But ultimately, Krugman’s meandering logic follows a problematic pattern among many in the media whose historical reference point will always be World War II and in turn believe the United States can apply that experience to any other world problem no matter how dissimilar or unrelated it is, or whether even a military solution is required.

The reality is that the war in Ukraine is not going to end with Putin committing suicide in a bunker somewhere in Moscow, and Russian troops aren’t likely to be beaten back to Ukraine’s 2014 border. The war in Ukraine isn’t World War II so perhaps those prominent figures who feel compelled to offer their way forward should do so with a little more humility … and restraint.

(Shana Marshall)

(Shana Marshall)