The increase in anti-Asian hate crimes related to the rhetoric around the novel coronavirus pandemic is alarming from civil liberties and human rights perspectives. But the marginalization of Asian Americans has a negative impact on U.S. national security as well.

At a time when we need more people who understand East Asia to make informed policy decisions due to the region’s pivotal strategic importance, recruiting and retaining a government workforce with the right linguistic and cultural skills is a national security imperative. But anti-Asian bigotry coming from the very top of the U.S. government risks driving away those Americans the U.S. national security apparatus needs the most right now.

The Foreign Service Institute categorizes Chinese-Cantonese, Chinese-Mandarin, Japanese, Korean, and Arabic as the most difficult languages to learn, requiring 2,200 hours of State Department-sponsored language training compared to the 600 hours required to master easier languages. Recruiting and retaining those with native fluency, including foreign-born immigrants, saves time and resources.

Yet for years, Asian Americans at the State Department have struggled to get assigned to countries where their language skills would be used due to fear of foreign influence. There are documented cases where Asian American diplomats faced lingering distrust about their “American-ness,” which is devastating for diplomats whose job is to represent the United States.

As Khanh Nguyen, a U.S. Foreign Service officer and former vice president of the Asian American Foreign Affairs Association, points out, “questions of loyalty and patriotism have a disproportionate impact on U.S. government officials of Asian descent.”

Absent more transparency in the assignment process, Asian American diplomats may continue to be under-utilized and overlooked for roles where their skills can further diplomacy. Many may choose to leave government service. Others may feel repelled by the stigmatization of Asian Americans and chose not to serve in the first place.

To understand the value of linguistically- and culturally-fluent experts to guide U.S. national security, one needs to look no further back than the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. The absence of a diverse national security workforce likely contributed to miscalculations and blind spots. Had Middle East expertise not been scorned and belittled by neoconservatives at the time, the ruinous Iraq war could perhaps have been avoided altogether. Once the war started, though, the lack of expertise became all the more costly. As Central Intelligence Agency Station Chief (ret.) Haviland Smith observed, the U.S. intelligence community prior to 9/11 suffered from an acute shortage of Arabic speakers and staff in-country to help “maintain relations with trusted local liaisons [that] are crucial to the agency’s mission.”

According to a study by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) of the U.S. Army, the Department of State, the Department of Commerce, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s workforce in 2001, these agencies lacked diplomats and intelligence specialists in hard-to-learn languages from the Middle East, “weakening the fight against international terrorism.”

The GAO also noted that those implementing policies abroad often lacked language skills that impeded intelligence gathering and diplomatic affairs. For instance, the U.S. Army had only half of the Arabic translators that it was authorized to fill through 2001, and only a third of Farsi speakers. In 2003, the U.S. Central Command admitted that “the U.S. Army does not have a fraction of the linguists required to operate in the Central Command area of responsibility.” A 2007 study found that only 33 spoke Arabic among the 1,000 people who worked in the U.S. Embassy in Iraq.

The dearth of linguistic skills in the U.S. government at the time should perhaps not be very surprising, mindful of the systematic religious profiling and surveillance they faced after 9/11 despite the absence of independent evidence of entrenched extremist activities among Americans of the Islamic faith. And this happened at a time when the political class pushed back against bigotry targeting Americans of Middle Eastern descent. Only six days after the 9/11 attacks, President George W. Bush gave a speech at the Islamic Center of Washington DC renouncing bigotry against Muslim Americans.

Unfortunately, President Donald Trump is not following the same playbook. Instead, the widespread use of “Chinese virus” within the highest levels of government has normalized associating the disease with Chinese people, and indirectly, all East Asians and Asian Americans. (Both the World Health Organization and the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention have warned against stigmatizing people of Asian descent or linking COVID-19 to certain populations or nationalities as far back as 2015.)

So what can be done?

First, the Trump administration should condemn anti-Asian hate crimes and stop using such racialized language when discussing the pandemic. President Trump should authorize an independent assessment of the impact of anti-Chinese rhetoric surrounding COVID-19 on the U.S.’s national security workforce, including the ability to attract hard-to-learn East Asian language speakers in government and ensuring that they do not face unfair bias during the security clearance process. The point isn’t about the origins of the virus — we should leave that to scientists to figure out — but the second-order effects of terms like the “Chinese virus” in American communities.

Second, the Trump administration should stop weaponizing anti-China sentiments in order to advance an anti-China foreign policy. Racist attitudes toward Asians prevent the United States from crafting effective and nuanced strategy toward China and the Asia-Pacific region, while exaggerating the threat from China with inflammatory language feeds into anti-Asian racism in the United States.

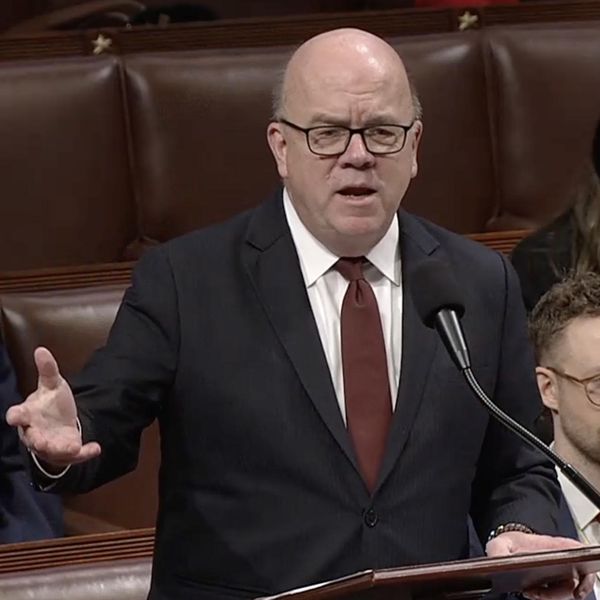

Third, President Trump and Congress should work together to find bipartisan solutions to the challenges facing the Asian American communities due to COVID-19. Thus far, the response has been largely partisan. For instance, H.Res.908, a House resolution condemning all forms of anti-Asian sentiment as related to COVID-19, has 145 cosponsors, of which only one is a Republican. While Democrats and Republicans may differ on matters related to discrimination and civil rights, they should be united against anything that undermines our national security.

Self-interest demands that the U.S. government learn from its past mistakes and build a national security workforce that is equipped to engage the Asia-Pacific. Ignoring this need could make America more susceptible to grave miscalculations and false confidence, leading to more confrontations without a clear strategy.