After a period of relative calm in the aftermath of the shocking murder of Jamal Khashoggi, for which Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has resisted U.S. Congressional and international pressure to link him to the crime, MbS has been back in the news lately. On March 6, reports broke that two senior members of the Saudi royal family – King Salman’s only surviving full brother, Prince Ahmed bin Abdulaziz, and Mohammed bin Salman’s predecessor as Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Nayef, were among a group of princes and officials detained for allegedly treasonous activities.

Almost simultaneously, the OPEC+ meeting chaired by Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, the Saudi energy minister and a much older half-brother to MbS, broke up without extending the Vienna Agreement (on production cuts to stabilize oil prices) reached in December 2016 between OPEC and non-OPEC countries. Oil prices plunged 30 percent as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) matched Russia in responding to the breakdown of the deal by announcing plans to sharply increase oil production.

Many of the details behind the detentions remain murky and speculative, and occurred against the backdrop of a maelstrom of misinformation as rumors spread that the moves to neuter Mohammed bin Salman’s potential opponents signaled that the King was dying or already dead — despite having been photographed only the previous day meeting Britain’s Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab.

Both the timing of and the trigger for the arrests is unclear – why did Mohammed bin Salman feel he needed to act, and why now? Vague initial allegations of treason later appeared to be watered down, while other reports linked the princes to attempts to use the Allegiance Council of senior princes, set up by King Abdullah in 2007 to regulate succession, to attempt to block Mohammed bin Salman’s path to the throne.

The cacophony of speculation from commentators and analysts just as in the dark as everyone else aside, recent and ongoing developments have cast the year-long Saudi presidency of the G-20 into unexpected turmoil and renewed questions over the Crown Prince’s flagship agenda of economic reform.

For a man whose love of the big occasion was spectacularly displayed in his ostentatiously lavish reception of President Trump in May 2017, Mohammed bin Salman was determined to make the most of the Saudi presidency of the G-20, with the November 21-22 leaders’ summit in Riyadh seen as an opportunity to re-emerge onto the international stage after the opprobrium from the Khashoggi murder.

Now, though, Mohammed bin Salman faces the challenge of grappling with the unprecedented global disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the potential that the Trump administration’s chaotic response to the public health crisis in the United States might jeopardize the re-election of a president who has, more than anyone, resisted calls to hold the Saudi leadership to account for Khashoggi’s death.

A sense of self-preservation might prompt Mohammed bin Salman to act to further secure his succession as King while he retains the powerful shield of a protective White House, or while his father still retains the mental faculties to give any such move his blessing. It should be recalled that King Salman served for years as the family “enforcer” and perhaps only someone of his background — a sort of “chief whip” who kept the sprawling Al Saud in line — could have engineered a favored son’s rise to such prominence.

And whereas Salman, with more than fifty years’ experience as Governor of Riyadh and then Minister of Defense, was as respected as much as he was feared, his 34-year-old son appears repeatedly in recent years to have doubled down on coercion perhaps in the absence of widespread consent at his rise.

It is, perhaps, little coincidence that Prince Ahmed was one of three senior princes (and the only one still alive) mentioned with approval in a mysterious royal family letter that sharply criticized Mohammed bin Salman in 2015, or that the removal of Prince Muqrin in April 2015 and later Mohammed bin Nayef in June 2017 established an awkward precedent that the choice of Crown Prince can and may be changed.

Both Mohammed bin Salman and the King may therefore be keen to eliminate any potential challenge to the succession, mindful also of the 84-year-old King’s health and the need to avoid any prolonged situation of illness and uncertainty as in the decade between King Fahd’s debilitating stroke in 1995 and eventual death in 2005.

All this is ultimately a variation of the informed guessing game previously described and may or may not happen as we get nearer the G-20 Summit in November. The most recent arrests will certainly have reminded critics and potential challengers to the Crown Prince of the steep cost of opposing him either publicly or, through close surveillance, even privately.

However, the seemingly arbitrary — and completely unexpected — move against the princes will also have played on existing doubts in many of Saudi Arabia’s political, economic, and security partners about Mohammed bin Salman’s reputation for impulsive, even reckless, decisions.

International investors’ confidence in Saudi Arabia, already fragile after the manner of Mohammed bin Salman’s detention of much of the Saudi business (and royal) elite in the Ritz-Carlton in November 2017, may deal a further blow to anemic levels of foreign direct investment in the Kingdom.

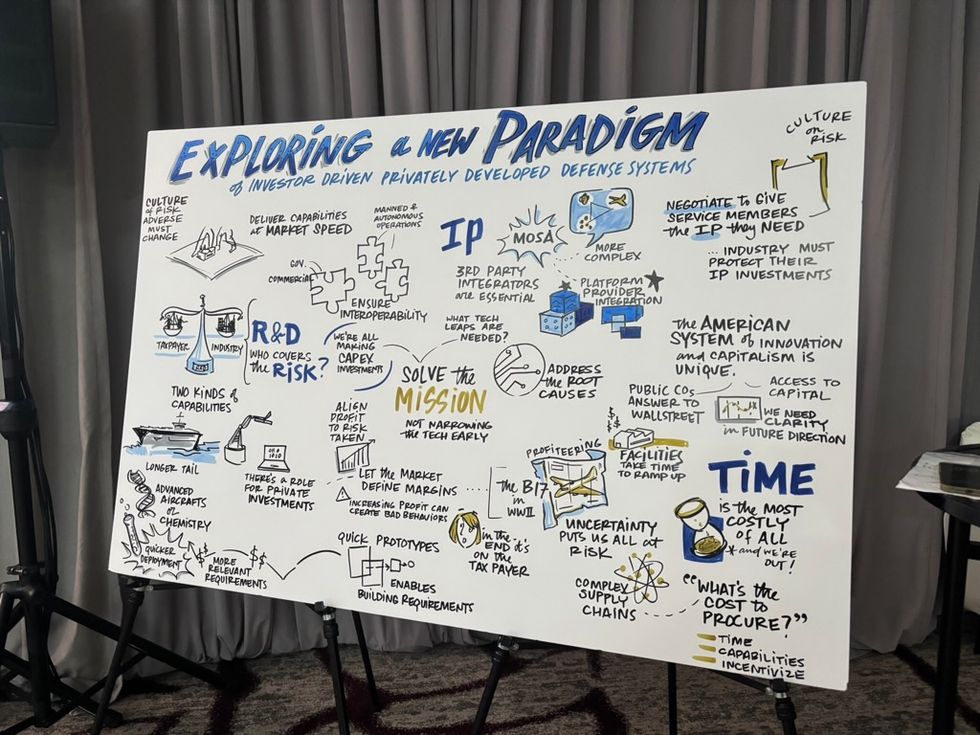

The post-OPEC+ collapse in oil prices and the magnitude of the economic disruption of COVID-19 will put great strain on Mohammed bin Salman’s keynote domestic agenda that he has staked his still-to-be-earned reputation on. Much has been made of the easing of social restrictions in the Kingdom and the popularity of the Crown Prince among young Saudis (although there are no reliable metrics to support this, especially outside of the major cities), but Mohammed bin Salman’s ability to deliver on his promised economic transformation of Saudi Arabia will be his critical test. Having unveiled Vision 2030 with enormous fanfare in April 2016, there is a chance that, by over-promising, Mohammed bin Salman risks under-delivering, as happened with the scaling back of the equally high-profile IPO of Saudi Aramco.

If Mohammed bin Salman really intends to remake the Kingdom his grandfather founded in 1932 (and emulate his 50-year rule), he and the team around him will need to demonstrate their ability to make deep structural changes to the Saudi economy that largely have resisted all previous attempts at reform. In the latest oil war unleashed by the fallout from the OPEC+ breakdown, Mohammed bin Salman may have succeeded in surprising the Russian government by increasing Saudi oil production so rapidly, but he is taking a bold gamble in assuming that Saudi Arabia can survive another era of reduced oil revenues.

Indications that Khalid al-Faleh, the former Minister of Energy who returned to government as head of a new investment ministry on February 25, might be sent to patch up differences with Russian officials, with whom he worked closely in the OPEC+ process, may mean that the oil war, at least, will be short-lived, as survival instincts increasingly take center stage in an ever more unpredictable and volatile landscape.

(Shana Marshall)

(Shana Marshall)