The Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP) expo is the marquee event of the military tech industry. All the big names in the “kill chain-meets-self-checkout” sector gather for this event in the Washington D.C. convention center annually.

Unfortunately I missed this year because they didn’t approve my registration. My article in these pages last year might have something to do with it.

But the military tech folks love a chance to burn fuel and add to their lanyard collection, so there’s always an industry trade event somewhere, usually being dressed up as a workshop/symposia/plenary/TED talk or whatever makes it sound less like war-profiteering. So I packed my bags for an event in the Midwest.

Traditionally, weapons expos are about putting producers in contact with buyers, and they feature large scale sites where companies set up booths to showcase hardware capabilities and include simulations and even live-fire demonstrations. In these spec-ops safe-spaces, government procurement officials and top brass could brush elbows with warlords and mercenaries to take turns shouldering JAVELINs and downing batch bourbons. But with the introduction of more Silicon Valley tech firms into the MIC, many industry gatherings feature asset managers and investors from venture capital and private equity firms who care less about the specs than the ROI.

Gone are the “booth babes” of yesteryear, replaced by baby-faced billionaires in Patagonia quarter zips. Spurred on by the advent of ZIRP (zero-interest rate policy), allowing investors to borrow money essentially for free, and the decline of consumer-focused tech products, investors have turned their focus to military markets. Along with the traditional range of executives from the legacy military contractors, specialized suppliers, and government officials, the real guests of honor are venture capital investors and reactionary techno-solutionists.

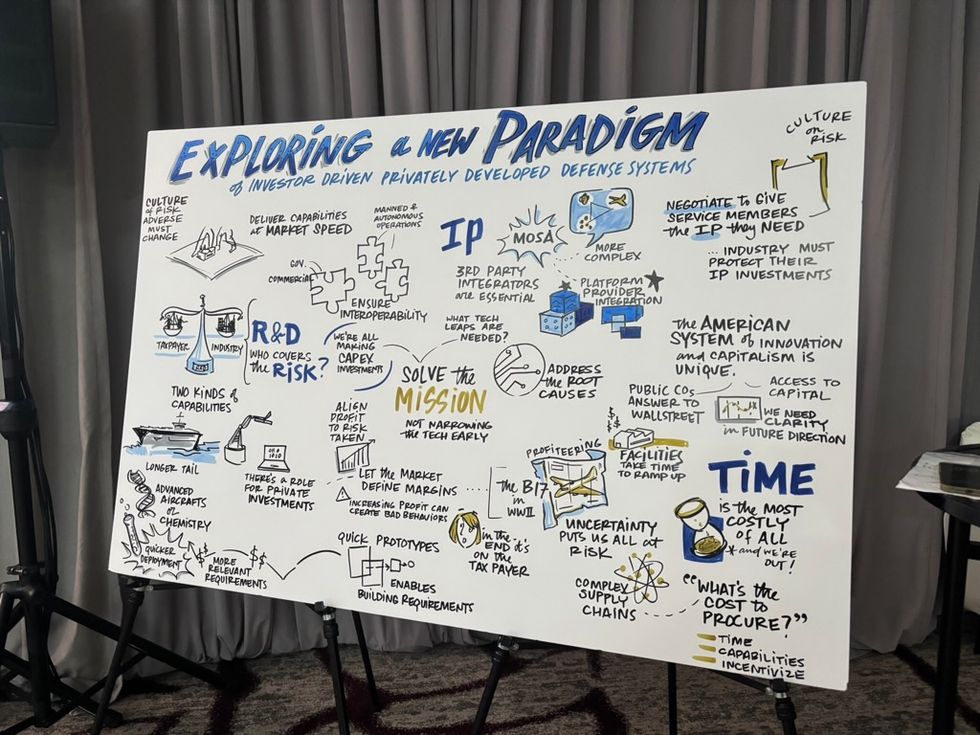

And these characters bring a whole new aesthetic. The space at the Creative Disruptors By The Lakes expo in Minnesota last fall was low on tactical accessories and patriotic insignia and big on dark enlightenment vibes. Each panel featured two “live scribers” or graphic recorders — professional artists that illustrate posters depicting the panelists’ comments in a mix of images and text in real time. Imagine graduating from Rhode Island School of Design and your first gallery showing is for arms dealers in a hotel lobby.

The overwhelming sense from these visuals was (unsurprisingly) the frustration felt by founders, executives and financiers over government rules and regulations. As one CIA-turned mil-tech exec lamented on stage “I don’t like rules.” In the past, the model was for the military to determine what weapons it needed, then contract with producers to provide those systems. The participants wanted to turn that model on its head — for industry to develop its own weapons systems independently on a "commercial" basis — then sell that to the government. For the military to tell the firms what the problem is, and let the firms figure out what weapons systems to design and offer.

The problem with using this model for weapons is that commercial technologies are typically developed for a lot of buyers. Consumers don’t contract with Apple to design a laptop for them; Apple makes a range of laptops designed to appeal to millions of consumers who can choose to buy them (or not). But if there’s only one Pentagon – who’s going to be buying all the other weapons?

The answer to that question is (apparently) the rest of the entire world. The attendees emphasized the need to “design for exportability” from the beginning by re-writing the rules to get requirements from potential foreign customers before the design process begins, through soliciting “problem statements” from clients instead of detailed specs. But doing this requires huge overhauls to the way the U.S. has traditionally sold its huge catalog of weapons systems.

According to the panelists this new model requires building a “global industrial base” where U.S. weapons systems could be manufactured and assembled at a network of sites across the globe. The first step would be expanding the current AUKUS ITAR exemption, which allows for the free movement of weapons, technologies, services, and personnel between the U.S., UK and Australia without going through the (already imperfect) approval process.

Secondly, and more permanently, these industry reps also want the traditional government-to-government FMS system to operate more like the direct commercial sales (DCS) process, which is often a cheaper and faster route for foreign buyers, allowing firms to ‘move fast and sell more things’ (to borrow from a popular Silicon Valley idiom).

The implicit observation underlying these discussions about modifying procurement rules is the expectation of rising tensions all over the globe, driven by regional hegemons fighting it out in their spheres of influence, greasing the wheels with features like just-in-time production and the kind of distributed supply chains you see in the garment industry.

The visions of these CEOs for the future of the MIC in many ways mimics what we’ve seen in other sectors. In addition to outsourcing as much production as possible, there was an emphasis on removing human labor to the greatest extent possible with automated factories. Executives said we need mass unmanned attritable (i.e, disposable) systems rather than “exquisite manned platforms.” So not only would a lot of this be assembled outside the US, it would also be assembled by robots, and then operated by them too.

The old approach of the legacy contractors – pushing narratives about the U.S. jobs their products generate — is going to be a harder sell the longer these guys keep talking.

Like fast fashion for fighter jets, except instead of getting jeans that disintegrate in the washing machine you get weapons that have to be replaced more frequently, which of course means more money for producers. There are startups, investor groups, and financial firms whose sole purpose is to drive the US to spend more money on military-tech – and they use the same revolving door model employed by the old guard.

DEFCON AI, for example, develops software simulations to “streamline procurement for U.S. government agencies and contractors” and is headed by Yisroel Brumer, the former Acting Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation at DOD. The firm’s main VC funder Red Cell Partners, counts former Secretary of Defense Mark Esper as both a board member and a managing partner.

Govini is another example; the firm claims to replace “manual” acquisition decisions with AI software models to speed up procurement, and it recently landed a nearly $1 billion Pentagon contract. Financial firms like Leonid Capital — which also includes a number of military veterans among its executives — are providing novel funding mechanisms to get more military tech startups into the Pentagon’s supply chain. It’s not so much that the fox is in the hen house as the fox drew up the henhouse blueprints and aimed the chicken run right into his den.

These industry and financier-driven demands are already being implemented Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, who is stripping oversight, review, and compliance capacity from government agencies in favor of “portfolio-driven” assessments that will allow foreign customers to design and fund weapons projects up front.

A common refrain from panelists was the urgency to develop weapons without the direct influence or guidance of the U.S. government. After all (according to them) this is what Palantir did. If seed funding, privileged contracts, and “forward-deployed engineers” working directly in CIA offices to shape the company’s software don’t count as influence I’m not sure what would. The level of vocal disgust the attendees had for the U.S. state was deeply ironic given that many (if not most) of them are deeply reliant on it for the salaries, subsidies, and bailouts that fund their pensions, startups and investment funds.

Although united in their shared goal of asset stripping the U.S. government, the tenor from the investors this time around seemed a little muted — and not just during the impromptu 9/11 and Charlie Kirk remembrances. Although one guy expressed an eagerness to “get some of those Hizbullah pagers” the halcyon days of the initial AI-boom have been somewhat overshadowed by a wave of AI data center cancellations, massive post-2022 layoffs in Silicon Valley, and tech execs selling off their own stock.

One got the sense that for many attendees this was less of a scouting operation and more of a class reunion. One attendee from Black Rock, the world's largest asset management firm, about six beers deep and sporting a huge barbecue sauce stain on his oxford button up, was less interested in surveying industry trends than querying fellow attendees about the newest UFO video released in a House Committee hearing the day before.

To be sure, the new methods and aesthetic of the tech oligarch-inflected MIC are different. When they talk about war-driven profits they sound more like Friedrich Nietzsche than Viktor Bout. But fundamentally it’s still the same parasitic ruling class, fashioning themselves as builders of prosperity, rather than vultures picking clean the carcass of America’s economy.

- Tech billionaires behind Greenland bid want to build 'freedom cities' ›

- Tech bros go to Washington: Coders want in on the kill chain ›