Despite what the Pentagon leaks suggest and a real sour note from the top U.S. diplomat as recently as this fall — threatening to protract the conflict even further — it looks like there may be hope for all sides to end the Yemen war after all.

It began on April 9 when for the first time since Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates amassed a coalition to suppress Ansar Allah’s ascent to power more than eight years ago, a Saudi delegation arrived in Yemen’s capital Sana’a to negotiate directly with the group, also known as Houthis.

This event — captured by a handshake between Yemen’s Mahdi al-Mashat and Saudi’s Mohammed al-Jaber —marked a dramatic shift in the long asymmetrical war and blockade that has killed over 375,000 Yemenis and starved millions more.

April’s talks have proceeded successfully by most measures, with Saudi pledges to lift the blockade, prospects for civil wages to be paid, and a dramatic prisoner exchange over the weekend.

Last month, China played an important role in negotiating a rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran. While China’s negotiations have had positive effects between rivals in the region, Oman’s role in brokering peace talks between Saudi Arabia and Yemen should not be understated nor conflated with China’s efforts. Still, neither country participated in the war on Yemen or other recent conflicts in the region, which positions them as credible peace brokers.

On the other hand, the United States’ military involvement in Yemen through three administrations over the past eight years placed them firmly in the role of warmakers.

In March, Biden’s envoy to Yemen Tim Lenderking traveled to Saudi Arabia and Oman while Biden’s national security adviser Jake Sullivan spoke to the war’s architect, Mohammed bin Salman, and “welcomed Saudi Arabia’s extraordinary efforts” of a roadmap for ending the war. While these efforts seem to indicate the Washington’s interest in inserting itself into the negotiations, they also remind us of whose side the U.S has been on for the last eight years.

The recent Pentagon leaks reflect some real resistance through March on behalf of the Saudis to Houthi demands regarding paying for civil salaries, and Houthis felt there was deliberate foot dragging. Recall that Lenderking publicly denounced the proposed concessions as “maximalist and impossible demands that the parties simply could not reach” in October. The Saudis finally assenting to these demands (and more) reveals both their desperation to exit a war they could not win, and the Biden Administration's increasingly ineffectual and in many ways counterproductive role in the process.

The fragile road toward peace between Saudi Arabia and Yemen’s Ansar Allah is beginning to materialize, which could pave the way to further diplomatic efforts to end the war.

Background

The war’s origins can be traced to the popular uprisings in 2011 in which Yemenis sought to oust their longtime dictator, Ali Abdullah Saleh. After agreeing to transfer power to his longtime Vice President, Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi, the country was on the brink of chaos as various factions sought to be represented in Yemen’s new government. This came to a startling conclusion when the Houthis seized the capital and forced Hadi into house arrest. Despite this turmoil, Jamal Benomar, the United Nations Special Envoy for Yemen, was able to broker a deal among all Yemeni factions that “cover[ed] the shape of the executive and legislature, security arrangements and a timetable for transition.”

Two days later, without warning, Saudi Arabia began its military bombardment and occupation of Yemen, ostensibly to reinstate Hadi to power.

U.S. Footprints

Since the early moments of the conflict, President Obama was quick to declare his administration’s support of their Saudi allies. Immediately following the derailment of Yemenis’ consensus government, a White House statement announced the establishment of a “Joint Planning Cell” and ironically warned that “a legitimate political transition” can be “accomplished only through political negotiations and a consensus agreement among all of the parties” –i.e., precisely what they just derailed.

In the years that followed, Presidents Obama and Trump provided “at least $54.6 billion of military support to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) from fiscal years 2015 through 2021” according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). And while President Biden claimed to end “offensive” support for the war in early 2021, the GAO report found that a distinction between “offensive” and “defensive” operations was never delineated by State officials (p. 24), and military support to the coalition continued to be provided by the third, and current, U.S. administration since the war began.

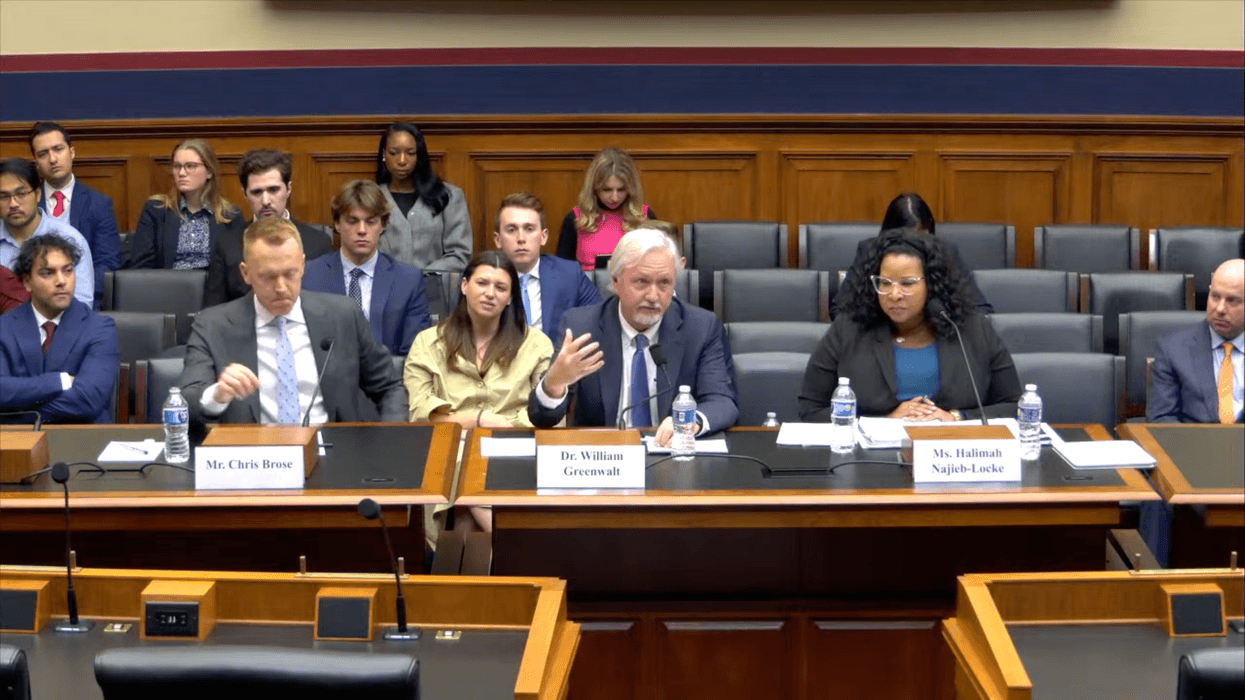

Military support for the war went far beyond weapon sales. Over the years, the U.S. provided logistical support, chose targets from the command room, shared intelligence, fueled jets mid-air, trained Saudi and UAE pilots and ground forces, provided spare parts, maintained equipment and aircraft, provided diplomatic cover for the war and blockade, and even secretly deployed U.S. Special Forces, or the Green Berets, to the Saudi-Yemen border. This amounted to an illegal, unconstitutional war that implicated the U.S. as party to the war and prompted Congress to pass its first War Powers Resolution in April, 2019.

Congress tried and failed last year to end U.S. participation in the war due to Biden’s opposition to a Senate resolution that would have withdrawn U.S. support for Saudi Arabia, arguing that it would “complicate” diplomatic efforts, presumably because it would take away Saudi leverage over Houthis in ongoing talks. Yet, this position ignores the U.S.’s own role in the war, which has been described by a UN report as likely being complicit in war crimes.

Criteria for a Lasting Peace

As the Saudis and Ansar Allah promise to continue talks following the initial breakthroughs they made last week, a lasting peace would have to include cessation of all foreign intervention and backing of local actors. This includes the UAE’s arming of the secessionist Southern Transitional Council, Saudi’s backing of the Islah Party, and the U.S.’s backing of the Saudi-led coalition.

The roadmap would also have to ensure Yemen’s sovereignty is restored by lifting the blockade entirely, and ending the UAE’s occupation of areas such as the island of Socotra and Saudi’s occupation of Al-Mahra province. This exit could then set the stage for peace among Yemenis, who have a vested interest in coexisting and are more than capable of reaching a negotiated settlement.

After all, these same groups once reached a deal in the Spring of 2015, before Saudi, the UAE, the U.S., and others in the so-called international “community” waged a war and blockade so devastating, it turned Yemen into the world’s worst humanitarian crisis of the era.