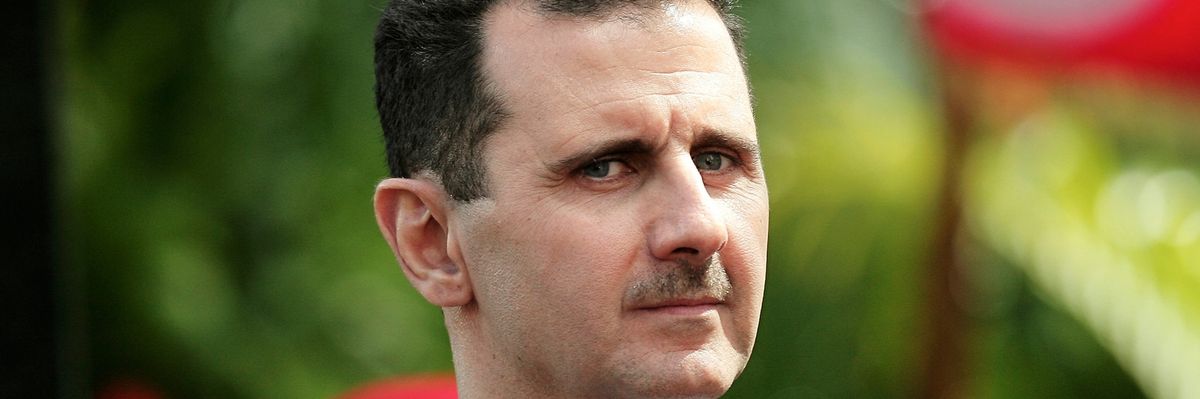

President Bashar al-Assad winning last month’s “puppet show” election with 95 percent of the vote surprised no one with any basic understanding of how Syria’s regime functions. But it serves an important purpose for Assad’s government in Damascus: he wants to convey that he is not only popular, but that his regime has emerged victorious from the Syrian civil war and a new, post-conflict era is just beginning.

“The festival of pro-Assad fealty and the one-sided political celebrations have both domestic and regional connotations,” Danny Makki, a Damascus-based analyst, told Responsible Statecraft. “Firstly, it shows who is still the boss in Syria and secondly it is a not-so-veiled message to the Gulf states who are half-way through a slow rapprochement with Damascus, it is a clear signal to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates saying, ‘Look at who is in charge here, deny my popularity now.’”

An economy in shambles and U.S. sanctions

Although the regime is celebrating its victory over the Syrian opposition, the country’s future during Assad’s fourth seven-year term looks bleak.

“Syria's economy is a shambles, the currency has collapsed, there is limited electricity in all parts of the country, and Syrians have never felt more hopeless and poor,” explained Dr. Joshua Landis, a non-resident fellow at the Quincy Institute who teaches Middle East studies at the University of Oklahoma. “Assad's overriding concern is to jumpstart the economy and to rebuild the coalition of political forces that has kept his family in power for 50 years. He must at the very least convince Syrians to submit to his rule. He will also try to rebuild a modicum of trust among the elites he depends on to rebuild the country.”

Although this election may help the Damascus regime’s standing in the wider Arab world, it will do nothing to legitimize Assad with western governments. Application of the Caesar Act is one initiative where there is continuity between the Trump administration and Biden’s. Having taken effect in 2020, the Act authorizes sanctions to be imposed against any company or individual -- U.S.- or foreign-based -- that does business with the Syrian economy’s most important sectors. Its extraterritorial reach will exert a chilling effect on potential foreign investors or other commercial enterprises that may be otherwise inclined to take part in Syria’s reconstruction.

Assad and his most powerful foreign ally, Russia, are nonetheless hoping to convince wealthy Gulf states to finance Syria’s reconstruction and development and that the just-concluded election, as farcical as it was, will help in that effort. With renewed relations with former adversaries Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, and tentative outreach by Saudi Arabia, Assad’s Syria may soon be readmitted to the Arab League.

Lacking a broad and realistic strategy for Syria

At this point, the Biden administration lacks a clear or coherent strategy for dealing with Syria. The White House may conclude that a relatively “hands-off approach” is “strategically tenable.” As Steven A. Cook at the Council on Foreign Relations recently opined, “There is not enough at stake in terms of U.S. interests for the United States to do much more than sanction, strike at terrorists, and protest Assad’s many transgressions against his fellow humans in the hope that something will change that brings an end to Syria’s nightmare.”

Even if based on wishful thinking, the Biden administration may see aggressive enforcement of the Caesar Act as leverage to force Assad to make long-sought concessions to the West, including some form of power-sharing with the opposition and reducing Moscow’s and Tehran’s influence.

Regarding Idlib, which remains under the control of Islamist insurgents, the administration will probably work closely with Ankara. “Turkey has begun to provide numerous services and to replace Damascus as the North star of their loyalty and money,” noted Landis in an email exchange. “As Hatay was folded into Turkey after its annexation in 1939, the North-West of Syria could also become part of Turkey if the international community allows it. Many of the inhabitants of both regions would accept to become Turkish rather than return to a Syria run by Assad.”

At the same time, the White House wants to ensure that U.S. military forces maintain their presence in the relatively hydrocarbon-rich northeast in cooperation with the Kurdish-dominated Peoples’ Protection Units, or YPG, even if such a policy will exacerbate ongoing tensions with Ankara. Last year, before he was confirmed as Biden’s secretary of state, Antony Blinken stressed that the U.S. military role in the Kurdish-ruled enclave gives Washington a valuable “point of leverage” vis-à-vis developments elsewhere in Syria. Landis, however, believes that the Assad government will eventually retake northeastern Syria as Washington will “tire of its effort to use Rojava, the Kurdish name for the region, as a battering ram against Assad and Iran.” The YPG “will come to terms with Assad, as painful as they will be,” given that the group would rather live under Assad than face the Turks once it ceases to have Washington to depend on, according to Landis.

Countering Russia and Iran in Syria?

The administration will, however, seek to counter Russian and Iranian influence in Syria, particularly in light of concerns by Israel — which has carried out numerous attacks on Iranian or Iranian-backed forces with Washington’s apparent approval in the last few years — about the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ presence and its support for various Shite militias there. Within this context, Washington will likely strike Iranian-backed militias, such as Kata’ib Hezbollah, Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada, and the Fatemiyoun Brigade.

In determining Biden’s policy, much will depend on how, if at all, the administration relates to the Astana Process. It was launched in 2017 by Russia, Iran, and Turkey with the aim of deescalating the Syrian conflict and eventually arriving at a political settlement which so far, however, the parties have failed to achieve.

Astana has enabled Moscow, Assad’s most powerful backer, to deepen the Syrian opposition’s divisions and helped it draw Turkey more closely into its orbit. Perhaps most importantly, by working with Iran and Turkey, the Russians have been able to reduce Washington’s influence.

Astana’s failure to date to resolve the most sensitive questions of the 10-year-old civil war, such as Assad’s future and a new constitution, raises the question of whether Washington still has a strong hand to play and to what end. Landis is skeptical. “The U.S. is likely to progressively lose interest in tipping the scales of power within Syria, especially as it discovers how difficult and expensive it will be to turn Northeast Syria into a viable economy, not to mention how thankless will be the task of adjudicating between Arabs and Kurds as well as Turks and Kurds,” he told Responsible Statecraft.

Biden’s team, which is unlikely to change Washington’s long-standing view that Syria’s head of state is illegitimate, will seek to prevent Assad from asserting more control over the population and reestablishing trust among Syrian elites whom the president will need to rebuild the country, an undertaking which, according to a 2019 United Nations estimate, will cost as much as $250 billion.

That sum will also clearly require substantial foreign aid and investment much of which Moscow and Damascus hope will be provided by the oil-rich monarchies of the Persian Gulf.

As Landis put it, “The faster that neighboring states reestablish relations with Syria and begin to undercut Western sanctions, the faster Syria's economy will begin to grow again, and the faster reconstruction will take place.”

But that is also where the Caesar Act and how the administration decides to use it can play a critical role. While it has not yet resisted the growing trend by Arab governments to reestablish formal diplomatic relations with Damascus — a mostly symbolic move — the administration at this point can be expected to use the Caesar Act as a threat to discourage any major renewal by the Gulf countries of strong economic ties and investment in Syria. Indeed, the UAE’s foreign minister, Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan, alongside his Russian counterpart in Dubai in March, said the sanctions “make the matter difficult” regarding international cooperation on the Syria file.

At the same time, the Gulf monarchies will likely argue that their economic engagement with cash-strapped Damascus, as with Baghdad, would increase their own influence with Assad at Iran’s expense. Whether this carries any weight in Washington has yet to be seriously tested.

Focused primarily on its domestic agenda and on Iran and Yemen in the Middle East, however, the Biden administration seems to be content with putting Syria on a back burner with the Caesar pilot light turned on.

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org