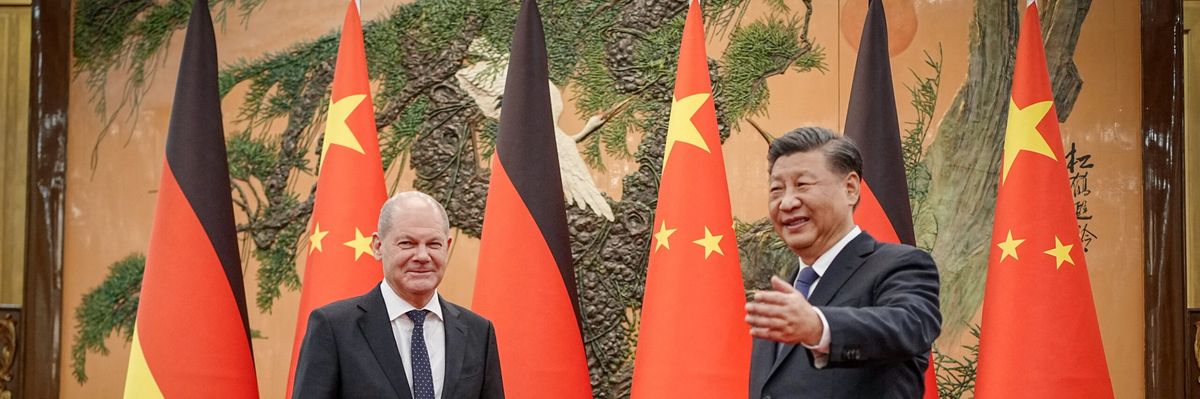

The visit to Beijing by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz this week has produced modest but real diplomatic results. Chinese leader Xi Jinping issued a strong statement warning all countries not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons — something that can be read above all as a warning to Moscow not to use them in Ukraine.

Xi also called for urgent negotiations to end the conflict in Ukraine, without however accompanying this with any language condemning America and NATO or supporting Russia. Scholz for his part condemned Chinese human rights abuses and called on the Chinese government to use its influence with Moscow to end the war in Ukraine. In an article written before the visit, Scholz pointed out that Germany’s trade relationship with China is a reciprocal one, but also pledged to reduce German dependency in certain areas. He stated German opposition to any moves for Chinese hegemony; but in what looks like a warning to Washington, he also stressed that “Germany has no interest in seeing new blocs emerge in the world.”

Scholz’s visit has attracted fierce criticism from politicians and the media in the U.S., Europe and Germany itself, including tediously predictable titles like “Scholz Kowtows to Beijing.” Despite Scholz’s emphasis that continued cooperation with China is essential to the struggle to limit climate change, Annalena Baerbock, the German Foreign Minister and leader of the Green Party in the governing coalition, has declared that:

"We can't afford to just hope that things won't be so bad after all with these autocratic regimes…It is important to the German government and to me personally that we transfer what we have learned from our dependence on Russia to our new China strategy,"

Xi’s statement on Ukraine was probably as much as could realistically have been hoped for. Those Western politicians and commentators who have called for China to join Western sanctions against Russia are being foolish. Even India, a U.S. partner and fellow democracy, has not done so. Nor has most of the world. For both geopolitical and economic reasons (including partial dependence on Russia for China’s energy security), there was never a chance that China would join in a U.S.-led economic war against Russia.

But if those Westerners who said they hoped for Chinese partnership with the West against Russia were being naively optimistic (or simply looking for another stick with which to beat China), those who talk of a Sino-Russian “alliance,” are guilty of gross exaggeration, and a careless and dangerous misuse of the term “alliance” —though they have some excuse in the fact that Chinese and Russian rhetoric has also talked in these terms.

There is indeed a Sino-Russian partnership; but there is no alliance. China will not fight for Russia in Ukraine any more than Russia will fight for China in the Far East. And if China has not joined the West in economic pressure against Russia, it has also given virtually no military or economic help to Russia, beyond — like most of the world — going on buying Russian oil and gas.

This restraint is somewhat surprising. Given the growing hostility between the United States and China, and the warnings of possible war over Taiwan from analysts on both sides, one might have expected the Chinese government to do everything in its power to strengthen Russia against the United States; especially since Russia is almost the only powerful strategic partner that China possesses.

The explanation for China’s failure to help Russia lies partly in an ongoing Chinese tendency to strategic caution, which (outside the South and East China Seas) remains far greater than most Western commentary acknowledges. Chinese restraint is also however due to fear in Beijing that military and economic aid to Russia would lead the European Union to join the United States in imposing very damaging economic sanctions on China.

Clearly however this cuts both ways: If China is refraining from helping Russia’s war in Ukraine because it wishes to keep good economic relations with Europe, then if Germany and Europe radically reduce economic ties to China under U.S. pressure, Chinese aid to Russia is likely to increase proportionately.

Criticism of Scholz’s visit to China was increased by his recent decision to allow COSCO, a Chinese shipping corporation to buy a 25 percent stake in a port terminal at Hamburg, despite strong opposition from Washington and his own coalition partners. Scholz’s decision was no doubt due in part to a desire to help the city of Hamburg, of which he used to be the Mayor.

The Chinese stake was however reduced from the original share of 35 percent, and a share in one terminal will not bring China anywhere near controlling Hamburg docks. If China is to be barred from buying even a minority share in European infrastructure projects, then Europe will indeed be well on the way to economic decoupling from China. Moreover, while Germany has serious concerns about unfair trading practices and theft of intellectual property by China, a strong element of reciprocity does exist. BASF, the German chemicals company, is building its third largest plant in China. BMW is setting up a new company in China — in both cases, wholly German-owned.

Foremost in Scholz’s mind however is the harm that such a decoupling would cause to the German economy and the industrial trades unions that are still a vital part of the Social Democratic Party base. Scholz was accompanied to Beijing by the leaders of Germany’s largest industrial enterprises, and German industry has been strongly supportive of his visit.

Like his fellow Christian Democrat and predecessor,Chancellor Angela Merkel, Scholz is clearly determined to protect Germany’s high-tech industrial base — something to which the Greens and Liberals seem to have become strangely indifferent. Scholz’s desire to hold onto Germany’s markets in China has been increased still further by the risk of great damage to German industry from the reduction of Russian gas supplies.

Since 2016, China has been Germany’s largest trading partner, with $242 billion in trade in 2021 — an increase of 15 percent over the previous year. Germany’s exports are overwhelmingly in the areas of sophisticated and high-value manufactures: vehicles, machinery and electronic equipment account for more than three quarters of the total. The Chinese market is especially critical for German carmakers, accounting for 40 percent of Volkswagen’s global sales so far this year. Access to China’s steeply growing market for electric vehicles is seen as of critical importance to this branch of German industry.

As already noted in Responsible Statecraft, the implications of a steep and rapid decline of German industry would go far beyond the economic. The result would almost certainly be a surge in support for radical parties of the Right and the Left, threatening the viability of German democracy.

This is a danger to which the U.S. establishment should be paying far more attention. For despite sporadic attempts at political manipulation, the external threat to Western democracy from Russia and China is in fact minimal, and has diminished still further in recent months. The Russian military’s combination of brutality, demoralization and incompetence in Ukraine is hardly an advertisement for the Russian system.

Nor is there much appeal in the Putin regime’s increasing repression at home, and China’s increasing move from authoritarianism back to totalitarianism. The causes of political polarization and democratic decline in the West are overwhelmingly domestic, and cannot be seriously addressed by confrontation with Russia and China.

Insofar as the Biden administration claims that the defense of democracy throughout the world is at the heart of its national security strategy, it should be concerned with the economic wellbeing of key allies at least as much as it is with confronting China — perhaps much more.